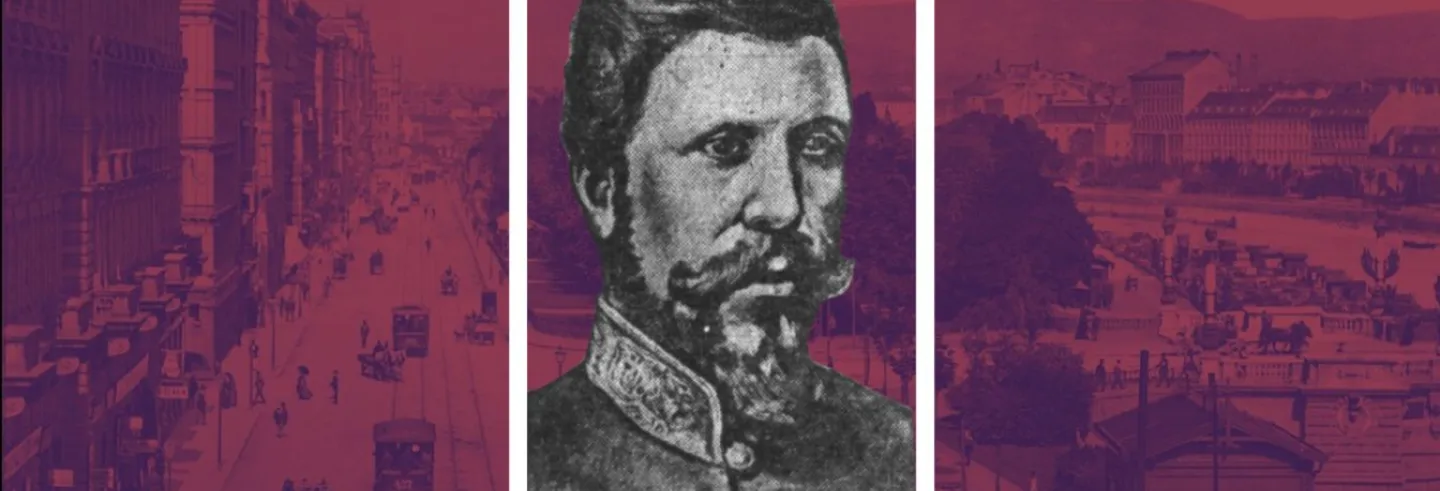

In 1890, Johann Salvator, an estranged nephew of the Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph, disappeared off the coast of South America. He had, some years ago, left the Viennese court after coming to blows with the emperor following court intrigue. Beginning life again as a commoner, Johann Salvator took on the name ‘John Orth’

Soon after Orth went missing, many individuals surfaced, claiming to be the lost man.

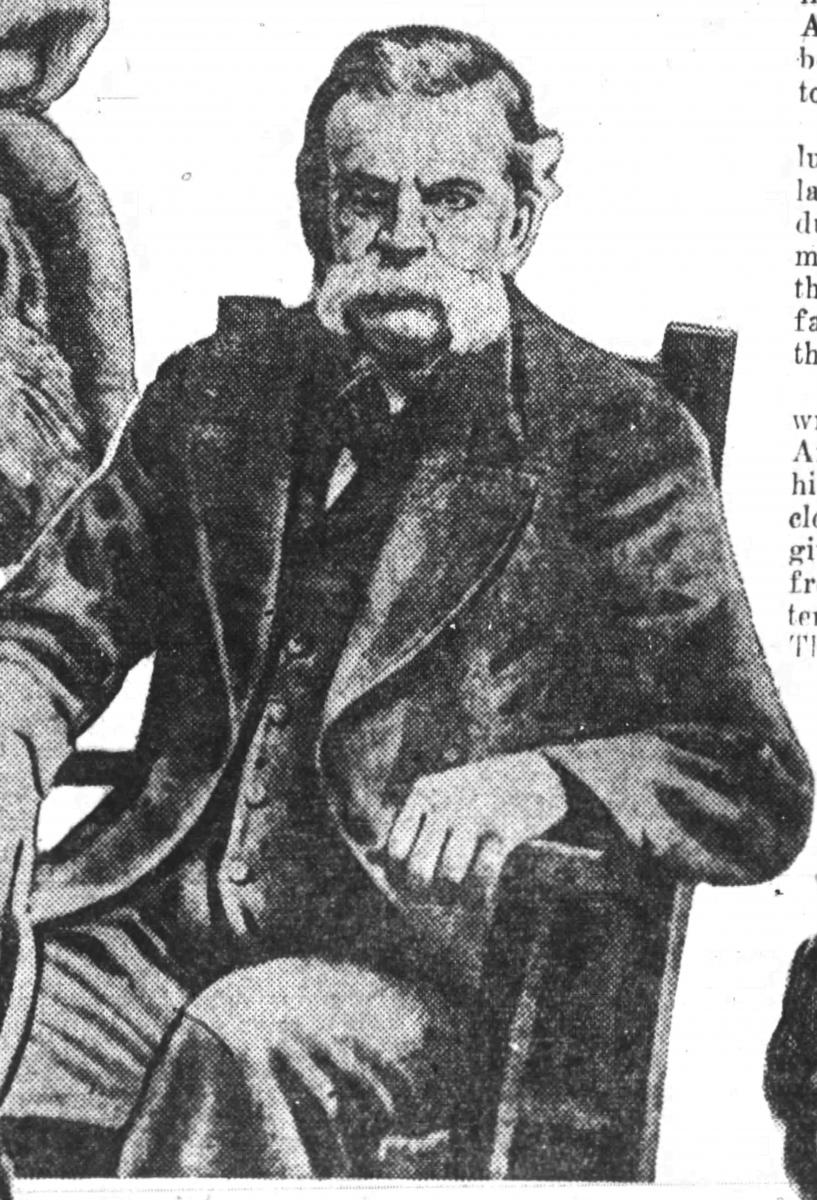

None appeared more credible than a guru of eastern esotericism, Orloff N. Orlow, who died in a New York hospital in 1924.

Deathbed revelations

As newspapers of the time reveal, Orloff N. Orlow’s death in April 1924 set off immense speculation. A “healer”, and dabbler in spiritualism, Orlow, who had moved from California a decade earlier, had gathered around him a devoted group of disciples — mainly women — lecturing to them about eastern religions and myths and helping them find “inner peace”. His esoteric philosophy at times resembled the teachings of the Theosophists. It included, as Orlow said, an amalgam of beliefs culled from his understanding of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Zoroastrianism.

Orlow claimed he had negotiated on the czar’s behalf with Lenin in Switzerland in the early 1900s and even staved off the Russian revolution for several years.

In the days following Orlow’s death, revelations came in thick and fast.

The attending doctor affirmed that Orlow, in his delirium, had related events in the Viennese court, which only an insider could claim familiarity with. Another of Orlow’s followers, Charlotte Fairchild, a society photographer, said he had spoken in Sanskrit.

A former tenant couple of Orlow, the Tamayos, were quoted in the Dayton Daily News (13 April 1924) as claiming that Orlow had been engaged in translating the Vedas from Sanskrit to English. According to them, Orlow had claimed that his mother was from the family of the former Duke of Tuscany in Italy, as indeed the Archduke had been. From his father’s side, he had been related to Czar Alexander II. As the Tamayos detailed, Orlow claimed he had negotiated on the czar’s behalf with Lenin in Switzerland in the early 1900s and even staved off the Russian revolution for several years!

Despite the lack of definitive evidence, Salvator’s name was engraved on Orlow’s coffin.

Two women claimed to have incontrovertible proof that Orlow and Salvator were indeed the same. Charlotte Fairchild stressed she was in contact with someone in London who had a definitive photograph of John Orth — the name Salvator took after he gave up his royal titles. A comparison would establish the similarities between the two men. Laura Doehler, a New York bookseller, who had in her records several signatures of Orlow, also promised confirmation of identity from the same mysterious contact. The latter apparently had signed letters from John Orth sent to the former owner of the Sainte Marguerite, the ship responsible for Orth’s mysterious vanishing act in 1890. A match of the signatures would confirm Orlow’s identity. But the mysterious visitor from London deposited the documents in a safe and left to “explore the country”. He never reappeared.

Despite the lack of definitive evidence, Salvator’s name was engraved on Orlow’s coffin. One of the attendees at the funeral, a former official at the Austrian embassy corroborated the belief that Orlow and the missing archduke were the same.

Things took a murky turn when Grace Wakefield, a young woman who was Orlow’s supposed ward —though some insisted she was his wife —, died by suicide only some days later. She was found dead alongside her two parrots and pet spaniel, all poisoned, the New York Times reported. To complicate things, she seemed about the same age as Salvator’s wife, who had disappeared along with him on the ill-fated ship in 1890.

That was the year the mystery of Johann Salvator began.

Travails of an archduke

Johann Salvator, born in 1852, was the son of Leopold, the former grand duke of Tuscany who had abdicated once the campaign for the unification of Italy gathered pace in the 1860s. The family moved to Vienna, where their cousin was the Hapsburg emperor.

The crown prince and Salvator were also opposed to the Viennese court’s overweening interest in the occult and the new-fangled system of theosophy.

In Vienna, the adult Salvator incurred the displeasure of the emperor. Salvator supported the Crown Prince Rudolf in his frowned-upon love for the young Mary Freiin von Vetsera. The crown prince and Salvator were also opposed to the Viennese court’s overweening interest in the occult and the new-fangled system of theosophy. As Karl Baier writes, in 1884, Salvator and Rudolph devised a plan to successfully convict of fraud one of the most famous professional mediums of the time, the American Harry Bastian who had had Vienna enthralled for many months. That same year, Rudolf published his critical Einblicke in den Spiritismus (Insights into Spiritualism), in which he branded the “spiritualist movement as a public danger and called for an alliance of the Catholic Church and science to combat it.”

Before his death in 1924, Orlow had sent a letter to the Vatican purporting to reveal the truth behind Rudolf’s death.

Five years later, Rudolf was later found dead with von Vetsera, his lover, in a hunting cabin. While the deaths were ruled as caused by ‘suicide,’ speculation never quite died away. Salvator suspected foul play, for the court had disapproved of the prince’s alliance, and had a showdown with the emperor. The two men came to blows, a misdemeanour that led to exile.

(Incidentally, before his death in 1924, Orlow had sent a letter to the Vatican purporting to reveal the truth behind Rudolf’s death. The Vatican laughed the matter off, its spokesperson labelling it the kind of prank usual in carnival season.)

Salvator gave up his royal prerogatives after he married a ballet dancer of the Viennese opera, Ludmilla or Milli Stubel. Taking on the name of John or Johann Orth, he moved to London. It was here, the story goes, that he had had the idea of turning to business. Leasing the ship Sainte Marguerite, in July 1890 he set sail toward South America. Its cargo was cement, the new in-demand product in a rapidly urbanising world. A month later, soon after the ship left Buenos Aires for Valparaiso in Chile, it vanished after a storm. No trace was found of John Orth, Milli Stubel, or the 24 crew members on board.

Within a few months, however, numerous John Orth sightings were reported: the stories ranging from the bizarre to the surreal to the very improbable. (Some of them were compiled by The Oakland Tribune on 14 February 1926). One account claimed that he had fought in Chile’s civil war of 1890-1891, between President Jose Balmaceda and Congress over power-sharing, and survived it to purchase a ranch in Uruguay. A few years later, Orth emerged in the US. In this telling, he had been the owner of a plantation on the island of Martinique, a French colony. His wife and children had perished after Mount Pelée, an active volcano in the region, erupted.

Over the years, a peddler in Vienna, machinist in Ohio, a Norwegian lithographer, a New York promoter, all variously claimed to be the lost archduke.

In 1895, as the Sino-Japanese war broke out in the east, the Japanese general Yamagata was rumoured to be Orth himself, the speculation fuelled by the apparent resemblance between the general’s tactics with those mentioned by Salvator in his manual, according to the Kansas City Star (23 April 1905). A Swedish fisherman claimed to have seen Orth at the helm of the Sainte Marguerite in Arctic waters. Over the years, a peddler in Vienna, machinist in Ohio, a Norwegian lithographer, a New York promoter, all variously claimed to be the lost archduke.

But it was Orlow’s account that fascinated many. After his death, the St Louis Post-Dispatch reported (13 April 1924) that a former ship captain, Colonel David Collier, surfaced to offer the details to fill in the missing gaps in his story,

According to Collier, Salvator alias Orth alias Orlow had survived the storm at sea and set up home in Porto Alegre in Brazil. After his wife’s death, he sailed to India and China, where he extensively studied philosophy. He returned after many years to Chicago, where he opened a school to teach his thought system. He lived successively in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle, before at last, finding his feet in New York.

A world pre-surveillance

Salvator’s movements, his unexplained disappearance, and his later emergence in various avatars were possible in a world before modern surveillance came to prevail, and where travel did not require extensive documentation.

Before the regime of documentation, the ‘freedom’ from surveillance permitted a seamless shift of identities and a chance to make oneself anew.

Till the 19th century, documents to monitor travel and guarantee identity were rarely used. The scholars Nik Brandal, Eirik Brazier and Ola Teige quote the British historian A.J.P. Taylor, who wrote that before the First World War, a “sensible law-abiding Englishman could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state” and a foreigner could spend a lifetime in Britain without “a permit and without informing the police.” Things changed with the rapid rise of rail travel in Europe and America and the increased movement of people across the Atlantic and the Pacific from the 1890s onward. By the early 20th century, the need to monitor migration and the demands of a rapidly militarising world propelled the need for surveillance and intelligence. The idea of a worldwide passport standard emerged only in 1920, in the aftermath of World War I, championed first by the League of Nations.

The British were arguably pioneers in modern-day state-sponsored espionage and intelligence-gathering. The rise of revolutionary activity in India and the need to monitor the rising numbers of emigrants from the Punjab to the US and Canada, most of whom would soon be part of the Ghadar movement, prompted the setting up of a British monitored global intelligence network.

But before the regime of documentation, the ‘freedom’ from surveillance permitted a seamless shift of identities and a chance to make oneself anew. Salvator’s unaccounted disappearance ensured stories proliferated about him. It also gave the frequently disgraced Orloff Orlow a chance to do a vanishing act and to take on other identities, more than once.

Philanthropist, rug-dealer, spy, spiritualist

Of all the claimants to being Orth, Orlow was the most intriguing, his story of makeovers as complicated as Salvator’s disappearance.

Orlow taught his esoteric mix of different eastern religions, extolling the concept of the ‘Atmos’ – a derivation of ‘Atman’ the universal soul.

Orlow, as newspaper records show, surfaced first in Chicago, as a lecturer on Hindu philosophy and occult subjects via his Brotherhood of Divine Humanity, set up in 1899. Orlow taught his esoteric mix of different eastern religions, extolling the concept of the ‘Atmos’ – a derivation of ‘Atman’ the universal soul that was also one of seven principles of theosophy, devised by Helene Blavatsky. Orlow too, like Blavatsky, at times claimed to be Russian. In Chicago, he also pursued laudable aims of taking care of the sick and even engaged a doctor to ensure this. This fizzled out after the doctor claimed that he had lent money to Orlow and never been paid for his services.

This would be a pattern throughout Orlow’s career, for he did not quite get along with associates. A.E. Walklett, a spirit medium who doubled up as Orlow’s business manager. was not paid for months. According to Walklett, he had been lured away from a thriving practice in Chicago, and Orlow had not repaid a debt of $2000. A furious Walklett threatened to ‘bathe him (Orlow) in vitriol’ and take the matter to court, according to the San Francisco Examiner, (22 November 1902).

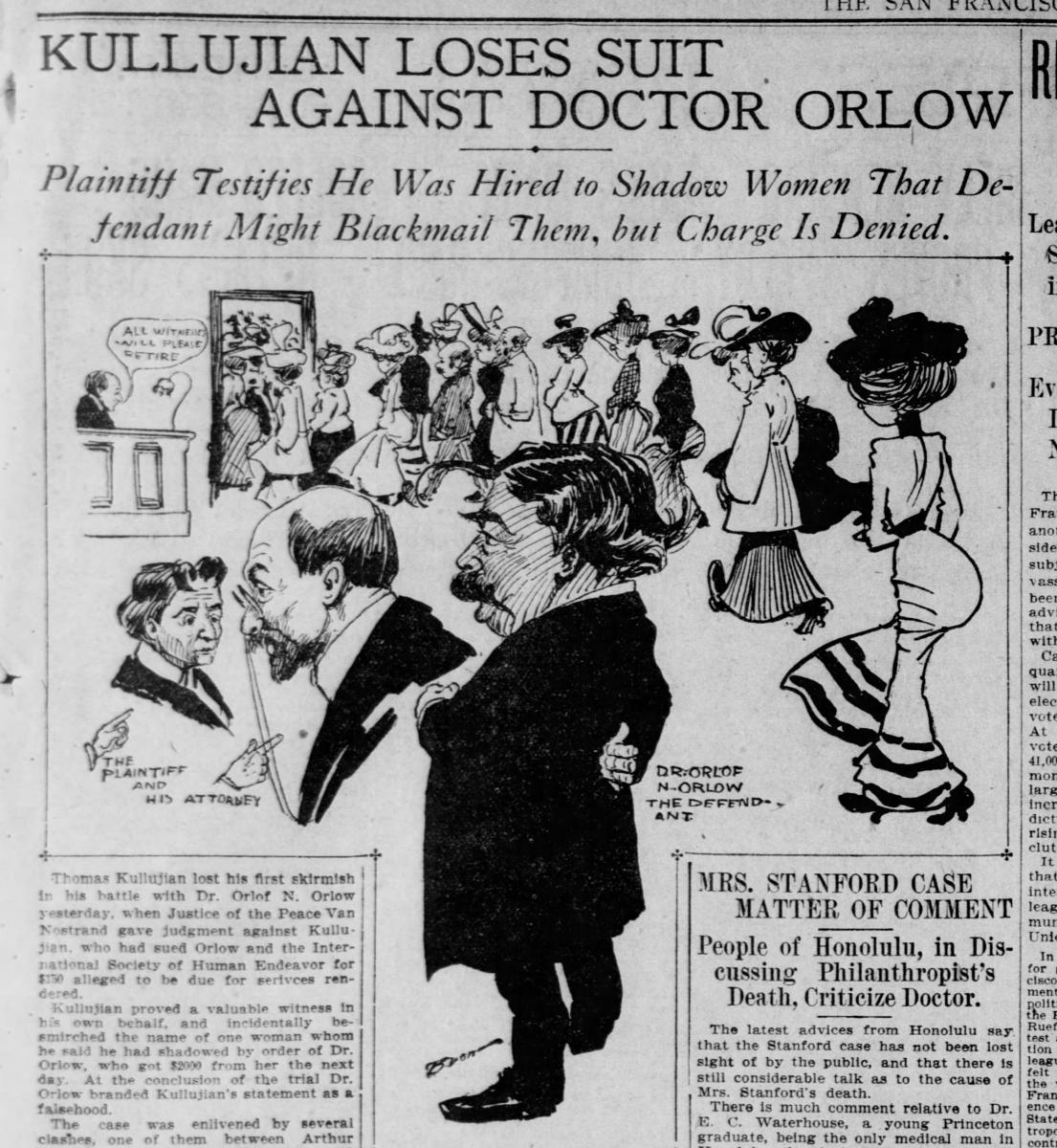

Thomas J. Kullujian, an Armenian emigrant, accused Orlow of extorting money from rich widows and of spying on California naval bases for the Russian.

Orlow moved to San Francisco, where he set himself up in impressive premises and a new business: a rug and carpet dealership that displayed rare and expensive material from around the world. Orlow also gave lectures as part of the newly named Orlow Institute or the Society of Human Endeavour and brought out a newsletter to describe the powers of ‘Atmos’. An Oakland newspaper of the time explained Orlow’s "Atmos or Ath-mos" philosophy as the "belief in successive incarnations, or periods of life experiences” necessary for “humankind to truly comprehend the nature of life, and purpose of existence”. (Some issues of Orlow’s journal, Atmos, can be found here.)

He continued to have legal wrangles with employees. Thomas J. Kullujian, an Armenian emigrant, accused Orlow of extorting money from rich widows and of spying on California naval bases for the Russians, a claim reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, (26 July 1905). Orlow did indeed serve prison time for two months after he was convicted of embezzling $2500 from his former employee. The stand-off exhausted most of Orlow’s resources and cost him his reputation as well. Orloff soon moved to Seattle and in 1915, surfaced in New York, selling Japanese prints. All through his chequered career, he was often accused of passing off fakes.

The Hapsburgs refused to countenance the fact that anyone stepping forward as Salvator could be authentic.

His post-mortem claims to be one of the Hapsburgs never cut much ice. In any case, Johann Salvator had been declared officially dead by the Austro-Hungarian government in 1911. The Hapsburgs refused to countenance the fact that anyone stepping forward as Salvator could be authentic. Not one of them had the aquiline Hapsburg nose. Moreover, as other intrepid reporters noted, Hapsburg men were almost always invariably bald. The claimants, strangely, always had a head full of hair.