Muslim political representation is one of the most insufficiently analysed questions of our public life.

Popular and scholarly work employ a mechanical formula to quantify Muslim representation. 1Iqbal Ansari's two-decade-old work (2006), which used this method extensively, is accepted as a model to reestablish Ansari’s findings. A new generation of political scientists does not subscribe to this straightforward relationship between Muslim communities and Muslim MPs/MLAs. They tend to analyse the question of political representation in a much more nuanced manner. See, as a representation of these views, Faruqi (2020), and Allie (2024). An underlying belief that the Muslims of India constitute a homogeneous community with collective and fixed interests leads to measuring the community’s underrepresentation in politics through the proportion of Muslim legislators to the community’s numbers. This simple, uncomplicated, and ahistorical formulation is hardly a definitive method to measure Muslim representation in purely quantifiable terms.

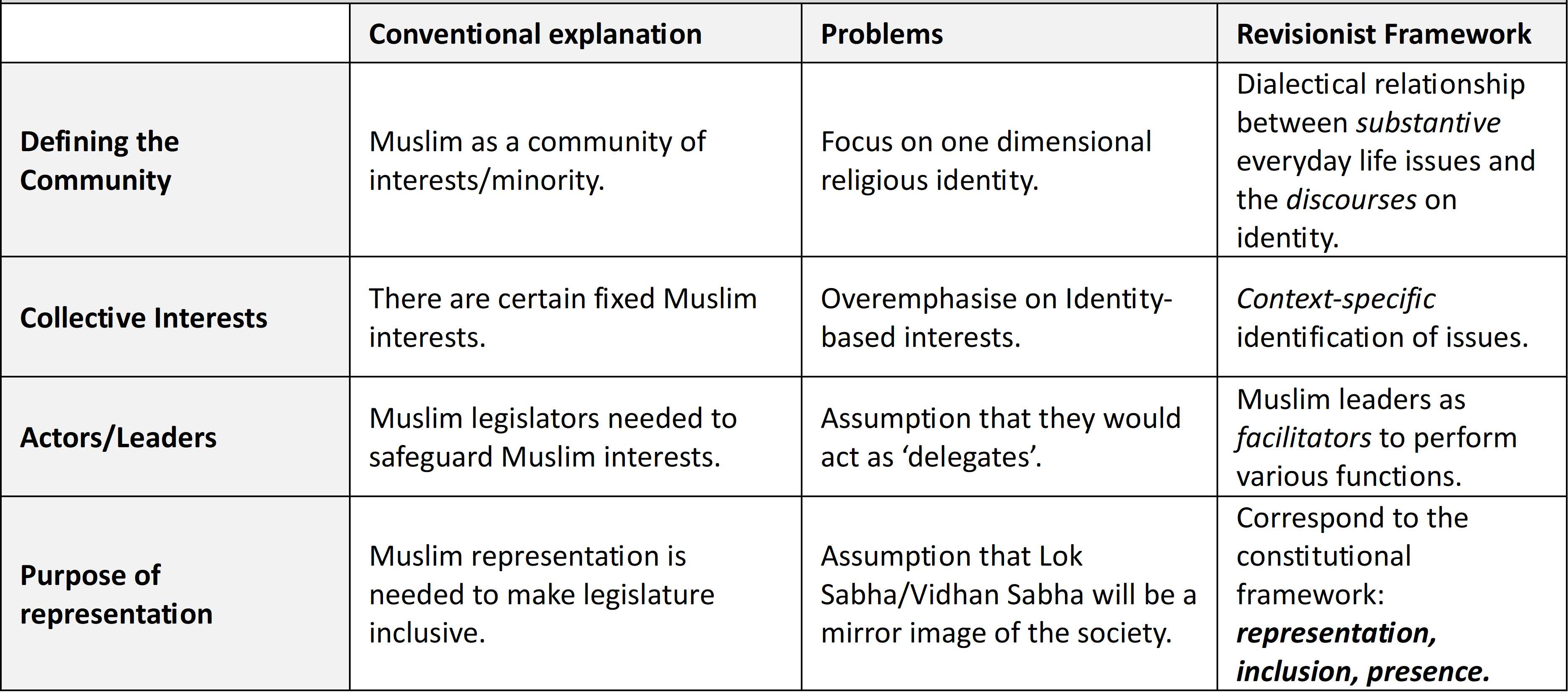

There are four key facets of this claim: the constitution of Muslims as a political community; an imagination of a set of collective Muslim interests; the expected role of Muslim leaders (or legislators in the formal sense) in safeguarding these interests; and, finally, the possible outcome of this process for the democratic character of the polity. Examining each of these will unravel the provocative implication behind the claim: that Muslims need to be represented only by Muslims.

Identity formation

How is Muslim identity discursively produced? I make an analytical distinction between substantive Muslimness and the discourse of Muslimness (Ahmed 2024). Substantive Muslimness underlines the real-life meanings of being a Muslim in local context, while the discourse of Muslimness transforms Muslims into a national question.

Respondents may define themselves primarily as Muslims, yet do not hesitate to reveal their caste and/or sectoral affiliation.

Factors such as caste, language, economic status, sect, region become the determining factors that constitute substantive Muslim identity and collective self-perceptions in a particular socio-political context (Ahmed 2019). On the other hand, the discourse of Muslimness relates to the ways in which collective Muslim presence in India is perceived, explained, debated, rejected, and even ignored. Treating Muslims as a ‘faith community’ in purely religious terms, evoking their religious distinctiveness as a ‘minority’ in legal-constitutional discourse, measuring their demography in census-driven terms, depiction of mediaeval ‘Islamic rule’ as Muslim history and the media debates on global jihad and radicalisation produce a powerful discourse of identity. Muslim individuals are eventually linked to these pan-Islamic imaginations in order to produce grand explanations. These ready-to-use templates of Muslim identity also influence Muslim self-perceptions at the grassroots level.

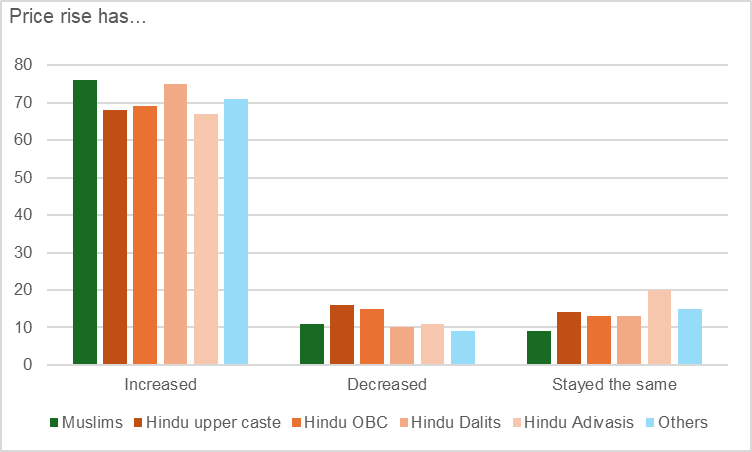

Muslim communities do not find any apparent contradiction between substantive Muslimness and the discourse of Muslimness. In surveys, respondents may define themselves primarily as Muslims, yet do not hesitate to reveal their caste and/or sectoral affiliation. Some even identify as ‘Muslim scheduled caste’ or ‘Muslim Dalit’ – a category which does not have any legal-administrative validity. 2A Presidential Order of 1950 introduced religion as a defining criterion for inclusion in the scheduled caste (SC) category. As a result, only Hindu caste groups were eligible for SC reservation. Dalit Sikhs and Dalit Buddhists were included in the SC list later. This makes the category exclusionary as Muslim Dalits and Christians Dalits are not eligible to avail the benefits of reservation as scheduled castes.

The distinction between the discourse of Muslimness and substantive Muslimness and should not be overestimated, as if the former is false consciousness and the latter alone is real. Muslim identity formation swings, pendulum-like, between the extreme positions of the conception of a single Muslim community in India and more immediate cultural-local considerations. In other words, between the discourse of Muslimness and substantive Muslimness.

Collective interests

The ‘collective interests’ of Muslims in India can be understood meaningfully if they are seen in relation to this complex, multilayered, and discursive constitution of Indian Muslim identity.

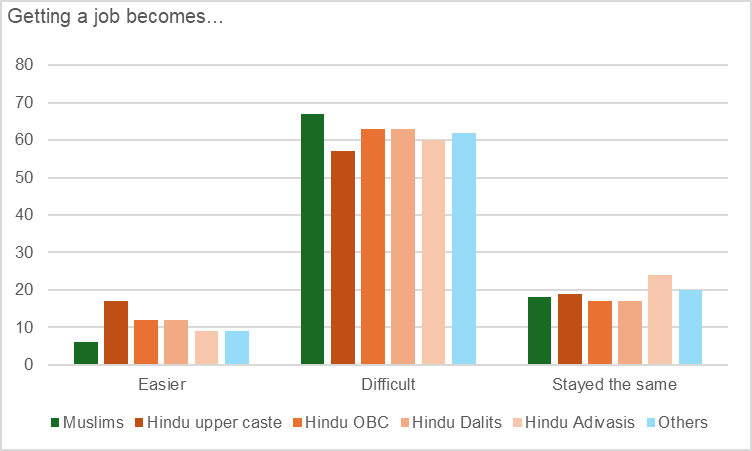

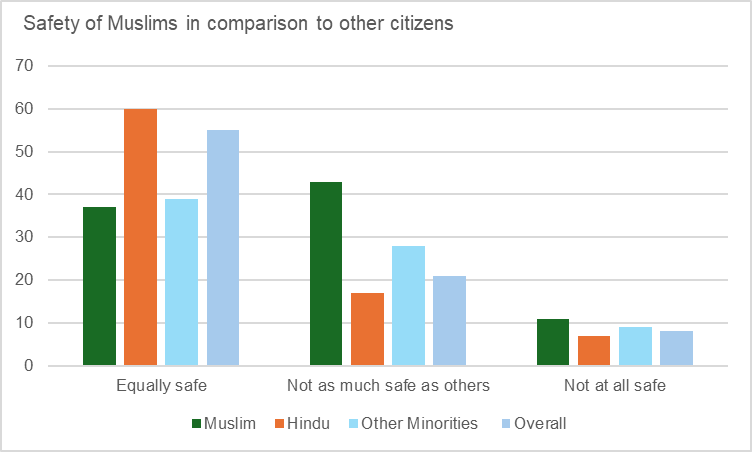

Substantive Muslimness remains a major source of inspiration for Muslim communities to reclaim their citizenship status in secular terms. In a recent study (Ahmed, Alam, and Parveen 2025), we found that Muslim communities tend to describe growing unemployment, lack of development, price rise, and increasing economic disparity as their major concerns.

The CSDS-Lokniti prepoll survey from 2024 substantiates this observation.

Figure 1: Substantive Muslimness and collective Muslim interest

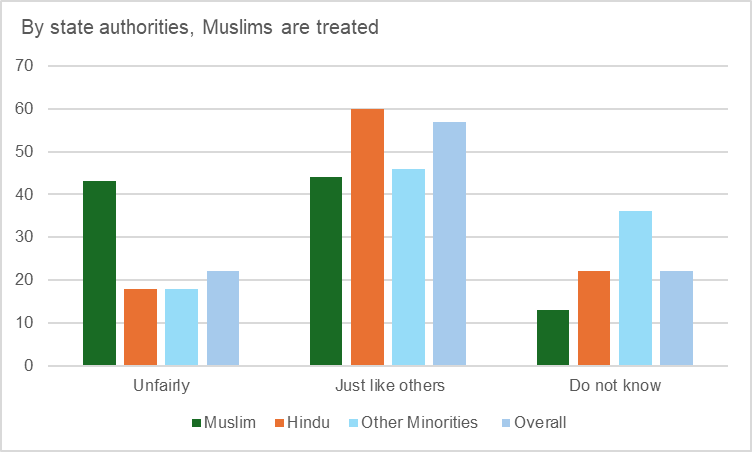

This does not, however, mean that the Hindutva-dominated environment does not affect collective Muslim imaginations. There is a growing apprehension that Muslim religious identity and its collective existence as a constitutionally recognised minority community is seen as a problem category in the present environment. More than half of the Muslim respondents in a 2024 survey claimed that they were unsafe. They were split almost equally on whether Muslims were treated unfairly by the state authorities.

Figure 2a: Discourse of Muslimness and collective Muslim interest

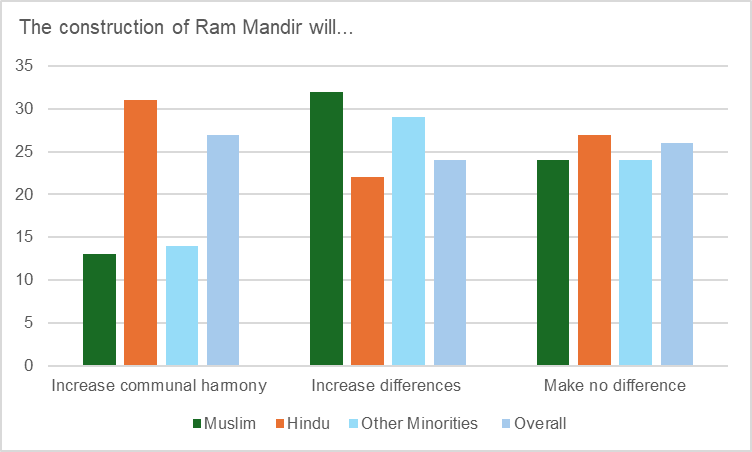

These findings may lead us to two possible conclusions. First, unfair treatment of Muslims by state authorities has been so normalised that many Muslims do not think that it could even be reported. Secondly, it is also possible that Muslims have accepted the Hindutva-driven administrative norms of governance as a new reality that has to be engaged without conflicts or contestations. It is revealing that nearly 40% of Muslims avoided responding to in the affirmative to a question on whether the construction of Ram temple would hurt communal harmony.

Figure 2b: Discourse of Muslimness and collective Muslim interest

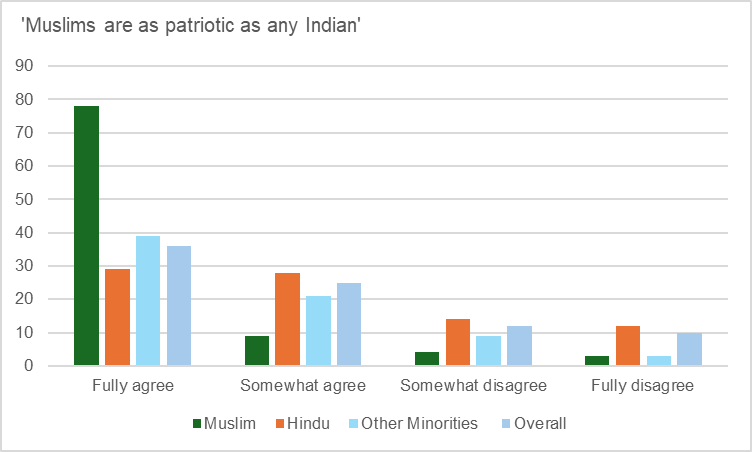

Faced with the apathetic attitude of the state as well declining social relations with Hindus, Muslim respondents assert their nationalism in a profound manner. Over three-fourths identify themselves as highly patriotic. These findings are related to each-other. Muslim self-perceptions are certainly determined by socio-economic considerations that make up substantive Muslimness. At the same time, the dominance of Hindutva as a determining discourse of Muslimness is taken seriously as an existential question by Muslim communities.

Representation

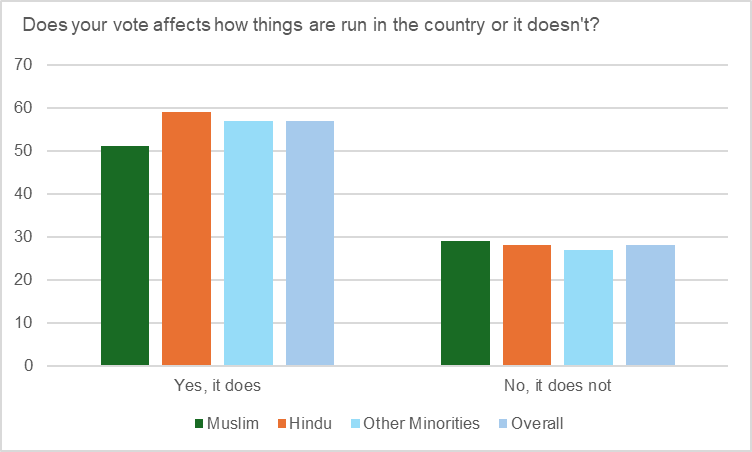

The high Muslim turnout in 2024 (62%) confirms that a significant majority envisages democratic processes as a possible way out to protect their identity both as individual citizens as well as a threatened minority. More than half of Muslims believe that their vote does make a difference. Despite being ignored by the entire political class, Muslim communities have not lost faith in politics.

Figure 3: Efficacy of votes

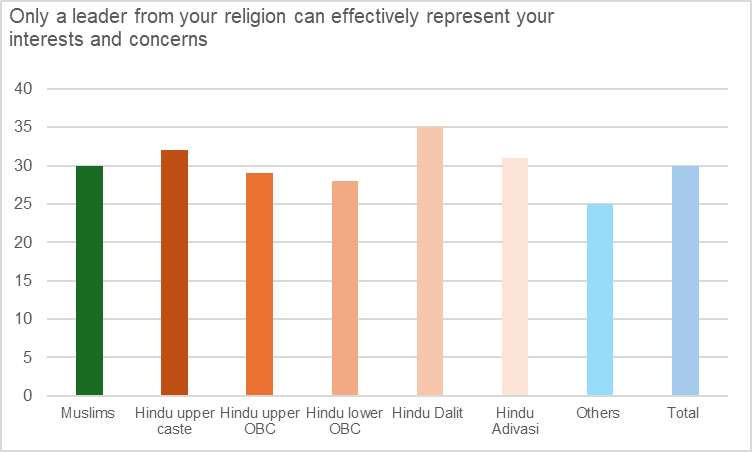

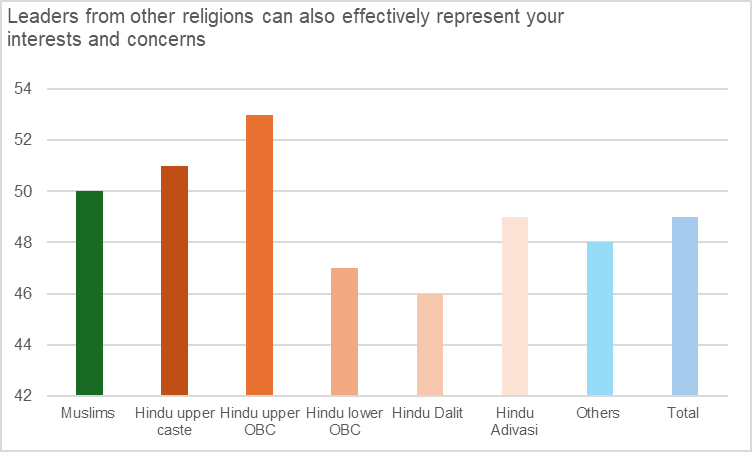

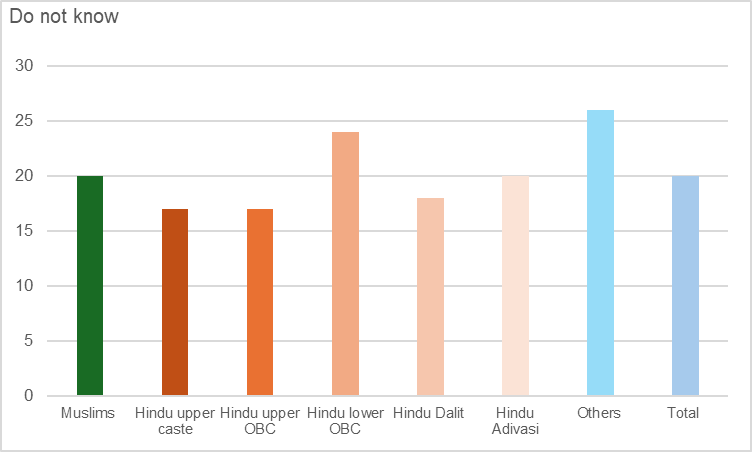

The data show that almost half of Muslim voters assert that the religious background of a leader is not a major consideration for them to vote. However, nearly one-thirds of Muslims claim that their interests and concerns can be represented effectively only by a leader from their own community.

Figure 4: Who represent Muslim interests?

This diversity of Muslim opinions clearly underlines the specific nature of Muslim voting patterns over the years. Muslims, like any other socio-religious group, come together for asserting themselves as a collective political entity (Thakur 2016).

Yet, religious affiliation is not the only criterion which encourages Muslims to become a consolidated group of voters. Caste configurations too play a decisive role, especially in areas where Muslims are in a decisive majority. Religious identity is a context-specific phenomenon, and Muslim voters adhere to a highly practical approach for establishing a correlation between the religion of a candidate and their multifaceted collective interests.

The BJP accommodates only the ‘right kind’ of Muslims [...] On the other hand, non-BJP parties are not very excited to mobilise Muslim politicians since they are confident that they have a monopoly over Muslim vote.

The Bihar assembly elections of 2020 are a good example. Muslim caste-groups became a ‘community of voters’ in the Muslim-dominated Seemanchal region. However, this was not the case with rest of the seats where Muslims were not electorally powerful. The CSDS-Lokniti Bihar 2020 (post-poll) survey also confirm this trend.

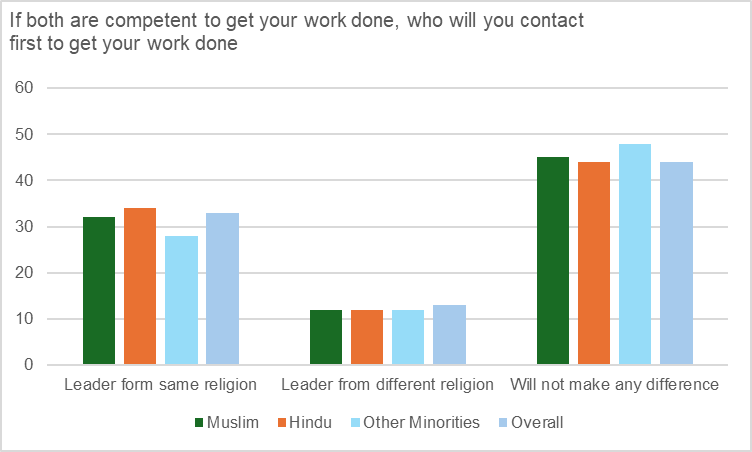

This ‘practical approach’ needs some elaboration. A significant majority of Muslim respondents claims that they do not hesitate to approach leaders from any religion for getting their work done. Only 31% say that they would prefer to contact a Muslim leader in the first instance.

‘Getting work done’ is not related directly to electing an individual leader. Instead, it is about the accessibility of a political representative. This accessibility, in most of the cases, becomes crucial at the local level. Hence, ‘getting work done’ is about addressing those substantive issues that affect Muslims at the grassroots level.

Figure 5: How to get work done?

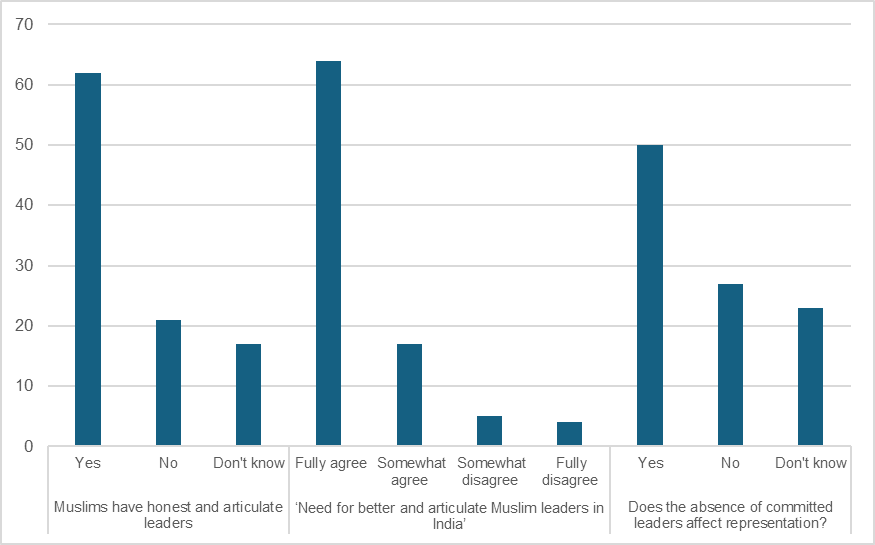

Muslim communities, nevertheless, do not always follow an interest-oriented utilitarian approach about Muslim leadership. An overwhelming majority of Muslim respondents claim that Muslims do have honest and committed leaders. On the other hand, an equal number think that there is a need to have more articulate Muslim leaders in India.

These two sets of claims appear paradoxical, but they underline a complex Muslim response. The honesty of an individual leader is a subjective issue. A Hindutva dominated environment has affected the status and bargain power of Muslim politicians.

Figure 6: Muslims and their leaders

The BJP accommodates only the ‘right kind’ of Muslims, who are expected to toe the party-line and contribute – even if indirectly – to the media-driven anti-Muslim discourse (Ahmed 2024). On the other hand, non-BJP parties are not very excited to mobilise Muslim politicians since they are confident that they have a monopoly over the Muslim vote. Against this backdrop, it is natural for Muslim leaders to strengthen their organic linkages with the Muslim community they intend to represent.

The response indicates Muslim communities adhere to a realistic picture of politics. They are sympathetic to the idea of Muslim representatives. Yet, they are fully aware of the fact that Muslim leaders, especially the professional politicians, do not necessarily function as community representatives; instead, they often follow the ‘party-line’ to make themselves relevant in the competitive sense (Ahmed 2019)

Conclusions

Let us now return to the question posed at the onset: do Muslims need to be represented only by Muslims? Muslim self-perception as a community, the identification of a few overlapping concerns as collective Muslim interests, and a highly complex assessment of Muslim leadership validate my initial claim that the question of representation cannot be answered in a simple and straightforward manner. These Muslim responses can only be understood if we interpret them in relation to the multi-level institutional framework that sets the norms of election-driven representative politics in India.

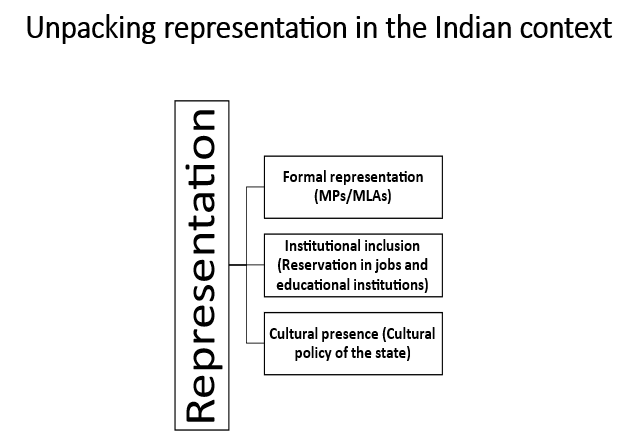

Constitutional provisions underline three distinct forms in which representation as an idea is expressed: formal secular representation in legislative bodies, institutional inclusion through affirmative action, and cultural presence through rights for religious minority groups. These three forms of representation are inextricably linked to each other. Formal secular representation is effective, if the inclusive character of state-institutions is recognised and the state follows a cultural policy that accommodates minority cultures. Any possible disturbance in this equilibrium might lead to secular majoritarianism. 3For an excellent discussion on the idea of secular majoritarianism, see Menon 2024.

Muslim communities are conscious of this equilibrium of representative democracy. They tend to define themselves as secular voters to assert their substantive Muslimness, which explains their faith that leaders from other religions can effectively represent their interests.

The Muslim views on their socioeconomic backwardness and marginalisation underlines a very different expectation. In this case, representation is observed as a form of institutional inclusion. The demand to include Pasmanda Muslims in the SC list is a clear manifestation of this trajectory. The search for a secured environment in India and an overwhelming self-claim for patriotism show that Muslims realise that their public presence has been demonised by a powerful media-driven anti-Muslim propaganda. In this case, the representation is sought in the form of collective presence to reclaim a space in the Indian cultural and political life. Muslim leaders, in this schema, are not envisaged as representatives; instead, they are expected to function as facilitators to engage with the political system at various levels.

Muslim representation must be understood in relation to inclusions of Muslims in the institutional apparatus and the positive portrayal of their religious cultural identity in the public domain.

Let me conclude by proposing a revisionist framework to explore Muslim political representation in contemporary India.

Muslim representation: A new framework

This framework is based on three considerations. First, there is a need to democratise the idea of representation itself. The conventional debate on Muslim representation relies entirely on the flawed assumption that Muslims can only be defined as a religious community (or as a minority) for the purpose of representation. Muslim sociological diversity must be accepted, along with the concerns of Muslim Dalits, Muslim women, and poor Muslims.

Second, we must expand the contours of the present debate. For that purpose, the democratisation of the wider institutional apparatus becomes very significant. We should not only look at the Lok Sabha and state assemblies as the possible avenues to evaluate Muslim representation. Instead, the nature of Muslim representation in the Rajya Sabha, Vidhan Parishads of the states, urban civic bodies and even Panchayats must be explored. 4I have tried to do a systematic study of Muslim representation in the Rajya Sabha to understand how political parties, including BJP, adhere to a few unwritten norms to bring in favorable Muslim leaders of their choice in Parliament via the Rajya Sabha. (Ahmed 2016).

At the same time, we must also pay close attention to the internal making of political parties to assess their inclusive character. Do they have any set mechanism to include marginalised groups, in this case Muslims? How do they decide candidates to contest polls? Do they have regular internal party elections? These questions are very crucial because political parties have become highly centralised and there is no discussion on their democratic and secular credentials.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we must closely look at the constitutional schema of representation to understand the nature of legal-administrative structures and the expected functions of elected representatives. Muslim representation, in this case, must be understood in relation to inclusions of Muslims in the institutional apparatus and the positive portrayal of their religious cultural identity in the public domain.

Hilal Ahmed is an associate professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), New Delhi. He works on political Islam, Indian democracy, and politics of symbols.

(This article is an outcome of the Muslims in India (MI) project funded by the Henry Luce Foundation. I am grateful to Sudipta Kaviraj, Suhas Palshikar, Ashutosh Varshney, Christophe Jaffrelot and Tariq Thachil for their comments and suggestions on the initial draft of this paper. A shorter version of the main argument of this research was published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India, Univrsity of Pennsylvania, in its newsletter, India in Transition.)