The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), formerly known as Zaire from 1971 to 1977, has been engulfed in war, conflict, and devastating humanitarian crises for several decades.

The Congo has the unfortunate distinction of being colonized first by an individual rather than a state. The European powers at the 1884-85 Berlin conference awarded the Congo to King Leopold of Belgium. Initially, he plundered ivory, and when the rubber boom happened in the 1890s, he deployed concession companies to import rubber from the territory. The king’s rule in Congo became notorious for the amputation of hands of men, women, and children as an intimidation technique or as a penalty for insufficient production of rubber. In 1908, after an international outcry over the atrocities committed in the Congo, the Belgian state assumed direct control of the territory.

The country attained independence on 30 June 1960. The Congolese leadership was divided along ethnic and regional lines, with ten political parties that emerged within two years having no common vision to forge a consensus on governance, beyond seeking independence from Belgium. Patrice Lumumba, a charismatic leader of the largest nationalist party, became the first prime minister.

On 5 July 1960, Congolese troops mutinied against Belgian officers who refused to hand over command to them. Conflict broke out between the African and white populations. Belgium responded immediately, sending troops on the pretext of protecting its citizens. On 11 July 1960, Moise Tshombe, as self-proclaimed President of Katanga State, announced the independence of the mineral-rich territory. Belgium and its mining companies deployed mercenaries in support of the secessionists.

... [The Belgian] colonial construct institutionalized ethnic differences, favouring the Tutsi. In the post-colonial period, this resulted in the majority of Hutus claiming power and reversing the discrimination they faced during the colonial period.

Lumumba opposed the Belgian military intervention and its support for the Katanga secession movement. The United States and Belgium were alarmed by Lumumba’s strong nationalist approach. Lumumba appointed Colonel Joseph Désiré Mobutu as chief of the Congolese army. Convinced that Belgium was keen to destroy the unity of the government and unable to freely travel within his own country, he sought the Soviet Union’s help. The Soviet Union responded by sending military advisers and other support. In view of the prevailing Cold War tensions, the US and the West were alarmed by Lumumba’s invitation to the Soviet Union.

On 14 September 1970, General Joseph Mobutu, with the active support of the US and Belgium, seized control of the government. Mobutu arrested Lumumba and sent him to Katanga, where the Belgian mercenaries tortured and executed him on 17 January 1961. Belgium in 2002 formally apologized for its role in the killing of Lumumba.

War and Conflicts in East Congo

Hutu and Tutsi living in Rwanda and Burundi share a common language, Kinyarwanda. In Congo, the Kinyarwanda-speaking Hutus and Tutsi are known, respectively, as Banayarwandas and Banyamulenges settled in Kivu. The migration of both groups has occurred over several centuries and continues to take place. However, the Belgian authorities in the 1920s created large chiefdoms as part of the local administration, but excluded the Banyamulenge and denied them land ownership. The local population does not consider them authentic Congolese and views them as foreigners. Mobutu’s regime denied citizenship and voting rights to the Banyamulenges.

In constructing the colonial political state, the Belgian power “created” the Hutu as indigenous Bantus and the Tutsi as alien Hamites. This colonial construct institutionalized ethnic differences, favouring the Tutsi. In the post-colonial period, this resulted in the majority of Hutus claiming power and reversing the discrimination they faced during the colonial period. The Hutu quest to correct past injustice turned into revenge. The Rwandan revolution in 1959 replaced the Tutsi monarchy and established the Hutu-led republic. More than 300,000 Tutsis fled to the neighbouring countries. A group among the refugees in Uganda set up the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and, in 1990, resorted to armed incursion into Rwanda. On 6 April 1994, the plane carrying President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down over Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Hutu extremists accused the RPF of killing their president and carried out the killing of the Tutsi population across the country. In just 100 days, with the active participation of the Hutu population, the Hutu extremists killed 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

In July 1994, the killing ended with the RPF capturing Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, and Tutsi groups taking control. As a consequence, nearly two million Hutu now fled to neighbouring countries, particularly to the North and South Kivu in the Eastern Congo, bringing armed elements to an already fragile region. The former Hutu regime and its army controlled the Hutu refugee camps and mounted terror attacks against Rwanda. The genocide gave birth to the Tutsi power in Rwanda with the mission to protect the Tutsi wherever they were (Mamdani 2001).

The previously discussed citizenship question in Congo of the Banyamulenges converged and contributed to a series of wars in the Eastern Congo.

General Mobutu and the First Congo war

General Mobutu assumed absolute power in 1965 and ran a totalitarian regime, and followed the example set by the Belgian colonisers in exploiting the country’s vast natural resources for personal gain. Mobutu’s corruption was legendary, with bank accounts in Switzerland, and villas, ranches, palaces, and yachts throughout Europe. The US and the West abandoned Mobutu after the end of the Cold War.

Mobutu, following the influx of refugees after the Rwandan genocide, attacked the Congolese Tutsi (Banyamulenges) and stripped them of their Congolese citizenship. He ordered the expulsion of Banyamulenge to Rwanda. The Congolese army attacked the Banyamulenge and committed numerous abuses against them. Rwanda used it as a pretext to intervene in Congo and disarm the Hutu rebels in the refugee camps. In October 1996, the Rwandan soldiers and the Banyamulenge jointly mounted an attack against the Congolese army. Rwanda was also keen to remove Mobutu since he supported the Hutu genocidaires in the refugee camps.

Mobutu’s corruption was legendary, with bank accounts in Switzerland, and villas, ranches, palaces, and yachts throughout Europe. The US and the West abandoned Mobutu after the end of the Cold War.

Meanwhile, in October 1996, a coalition of armed movements and political organizations established the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo, also known by the French acronym AFDL. Laurent–Desire Kabila led the AFDL coalition. Rwanda played an active role in the creation of AFDL, and along with Uganda, provided arms and other support. The AFDL and its allied forces captured Kinshasa, the Congolese capital, without much resistance since Mobutu’s demoralized soldiers deserted their posts and the civilian population actively welcomed the AFDL. On 16 May 1997, Mobutu fled the country, ending his 32-year-long dictatorship. Kabila declared himself president, and the AFDL became the new national army. Human rights groups alleged that the AFDL killed as many as 60,000 civilians.

Second Congo War

President Kabila faced numerous challenges in governing the country, including having to deal with the presence of Rwandan and Ugandan forces. He expelled these armed forces, which then created tensions with his former backers. In August 1998, the Banyamulenge rebelled in Goma, which is the main city in the East. At the same time, Rwanda helped establish a Tutsi armed rebel group, the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD). The RCD took control of several towns in the East. Kabila sought the help of the Hutus in the Eastern Congo to repel the RCD and the Rwandan fighters.

The involvement of numerous African nations and at least 25 armed groups made the second Congo war one of the largest wars in African history.

Rwanda made claims to parts of Eastern Congo and accused Kabila’s government of targeting Tutsis by supporting Hutu armed groups. By mid-August, the RCD rebels captured the hydroelectric station that supplied power to Kinshasa and the diamond-producing city of Kisangani. Uganda too supported the RCD and Kabila then sought the help of other African nations.

Namibia, Zimbabwe, Angola, Sudan, and Chad backed Kabila’s government. The involvement of numerous African nations and at least 25 armed groups made the second Congo war one of the largest wars in African history. In January 2001, Kabila was assassinated allegedly by his bodyguards.. The Congolese parliament unanimously voted to swear in his son Joseph Kabila as president. On 17 December 2002, the national government, rebel groups, domestic political opposition, representatives of civil society, and representatives of major ethnic groups signed the ‘Global and All-Inclusive Agreement’. The agreement envisaged a transitional government and the conduct of elections within two years. The agreement marked the end of the Second Congo War.

2003 to the Present

In July 2003, a transitional government assumed power. The transition period included the withdrawal of Rwandan and Ugandan forces and ended in 2006, with the election of Joseph Kabila as president. The Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD ) became RCD–Goma. In 2007, the RCD–G forces became the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP). The CNDP threatened to take Goma from the government. After significant diplomatic pressure by the UN and other actors, CNDP signed a peace deal on 23 March 2009, became a political party, and its forces partially joined the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC). In 2011, Joseph Kabila was re-elected president. The CNDP failed to win any seats in the national assembly. Kabila, in an attempt to reassert the government’s control in the East, redeployed the CNDP forces, breaking the agreement with them.

CNDP's main commander, Bosco Ntaganda, led a mutiny with the support of its forces, calling themselves the M23. The name symbolically referred to the March 23 agreement that the CNDP claimed the government failed to honour. M23 commanders and rank-and-file were mainly Rwandan-origin Tutsi from Kivu. M23 justified its armed opposition to protect the Tutsi population in Kivu from the Congolese government and the Hutu armed group Forces Democratiques pour la Liberation de Rwanda (FDLR).

The UN mission in the Congo is the largest and costliest, with an annual budget of $1.1 billion. Interventions by the UN, regional, and international actors create the impression that they are doing something, but in the end, they only offer temporary solutions.

In 2013, M23 captured the key city of Goma, a vital transport hub for towns that produce metals and minerals, which was later reclaimed by the Congolese army and UN peacekeeping forces. In late 2021, M23 reemerged, capturing key towns in the East. In 2025, the M23 made gains by first capturing Goma again. It followed up by occupying Bukavu, the capital of South Kivu.

In November 2025, in Doha, the M23 and the government of Congo signed a peace framework for the east of the country. On 5 December 2025, in the presence of US President Trump, Congo and Rwanda signed a peace deal to end the more than 30-year-old conflict. The parties to Congo’s war have been involved in numerous negotiations and agreements. None of them has led to lasting peace or stability in the country. In 2000, the UN deployed a peacekeeping mission that is still present in Congo. The UN mission in the Congo is the largest and costliest, with an annual budget of $1.1 billion. Interventions by the UN, regional, and international actors create the impression that they are doing something, but in the end, they only offer temporary solutions.

The scepticism about ending the conflict in Congo stems from the fact that it is driven and sustained by several structural issues. The Cold War, which helped sustain Mobutu and his legacy, still haunts the country. The corruption and clientelism embedded in the country by Mobutu continue to contribute to dysfunctional state structures and poor delivery of services. The Congolese military (FARDC) reflects the country’s plight. It emerged after the second Congo war in an ad hoc fashion by combining units from various belligerent factions. The FARDC suffers from an overlapping chain of commands, rent-seeking behaviour, endemic indiscipline, and collaboration with non-state armed groups in the exploitation and illicit trade of minerals.

In many respects, the conflict in the east of the country is a proxy war with the involvement of many countries in Congo’s internal conflict particularly Uganda and Rwanda. Uganda’s involvement may be due to what it sees as the need to protect its border regions and managing the refugee flows into the country, but it has also benefited from Congo’s minerals, including illegal trade in diamonds.

Rwanda considers North and South Kivu falling within its sphere of interests. It claims that the Hutu armed group Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) poses a threat and therefore justifying its initial incursions into Congo. Rwanda’s intervention, directly and through proxies, is linked to its economy benefiting from regional trade in minerals from the Congo. According to a BBC report, 120 tonnes of coltan used in the production of cell phones were being sent by the M23 to Rwanda every four weeks.

A UN Panel of Experts, in its July 2025 report, concluded that Rwanda’s engagement is not about neutralizing the FDLR but about conquering additional territories. The report also stated that Rwanda’s assistance enables the M23 to expand the territories under its control, thereby providing Rwanda access to mineral-rich areas.

According to a 2024 Amnesty International report, since 1998, more than 6 million people have died, including due to hunger and disease.

Rwanda is similar to Israel in the Middle East and a darling of the West. Post – genocide minority Tutsi, who constitute 14 per cent, have been governing the 85 per cent majority Hutus since the mid-1990s. The government has been run by President Paul Kagame since 1994, when he led the Rwandan Patriotic Front and overthrew the Hutu government. To maintain the Tutsi elite's power, the government ruthlessly suppresses dissent. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) conducted a mapping exercise to document violations of human rights and international humanitarian law committed within the territory of the DRC between March 1993 and June 2003. The report included allegations that the Rwandan government’s Tutsi troops might have killed thousands of Hutu refugees in the DRC in the mid-1990s and that those crimes might have constituted genocide. In response to the report, the Rwandan government threatened to withdraw its peacekeepers from Darfur and South Sudan, and the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon stopped the publication of the report (see Ravindran 2022).

In addition to conflicts in the east, the country has witnessed numerous instances of inter-communal violence in other provinces as well. There are more than a hundred armed groups active in the country.

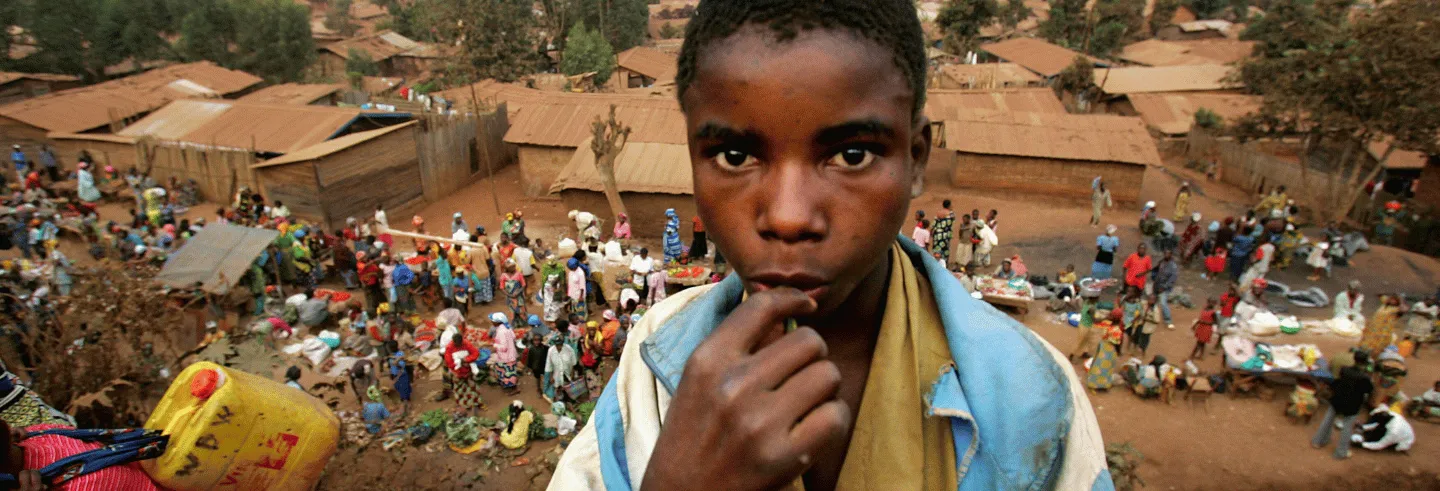

Human Tragedy

The global economy relies on minerals and metals such as cobalt, copper, zinc, tin, and gold, which has led to external groups' predatory exploitation of these minerals in Congo. Contemporary Congo wars resulting from the rush to exploit its minerals have had a devastating impact on civilians. Due to various conflicts in Congo, 7.3 million people have been internally displaced, many multiple times. Various forces fighting in Congo resort to targeted or indiscriminate killing, resulting in mass killings and injuries. According to a 2024 Amnesty International report, since 1998, more than 6 million people have died, including due to hunger and disease. The government forces and other forces routinely engage in torture, enforced disappearances, and sexual violence.

In many respects, the conflict in the east of the country is a proxy war with the involvement of many countries in Congo’s internal conflict particularly Uganda and Rwanda.

Doctors Without Borders, UK, reported that in 2023, its teams treated at least two survivors of sexual violence every hour, and the numbers increased in 2024. In December 2025, UNICEF reported that in Congo, violence against children is entrenched and rising, and it recorded more than 35,000 cases of sexual violence against children nationwide. UNICEF, in another report, stated that around 750,000 children are deprived of education in the conflict-affected provinces in the East Congo.

In addition to the human cost, the conflict's impact on the environment is horrendous. The war resulted in a loss of 1.3 per cent of Congo's forests, an area similar in size to Belgium. It is mainly due to illegal charcoal and timber trade carried out by different armed actors. During the First and Second Congo Wars, the Congolese and Rwandan armies used the Virunga National Park, Africa’s oldest national park, which was declared an endangered World Heritage Site.

Adam Hochschild’s 2002 book King Leopold’s Ghost captures the plundering of ivory, rubber, and other resources, as well as the cruelty inflicted on the Congolese. It is a different type of plunder now. Congo is still haunted by Leopold’s Ghost.

DJ Ravindran was earlier the Director of Human Rights in Peace Keeping Operations in Libya, Sudan and Timor Leste (East Timor) and has worked in post-conflict situations including Cambodia and Uganda. He is presently a member of the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries as a means of violating human rights and impeding the right of people to self-determination.

Views expressed are made in personal capacity.