The Forest Rights Act (FRA), which was passed by Parliament in 2006, could fundamentally change the lives of adivasis and other forest-dwelling communities who are dependent on forests for their livelihood and are considered to be at the bottom of our social hierarchy.

The Act clearly mentions that it is being enacted to remove the historical injustice done to forest dwellers. Its enactment not only gives a legal imprint to the traditional rights of forest dwellers but also has the potential to achieve the objectives of social justice, decentralisation of power, and forest conservation through community participation.

The Act could, finally, help restore the self-esteem that the system has long denied adivasis. The political leadership of the time deserves credit for enacting this progressive law.

Legal Framework

The Act recognises five types of rights.

(i) Individual forest rights (IFR): Land for habitation and cultivation up to four hectares; Scheduled Tribes must have occupancy before 13 December 2005; other traditional forest dwellers (OTFD) require 75 years of proof.

(ii) Community rights (CR): Rights to collect, process, and sell non-timber forest products such as bamboo, honey, tendu leaves, and so on to community members.

(iii) Community forest resource rights (CFRR): Rights of gram sabhas (village assemblies) to protect, regenerate, and manage forests sustainably.

(iv) Habitation rights: Traditional habitation and grazing rights of particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs), nomads, and pastoralists.

(v) Cultural and religious rights: Protection of sacred sites and traditional religious practices.

The use of these rights is subject to certain restrictions, including a prohibition on selling the land, a bar on commercial exploitation, and a responsibility to ensure the sustainable use of forest resources.

The Act identifies the gram sabha, made up of all voters in small settlements such as villages and hamlets, as the most important decision-making body. Gram sabhas receive individual claims to forest rights, formulate and verify community claims, and approve them before forwarding approved claims to sub-divisional and district-level committees for further verification and final approval. Gram sabhas remain accountable for all the rights and responsibilities granted to them under the Act, including how the recognised forest rights are used in practice.

Progress Achieved

According to the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2023, India has 715,343 square kilometres of forests; which is equivalent to 71,534,300 hectares or 21.76% of the country’s total area.

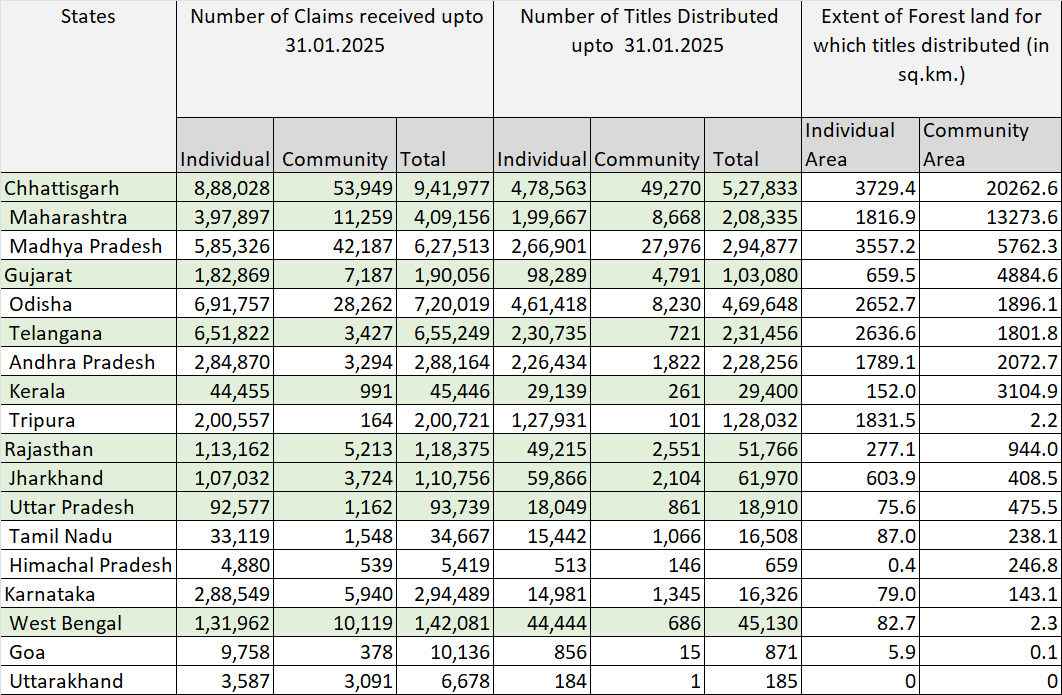

Table 1 gives the progress made in the implementation of the Act as on 31 January 2025, according to the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India

Table 1: State-wise Claims and Grants of Titles under the FRA (until January 2025)

When the two highest performing states are compared, the average community land allotted per gram sabha in Chhattisgarh (49,270 gram sabhas) is 0.411 sq km. In Maharashtra (8,668 gram sabhas), the average is 1.53 sq km, which is about 3.7 times the average in Chhattisgarh.

Under the Act, the gram sabha has the right to protect, regenerate, and manage community forest resources for sustainable use. This enables gram sabhas to explore various ways of generating income and creating livelihood opportunities. There are several examples in Maharashtra, especially in Gadchiroli district, where gram sabhas have used these rights to achieve significant progress and self-development.

However, even after 18 years of this law being in force, similar change is not visible in many other forest areas of India. This gap calls for serious introspection.

Major Implementation Issues

(i) Lack of awareness and language barrier: One of the key problems in implementation is the lack of awareness, or only an incomplete understanding, among forest dwellers about their rights. Only in a few places in Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha, where there is active local leadership and sustained efforts by voluntary organisations to create awareness, considerable progress has been achieved.

One of the authors had a revealing personal experience in a remote region of Gadchiroli district. The government of Maharashtra had carried out a campaign to grant community forest rights, but the titles were distributed without involving local people in the process, and without any training or awareness-building.

As a result, the beneficiaries did not understand what difference these legal forest rights made to their lives or how their ownership of titles had affected the authority of the forest department. The title papers were simply kept at home among other miscellaneous documents, with little understanding of their significance.

Instead of mechanically conducting mass campaigns, it would therefore be more appropriate to educate and sensitise people about the meaning and importance of forest rights. One major obstacle in this process is language. All government proceedings are conducted in the official language of the state, which is often different from the languages that forest dwellers actually speak, making it difficult for them to grasp the meaning and provisions of the law.

In this context, a positive initiative called the “Ekal Project” is underway in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra. With the help of Gondwana University, Gadchiroli, the district administration has formed teams of local youth trainers who conduct awareness and capacity-building programmes in various gram sabhas. Such an initiative should be replicated in other places as well.

(ii) Administrative and bureaucratic hurdles: Forest department officials often remain sceptical about granting individual forest rights. They argue that these provisions have encouraged some forest dwellers to keep cutting trees and then file claims under the Act, and they frequently cite a few isolated incidents as “evidence” for this view.

In many districts, especially in remote areas, implementation of the law faces serious hurdles such as a shortage of trained personnel and a lack of technical expertise needed for proper surveys. Misinterpretation of the provisions of the law leads to anomalies, for example, approving individual forest rights for much smaller areas than those claimed, or granting forest land located at a distance instead of the traditional forest area that has actually been claimed.

In many states, forest department officials who sit on verification committees frequently cite provisions of the Forest (Conservation) Act to reject claims or to keep them pending without any decision. This practice violates the Forest Rights Act, which is meant to prioritise the recognition of forest dwellers’ rights.

There is a constant ideological tension between a traditional conservation approach, which resists human presence in forests, and the perspective of the Forest Rights Act, which integrates forest dwellers into conservation and management. This tension reflects a deeper mindset framed as “conservation versus forest rights”.

Areas are often declared protected or notified as wildlife habitats without adequately considering the provisions of the Forest Rights Act. Some conservation enthusiasts still believe that the Act harms biodiversity conservation, even though many gram sabhas that have obtained forest rights are effectively managing and conserving forests within their boundaries. It is truly unfortunate that such misconceptions persist despite these positive examples.

(iii) Delay in deciding claims: According to data from the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, as of 31 May 2025, even in states like Chhattisgarh, around 15–18% of claims, and in Maharashtra nearly 22% of claims, have not yet been settled, even though these two states are considered to be ahead in implementing the law. In many other states, among the claims that have been decided, the proportion of rejected claims is even higher. Although the three-tier system for approving claims is sound in principle, in practice there are significant delays, with claims often kept pending at different stages of the process, sometimes for years.

Many forest dwellers, especially those belonging to particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs), do not have records to prove their long-term habitation in forests. For other traditional forest dwellers, too, it is often difficult to produce evidence of land cultivation over three generations (75 years). In both cases, oral testimony from elderly persons is not always accepted as valid proof.

Satellite images, which could provide concrete evidence of land cultivation over the past 75 years, are not always available, and even when available, they are not consistently used in the verification process. Government records that could support such claims are also often inaccessible to the claimants.

Some voluntary organisations are trying to address these gaps by networking gram sabhas that have successfully secured claims with those that are still struggling to have their claims settled.

(iv) Misunderstanding and misinformation: In some places, there is also a lack of clarity about the relationship between the Forest Rights Act, 2006 and laws such as the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and the provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA). This confusion is an important reason why many claims under the Forest Rights Act are rejected.

(v) Difficulties in the gram sabha: The gram sabha is the main decision-making body in implementing this law, from the initial approval of claims to the actual granting of forest rights. However, gram sabhas face many difficulties in carrying out this practical work.

In many cases, because of limited information, gram sabhas have to depend on external help, which can make them vulnerable to outside pressures. In remote areas, a lack of awareness or the absence of a quorum, especially during the agricultural season, often makes it difficult to hold meetings.

The technical aspects of forest rights verification are often difficult for gram sabha members to understand because they have limited knowledge or lack training. They struggle with using maps, fixing boundaries with GPS (Global Positioning System) devices, understanding legal terms and phrases, and properly documenting community claims.

The adivasi communities are not homogeneous. Even among other traditional forest dwellers, caste hierarchies exist. As a result, groups form within the gram sabha, and the more dominant group usually takes the lead. Since different groups have different priorities in the use of forest resources, there is a feeling that some sections do not get justice when decisions are taken, although there are also examples where such mixed communities have made wise decisions and achieved good results.

Even though women play an important role in forest-dependent livelihoods, gender discrimination means that their opinions are often not given importance in decision-making. Ensuring women’s meaningful participation in gram sabha meetings therefore remains a major challenge.

(vi) Coordination between government departments: Coordination between the tribal affairs department, forest department, and revenue department is very important for effective implementation of forest rights.

The forest department is responsible for protecting timber and wildlife in areas with community forest rights and for maintaining consolidated records of all forest produce from these areas. For this reason, it often opposes relinquishing control over these areas. For example, in many places it is not willing to give up control over the felling and sale of bamboo and tendu leaves, and disputes over who has the authority to issue transport permits for bamboo are a constant irritant.

Gram sabhas with community forest rights are required to prepare a “Conservation and Management Plan” for managing the forest area allotted to them. This plan should include proposals for forest management activities, and some proposed works may involve more than one government department, in which case collaborative implementation is needed.

In view of this, Maharashtra decided to establish “convergence committees” (samnvay samitis) at the district level, chaired by the district collector. These committees include all district-level officials involved in development work. All plans submitted by gram sabhas are reviewed by the convergence committee, which then assigns different responsibilities to the relevant departments.

(vii) Demarcation of Boundaries: There are often technical difficulties in accurately determining the boundaries of the claimed areas using cadastral maps or GPS devices in many community forest resource rights areas, which cover large and complex terrain. Differences may arise between the boundaries agreed upon by the members of the gram sabha and those marked by the forest department, and for this reason claims are sometimes approved for smaller areas than those claimed or are rejected altogether.

To overcome these problems, flexible policies for recognising evidence are required. This includes accepting the oral testimony of elderly people, decisions of the community on boundaries, and traditional boundary markers. Special provisions are necessary for particularly vulnerable tribal groups and for forest dwellers in remote regions so that their forms of evidence can be accepted.

Recently, there has been experimental use of more accurate GPS technology in Gadchiroli district. If successful, this technology could help resolve many local boundary-related issues.

(viii) Pressures of Projects: Often, large reserves of minerals and other raw materials needed by industries are found in forest areas. As a result, industrial interests keep a close watch on these areas, which creates pressure to bypass the provisions for granting forest rights to adivasis. In many cases, forests are converted to non-forest land for development projects in violation of the Forest Rights Act, without completing the legal requirements.

For example, approval is given for activities such as afforestation, wildlife habitat projects, mining leases, or infrastructure projects like roads and railways in areas where community claims are still unresolved. Even in forest areas where rights have already been granted, the provisions of the law are violated.

The case involving Odisha Mining Corporation and Vedanta Resources Ltd/Sterlite Industries in the Niyamgiri Hills in Odisha is well known. In Maharashtra, projects such as the Lloyd Steel (Lloyd Metals and Energy) mine in Surjagad, Gadchiroli, and projects in the Zendepar area are regularly in the news for similar reasons, with allegations that they have violated various provisions of the Forest Rights Act.

Recently, Maharashtra’s revenue minister publicly announced the government’s intention to introduce a law allowing tribal farmers to lease their land to private entities for agriculture or mineral excavation, including in districts such as Gadchiroli. News reports on this proposal have appeared in several outlets, including The New Indian Express, Business Standard, and the Hindustan Times. In protest against this move, forest dwellers in Gadchiroli district launched an agitation.

Way Forward

The Forest Rights Act has the potential to enable forest management through public participation combined with scientific methods. For this to happen, government departments—especially the forest department—need to change their traditional outlook. Going forward, the forest department needs a perspective that includes not only the “conservation and development of forest areas” but also the “development of forest-dwelling communities”. This means treating the well-being and progress of forest dwellers as a central part of forest conservation policy so that the overall approach becomes more inclusive and sustainable.

The implementation of the Forest Rights Act should not be seen merely as the formal recognition of rights. It should be treated as a means to achieve sustainable forest management, including sustainable harvesting of forest produce, adding value to non-timber forest produce, and developing strategies for marketing these products.

In Maharashtra, a minimum support price has been declared for some forest produce. As a guarantee of receiving the minimum support price, the Van Dhan Yojana is an important government initiative. It supports tribal gatherers of minor forest produce by organising them into Van Dhan Vikas Kendras for value addition, branding, and marketing, thereby improving their incomes. Similar efforts are underway in other regions.

Traditional conservation knowledge should also be tested using scientific methods, and, where found effective, conservation programmes based on this knowledge should be implemented by local communities. For this, newer technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) tools, should be tried; this is not an overly ambitious proposal.

Experience in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra shows that tribal youth are quite adept at using smartphones. They routinely use applications such as GPS Logger to find locations and Google Lens to identify plant species, and, importantly, they can interact with AI tools in regional languages. Integrating scientific conservation methods with traditional wisdom under community leadership can therefore promote both rights and environmental sustainability effectively.

Evidence from states and districts where the Forest Rights Act has been implemented relatively successfully suggests that several factors are critical: strong political will, consistent administrative support, active involvement of voluntary organisations, and honest local leadership.

Weakening the Forest Rights Act

(i) The Forest Conservation Amendment Rules, 2025: Through a 2025 notification, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) increased the powers of state governments to divert forest land to infrastructure projects considered to be in the “public interest” or of “national importance”. These amended rules exempt such projects from public hearings, reduce transparency, and weaken compensatory afforestation and protective measures, thereby violating earlier orders of the Supreme Court.

(ii) Increased role of bureaucracy in gram sabhas: In mid-2025, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change and various state governments issued a joint circular directing forest officers to “assist” gram sabhas in community forest management and minor forest produce activities. This move has raised concerns that the independence granted to gram sabhas under the Forest Rights Act could be undermined and that joint forest management (JFM) committees may be brought back in practice.

(iii) Conversion of forest area to non-forest area: The Forest (Conservation and Development) Rules, 2023 and subsequent circulars have delegated to state governments the responsibility for enforcing key provisions of the Forest Rights Act, such as recognising rights and obtaining the prior consent of gram sabhas. This shift may weaken community consent mechanisms and accelerate the diversion of forest land.

(iv) Statements that undermine forest rights: In June 2025, Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav publicly made a statement suggesting that ownership rights over land granted under the Forest Rights Act are responsible for forest degradation.

(v) Redefining “forests”: The 2023 Amendment to the Forest Conservation Act has introduced a new definition of “forest” that excludes large areas of forest land from legal protection. By opening up a substantial share of India’s forests to infrastructure and industrial use, these changes weaken the principles of the Forest Rights Act and directly limit the authority of gram sabhas to approve or reject the diversion of forest land belonging to them.

Conclusions

If the Forest Rights Act, 2006 is not diluted but implemented effectively, it can align forest conservation with the development of forest-dwelling communities. Done properly, it can protect forests while improving livelihoods and safeguarding the cultural identity of these communities at the same time.

Vijay Edlabadkar (vijay.janavigyan@gmail.com) is a physicist by training and a retired college principal, and is now working with a group of tribal youth in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra.

Madhav Gadgil (madhav.gadgil@gmail.com) is an ecologist, nature lover, and a staunch believer in the good sense of people and in democratic decentralization.