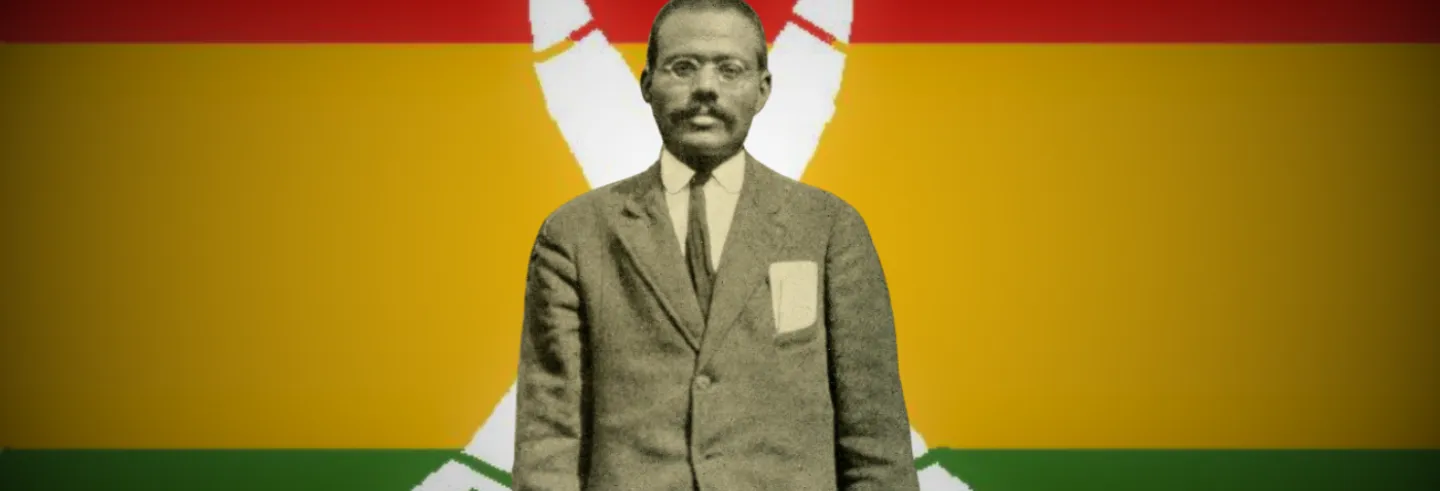

In 1954, in his book Scenes and Portraits, writer and critic Van Wyck Brooks reminisced about a friend, Har Dayal. In 1912, they had been colleagues at Stanford University.

Har Dayal, he wrote, lived “like a saint or a fakir in a small room near the railroad, with only a single chair for an occasional guest. He slept on the bare floor, for he had no bed, disdaining even a rug to cushion him, as I found when he spent a night sometimes at my house, living on milk and unbuttered bread, with one old brown tweed suit, detached as he was from the vanities of the world, and the flesh” (Wyck Brooks 1954).

To Wyck Brooks, Har Dayal perfectly exemplified Mikhail Bakunin’s definition of the ideal revolutionist. Bakunin, a leading figure of anarchism, wrote in his Revolutionist’s Catechism that the revolutionist has “no interests, no affairs, no feelings, no attachments of his own, no property, not even a name”, for he has “broken with the codes and conventions that govern other people, nor is he bound to these, and has only one thought, one passion: revolution”.

In September 1912, Har Dayal resigned from Stanford after only seven months to devote himself, among other things, to the Radical Club—its full name being the International-Radical-Anarchist-Communist club—in the Palo Alto area. A few months later, he would emerge as a founding member of the Ghadar party, formed by Indians then on the west coast to free India by revolutionary means.

Formative Years

In his years in California, during America’s “Progressive Era” (1870–1920), Har Dayal found himself in the midst of several radical movements. Anarchism was in the air; industrial workers were drawn towards trade unionism; dubious and now discredited theories like “eugenics” promoting the superiority of some races over others were widely discussed; and it was the dawn of the “new woman”, with calls, among other things, for women’s independence in every sphere, for their right to vote and to seek higher education in fields long denied them.

Har Dayal was a prolific writer, engaging deeply in philosophies and ideologies popular in his lifetime. The fluidity apparent in his writings poses a challenge to biographers and historians alike, yet his days in the US had a profound influence on Har Dayal, especially on the concept of “self-culture”, which, he believed, was vital to an anarchist’s creed (see Zachariah 2013; Elam 2013, 2014).

Between 1912 and 1934, the year his Hints for Self-Culture was published, Har Dayal moved between advocacy of revolution to pacificism. Arguing, at one time, for independence from imperialism, he later advocated a utopian “world state” founded on friendship between all.

An assessment similar to Wyck Brooks was made by Bhai Parmanand, another Har Dayal associate. The two had met during their years in England.

In 1906, Har Dayal, then aged 22, had secured a generous government scholarship to Oxford University. Drawn by the powerful political currents of the time, especially the India House-based organisations led by Shyamji Krishnavarma, V.D. Savarkar, and others working secretly for India’s independence, Har Dayal underwent a political transformation of his own and gave up studying for a degree at Oxford.

According to Har Dayal’s biographer, Emily Brown (1975), in these early days as a revolutionary, Har Dayal did take the oath of the Abhinav Bharat, Savarkar’s secret society, and also wrote about cow protection in some of his early pieces, but even then a generous eclecticism prevailed in his beliefs.

Har Dayal ‘used to sleep on the hard ground, eat some boiled grain or potatoes and be engaged the whole day, except for a short time devoted to study, in meditation’.

He was, for instance, friends with Guy Aldred, an “anarcho-socialist”, a free press defender, and (with his partner Rose Witcop) an early proponent of family planning. Aldred’s publication of censored versions of Krishnavarma’s Indian Sociologist, especially the issues relating to Madan Lal Dhingra’s 1909 trial (Dhingra was executed for the murder of British official Curzon Wylie), had earned him a year’s imprisonment.

As Parmanand wrote in his own autobiography in 1934, Har Dayal wished to set up a new religion like the Buddha’s and subjected himself to similar austerities. Parmanand saw this for himself two years later in 1910 when the two were together in Martinique, then a part of the Dutch West Indies in the Caribbean. He wrote that Har Dayal “used to sleep on the hard ground, eat some boiled grain or potatoes and be engaged the whole day, except for a short time devoted to study, in meditation”.

Radicalism at Stanford

A decade before Har Dayal reached the US in 1911, the presence of “Hindus” on the west coast had drawn attention and censure. The “Hindu invasion”, though their numbers were small (about 5,200 along the US west coast and Canada in 1910) was seen as a threat to jobs and livelihoods by groups such as the Asiatic Exclusion League that also targeted other Asian immigrant labour (see Bagri 2017).

Xenophobia led to riots in several cities in 1907, and passage of racist acts like Canada’s Continuous Journey Act (where emigrants had to journey without “stoppage” so as to enter legally, something impossible for those from India).

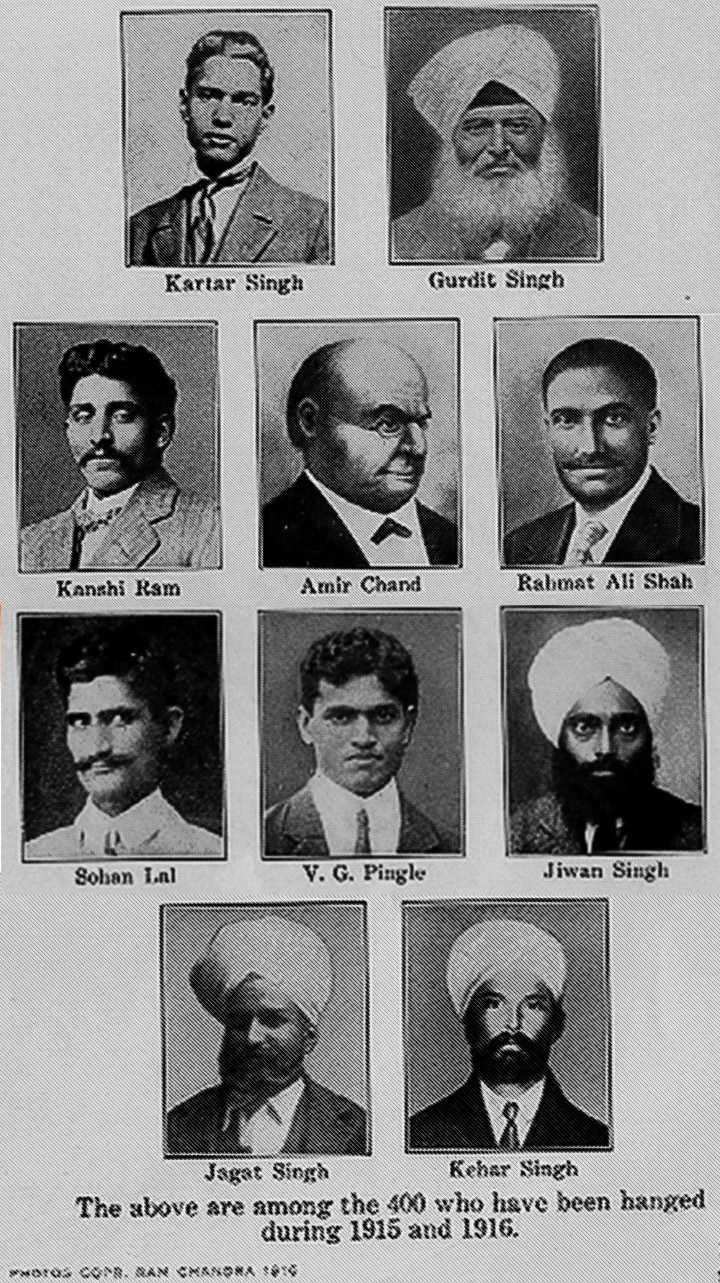

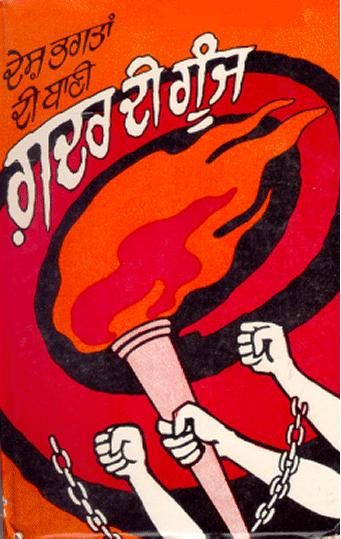

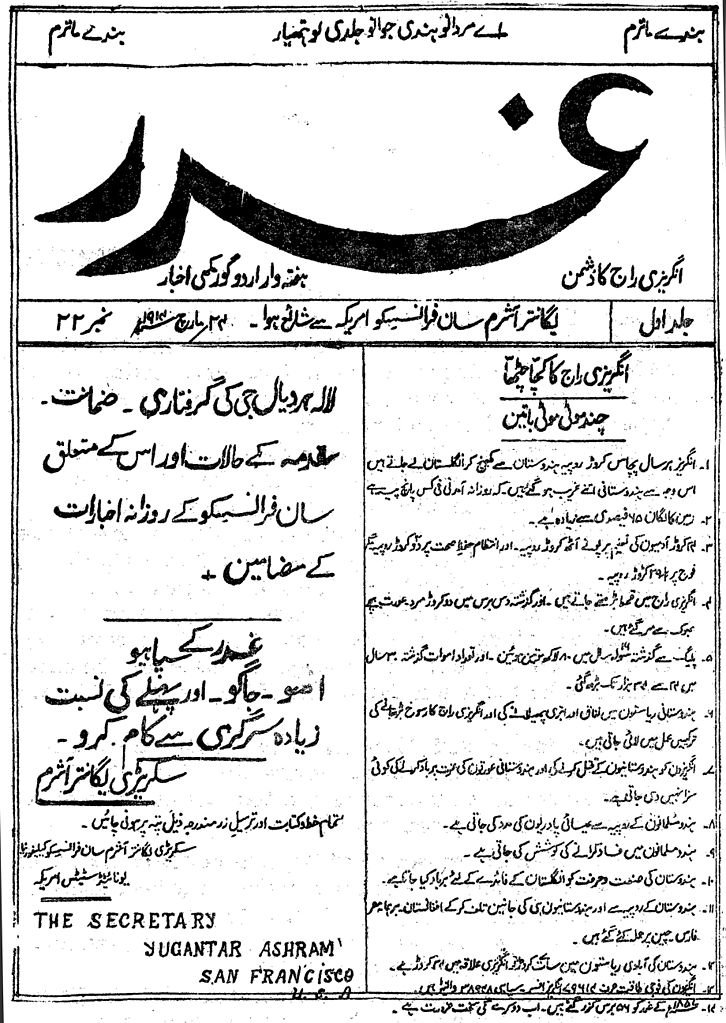

In May 1913, Har Dayal joined several Indians then in US—prominent among them, Kanshi Ram, Sohan Singh Bakhna, Taraknath Das, Guran Ditt Kumar—to formally set up the Ghadar (revolution) party, first in Astoria in Oregon, and then San Francisco. The Ghadar believed that the humiliation of Indians in the US stemmed from India being under British rule and Indians being colonised subjects.

Har Dayal soon emerged as the Ghadar’s main ideologue. Freedom secured by revolutionary means, the Ghadar believed, would ensure an end to racism and imperialist domination.

Har Dayal … befriended novelist Jack London, in whose last novel, The Little Lady of the Big House (1916), he makes an appearance, first in chapter 10, as ‘Dar Hyal’.

In San Francisco in March 1911, Har Dayal’s lectures on Indian philosophy at the Theosophy Hall got him attention and won him influential friends. Among them were Fremont Older, editor of the San Francisco Bulletin, then involved in several progressive causes, such as ending corruption and capital punishment.

Har Dayal also befriended writers such as John D. Barry, known to have Irish republican sympathies; and others like progressive politician Hiram Johnson, and novelist Jack London, in whose last novel, The Little Lady of the Big House (1916), Har Dayal makes an appearance, first in chapter 10, as “Dar Hyal”.

“He’s a revolutionist, of sorts. He’s dabbled in our universities, studied in France, Italy, Switzerland, is a political refugee from India, and he’s hitched his wagon to two stars: one, a new synthetic system of philosophy; the other, rebellion against the tyranny of British rule in India. He advocates individual terrorism and direct mass action. That’s why his paper, Kadar, or Badar, or something like that, was suppressed here in California, and why he narrowly escaped being deported; and that’s why he’s up here just now, devoting himself to formulating his philosophy” (London 1916).

Har Dayal’s interest in anarchism only grew in his time at Stanford. Malcolm Harris’s recent book on the history of Palo Alto, where the university first developed in 1885, mentions Har Dayal as one of the anarchic, free-spirited individuals who gave the city its distinct culture (2023). Har Dayal drew the “community’s revolutionaries” into his “Radical Club” and threw himself into the movement.

As Parmanand wrote, “Har Dayal never occupied a middle position; he was always going from one extreme to another. Almost immediately from communism he had passed to anarchism. Both at the University and outside he soon started an open campaign against the institutions of marriage, property, and government.”

David Starr Jordan, then president of Stanford University was, as several accounts go, impressed by Har Dayal’s credentials. He had little idea then that Har Dayal had not finished his degree at Oxford, or of his association with the India House group, and the anarcho-socialists. Jordan, an ichthyologist by training, had consolidated his position as Stanford’s President after a long face-off with Jane Stanford, the University’s co-founder, along with her husband, Leland. Even today, Jordan is suspected of involvement in Stanford’s poisoning. Jordan’s support of eugenics has led recent movements in the Palo Alto region to rename schools named after him.

The rise of the phrase ‘new woman’ coincided with the suffragette movement and the increased drive of women for education and employment.

Har Dayal’s resignation from Stanford in September 1912, Harris writes, came soon after an alarmed Jordan received notes of a recent Radical Club meeting about “heroes, who have killed rulers … and dynamited buildings”. In December that year, the Radical Club held demonstrations in San Francisco against the death penalty.

Equally controversial that same month was Har Dayal’s support of the so-called “free love” contract marriage between Carleton Washburne and Heluiz Chandler. The contract, with the couple agreeing before their marriage on certain stipulations, was radical for its time and earned the couple, in their early twenties, and those supporting them—Har Dayal was one of a vocal minority—considerable ire and ridicule.

Free Love Contract

For many newspapers, the contract, especially Heluiz’s wish to be independent in every way, evoked H.G. Wells’ 1909 novel on the “new woman” called Ann Veronica. Wells’ protagonist left her home chafing at restrictions imposed on her. She supported herself financially, and boldly declared her love for a man with a “sullied reputation”. Wells’ novel, despite its happy ending, was deemed scandalous for its time.

The term “new woman” was popular in the late 19th century and several writers used it frequently. Henry James wrote about Isabel Archer in his Portrait of a Lady as a “new woman” who lived life according to her terms and by her own means. The rise of the phrase coincided with the suffragette movement and the increased drive of women for education and employment.

Har Dayal, vocal in his support for the Washburnes, found himself singled out for criticism. Carleton Washburne was one of his best friends, and Har Dayal admired his courage and wisdom in defying “custom and conventionality by entering into this so-called ‘free love’ contract”. He declared, “As a consistent and convinced opponent of the entire fabric of slavery and hypocrisy that is called the ‘marriage system’ I am proud to claim Washburne as a pioneer of women’s freedom in this country,”

A columnist at the Sacramento Bee scoffed at this notion of freedom. The sanctity of marriage was the foundation of a nation. Anyone who taught otherwise was a traitor, and a foreigner who did so could not be tolerated “in our schools, either under state or other control” the columnist wrote on 21 September 1912.

In the Peninsula Times Tribune of 18 September 1912, Har Dayal explained his views on marriage at length. “The present system of marriage is a relic, condemning women to economic dependence. A woman is denied of her individuality … It prevents the free moral and moral development of women. … It makes impossible real friendship between men and women. It creates social segregation and enforces a monastic life. It makes impossible the scientific breeding of the human race by giving precedence to the claim of economic overlordship, over those of hygiene and eugenics.”

Carleton Washburne was one of his best friends, and Har Dayal admired his courage and wisdom in defying “custom and conventionality by entering into this so-called ‘free love’ contract”.

Such thoughts also preoccupied London and he gave free rein to his opinions in The Little Lady of the Big House. The character of Paula was based on his wife, Charmaine Kitteridge, who epitomised the “new woman” of the times, and the two men fascinated by her, Dick Forrest, Paula’s husband, and Evan Graham, an old associate, were versions of Jack himself.

The “new woman” had featured in other London novels as well. The heroine of his first novel, Daughter of the Snows, was the Stanford-educated Frona Welse who shocked everyone by befriending Native American women and prostitutes. In addition to being an intellectual, Frona was also athletic, as was Paula of London’s last novel.

London was criticised for his portrayal of “unrealistic women characters”, but as critic Clarice Stasz wrote, such women did exist in California, scattered within “its nascent middle class and university settings. In the 1890s they rode bicycles, hiked mountains, and spoke on platforms alongside men. They were a definite minority, albeit a visible one” (2017).

The Little Lady of the Big House is an expositional work, dilatory in style. Almost every current issue of the day is a debatable topic for its characters—the “independent” woman, the concept of eugenics, and even advanced farming concepts. Dar Hyal, the Indian revolutionary, provides a stodgier, at times comic, counter to Dick Forrest’s radical thought experiments. One passage is especially revealing of Forrest’s (and perhaps London’s) egregious views on eugenics, when, in response to Dar Hyal’s leading questions, he draws a comparison between “Hottentots” or the “average Melanesian” and “white men”.

The Anarchist’s Creed

A month after leaving Stanford University, Har Dayal’s framing of “The Anarchist’s Creed” made news in several Californian newspapers. He was the leading figure of “Fraternity of the Red Flag”, an anarchist group, and also involved in a six-acre campus in Oakland, informally labelled the Bakunin Institute of California or the “first monastery of anarchism”. The creed was dedicated on “Ferrer Day” (October 12), in memory of Spanish anarchist and educator Francisco Ferrer.

As per the creed, members had to commit to the principles of radicalism and take several vows. For instance, a member had to renounce wealth and promise not to earn money. Every social tie and obligation had to be repudiated so to live a life of simplicity and hardship. Another vow included a life of service and propaganda. There were also “eight principles” emphasising personal development—intellectually, through self-culture; morally, through love and self-discipline; and, physically, through hygiene and eugenics. Institutional revolution would be achieved through communism and the ending of private property.

Har Dayal’s vision of a world free of imperialism ended in disillusionment by the time World War I ended, and his view that anarchists would aid the revolution in India ended up as wishful thinking.

Other principles included the search for fraternal cooperation, abolition of coercive government, promotion of sciences, the end of religion, and the complete independence of women with the abolishing of marriage, prostitution, and any institution that perpetuated their enslavement. The creed also envisioned the setting up of a “Modern School”, where children aged between 12 and 16 would be taught the principles of this fraternity.

The very next year, Har Dayal became involved in the Ghadar party. He wrote regularly for its newsletters and was its chief propagandist, where he advocated a violent end to British rule.

Har Dayal’s vision of a world free of imperialism ended in disillusionment by the time World War I ended, and his view that anarchists and other rebels would aid the revolution in India ended up as wishful thinking. His commitment to anarchism led to his surreptitious exit from the US in March 1914. He lived the rest of his life in various parts of Europe before returning to England in 1927 and the US in 1938. Carleton and Heluiz Washburne remained happily married the rest of their lives and both did well in their respective careers.

On Har Dayal’s death in March 1939, his friend Barry described him as a “well-behaved propagandist”. To Har Dayal, as he suggested in Hints for Self-Culture (1934), anarchism was a way of being, a system of living, and a path to finding individual fulfilment through self-culture, which would lead to a “world-state” based on friendship between individuals.

Anuradha Kumar writes for ‘Scroll’, ‘Economic and Political Weekly’, and other publications. Her most recent novel is 'The Hottest Summer in Years' (Yoda Press, 2021).