The Disaster Management (Amendment) Act, passed in December 2024 has been celebrated by the home ministry as one of “the game-changing provisions of the law” to build a disaster-resilient country. ‘Game-changing’ evokes a sense of transformative impact, much like the “paradigm shifting” label stuck to the Disaster Management Act at its inception in 2005. Such terms set high benchmarks, making it crucial to critically evaluate whether they can truly deliver on their promises of transformation.

India’s disaster management legislation was a response to the growing awareness at the turn of the century of the lack of a structured legal and institutional framework.

Disaster relief had carried over colonial-era templates of action. Until 2002, the agriculture ministry was the nodal ministry, a result of “calamity” being almost solely imagined as droughts or floods that wiped out crops, making provincial revenue-cum-agriculture officers the state’s frontline relief agents (Hall-Matthews, 1998).

It was also an ad-hoc process. When disaster struck, a crisis management group at the centre chaired by the Central Relief Commissioner gathered situation reports and asked states what assistance they needed. Those reports were forwarded to a National Crisis Management Committee, where the cabinet secretary and ministry secretaries tried to align departmental actions. This inter-ministerial group then reviewed assessments made by central teams and attached cost estimates. At the end of this process, a High-Level Committee, comprising union ministers, would sit to approve financial assistance to affected state.

Institutions are not just a tool through which the reform are to be introduced, but rather the very site of the reform.

Once this committee signed off , the temporary chain dissolved. The same ladder had to be rebuilt from scratch the next time a disaster struck.

Through the 1990s, successive disasters laid bare a systemic weakness in this disaster-governance architecture: the absence of a permanent, tiered apparatus that could anticipate risk, enforce standards and mobilise resources without waiting for Delhi’s ad-hoc committees. The 1991 Uttarkashi earthquake levelled non-engineered masonry that had never been retrofitted and cut the sole access road into the valley, proving that building codes and alternate routes existed largely on paper (Arya, 1992). Two years later, the Latur earthquake found Maharashtra with no statutory emergency plan; response depended on spontaneous self-organisation and quickly stalled when local networks were overwhelmed (Comfort, 1995). In 1999, the Odisha Super Cyclone exposed the final link in the chain: early-warning messages and relief supplies failed to reach last-mile communities because of poor communication and coordination networks across various levels of governance (Ray-Bennett, 2016).

These disasters triggered extensive discussions on India’s capacity to manage emergencies effectively. A High-Powered Committee on Disaster Management in 1999, chaired by J.C. Pant, emphasised the need for a shift from a reactive to a proactive approach, focusing on preparedness, mitigation, and institutional coordination. A draft disaster-management bill idled in Parliament, before it was fast tracked by the Gujarat earthquake of 2001 and the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

Behind the legislation lay a desire for a new institutional centred on preparedness and mitigation, but also one that would bypass the political conflicts and claims inherent in humanitarian crises (Bose, 1994; Kumar, 2016).

The act fit within the then ruling United Progressive Alliance government’s “legislation-based mindset, addressing issues through formal legal frameworks,” a retired high level bureaucrat told me, adding that it “gave a technocratic solution for a deeply political process”.

Always on

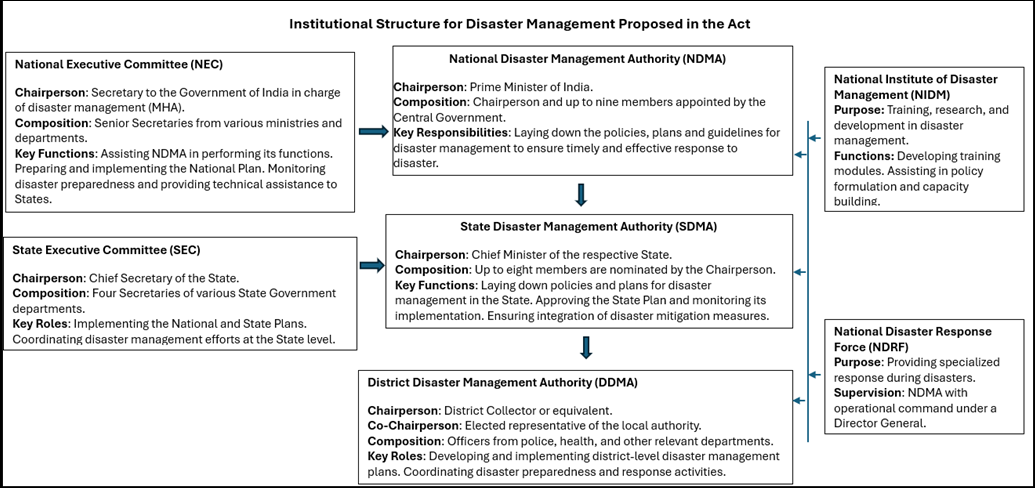

In place of the old, single-use ladder, the 2005 act proposed an ‘always-on’ and interlinked grid. District, state and national nodes would exchange information continuously; training and developing response capacity would be permanent, not improvised; and money should travel along predefined channels, reducing the dependence on one-off ministerial decisions.

Figure 1: Outline of the institutional structure as proposed in the Disaster Management Act 2005

The technocratic reshuffle greatly simplified—indeed depoliticised—the complex power dynamics of disaster management. The streamlined institutional set-up struggled to deliver the paradigm shift it had promised. The NDMA was formally at par with the home ministry, but the symbolic elevation never translated into operational authority. Control over budgets, personnel, logistics, and the nationwide chain of command remained inside the home ministry, whose relief division had historically handled calamities. The result was an overlapping and ill-defined division of labour: the NDMA issued guidelines and vision statements, while day-to-day decisions, resource allocations, and emergency deployments continued to flow through home ministry desks.

This bifurcation bred chronic role confusion, duplicated structures, and turf battles, stalling the act’s intended shift from reactive post-disaster relief to anticipatory mitigation and preparedness.

Evidence of these structural flaws surfaced quickly.

A Special Task Force of the home ministry that reviewed the act’s performance in 2013 painted a stark picture: most statutory bodies below the national level were “non-functional,” existing largely on paper; NDMA guidelines had rarely been implemented; and the authority lacked the legal teeth or financial muscle to enforce compliance. The Task Force concluded that without clear lines of command, dedicated budgets, and professional staffing, the NDMA could not fulfil its mandate (Government of India, 2013).

India is unquestionably better equipped to save lives quickly, but only marginally better at preventing losses.

Post the review, the NDMA was restructured. Its nine-member team was reduced to four, and their ranks downgraded. The NDMA effectively became one of the organisations under the home ministry, assigned the roles of policy-making and planning. Disaster preparedness, response and relief were handed over to the ministry While the changes provided greater clarity in roles, it also set a clear prioritisation for disaster management: emphasising response and relief under the home ministry over mitigation and long-term planning under the NDMA.

The ‘game-changing’ 2024 amendment to the Disaster Management Act formalises the division of power as exists in practice. There is now statutory recognition for National Crisis Management Committee and the High-Level Committee. The NDMA has been positioned as a technocratic advisory body for disaster management policy and planning. The National Executive Committee (NEC) and its state counterparts no longer will write plans and micromanaging implementation, only coordinate and monitor.

What is new is the provisioning for Urban Disaster Management Authorities in every state capital and in cities with over a million people. There is also a shift away from recognising compensation as a government obligation in disaster response, emphasising relief efforts instead. The amendment reframes government payouts as discretionary relief, not a justiciable right. Loan-repayment moratoria and concessional credit survive, but only for calamities the centre designates “severe,” creating a two-tier universe of eligible and non-eligible victims.

Reflections

The Disaster Management Act’s two-decade-long journey culminating in the latest amendment shows that new laws do not wipe the slate clean; they settle into the grooves carved by older arrangements. India’s disaster relief machinery, housed in the home ministry and steered by committee has remained intact throughout. It goes on to show that while institutions are often seen merely as implementing arms of policy decisions, in reality, they are products of past policy priorities. This means they carry legacy structures, power dynamics, and institutional inertia that shape their functioning. Introducing policy changes without recognising institutions as entities in their own right overlooks a key factor in the reform process. Institutions are not just a tool through which the reform are to be introduced, but rather the very site of the reform.

Previously, top-down amendments in institutional structures without any consideration of existing power hierarchies have resulted in little more than cosmetic alterations, such as renaming existing departments while preserving the same hierarchy (Ogra et al 2021). This has led to the appropriation of the terminology of the new paradigm, which undermines the intended reforms. This phenomenon is described by Stables and Scott (Stables and Scott, 2002) as policy ‘sloganisation’.

In case of disaster management, early outcomes highlight this complexity. The NDRF, focused on improving response efficiency in line with the original nature of the disaster management approach, has delivered visible successes, from Cyclone Phailin (2013) to the Joshimath tunnel rescue (2023). At the same time, state and district disaster management Plans that were to introduce the mitigation-based approach, helping transition from Disaster Management to Disaster Risk Reduction, have struggled to find real meaning and use on the ground.

What does this mean for future security and resilience? Since the introduction of the Disaster Management Act, India is unquestionably better equipped to save lives quickly, but only marginally better at preventing losses. Legacy chains deliver fast relief; legacy mind-sets resist long-term risk regulation. Closing that gap demands more than another organisational layer: it requires binding fiscal allocations for mitigation, statutory data-sharing across utilities, and political incentives that reward states for reducing exposure, not just for distributing relief.

Enhancing resilience against prolonged and compounded risks will hinge on how effectively the conceptual shift in disaster understanding and management transforms existing institutions.

Recognising institutional legacies, then, is not an academic aside—it is the starting point for realistic disaster policy. Reforms will work when they repurpose entrenched capacities (logistics, command discipline) while eroding entrenched blind spots (weak regulation, reactive finance). Until that dual task is embraced, India’s disaster governance will remain stronger at response than at resilience, and the transformative promise of the Disaster Management Act will stay only partially fulfilled.

Encouraging signals do exist. Since the 2005, every state has a State Disaster Management Plan. Mock-drill frequency—one proxy for preparedness—has doubled in a decade. Fatality rates from cyclones have fallen sharply: Phailin (2013) and Yaas (2021) together killed fewer than 100 people, compared with more than 9,000 in the 1999 Odisha Super-Cyclone. Real-time warning lead times have expanded from hours to days, allowing DDMAs to stage phased evacuations rather than last-minute scrambles. Meanwhile, the Finance Commission’s dedicated mitigation window shows that prevention is at last receiving a predictable revenue stream.

Yet early stress fractures are also visible. Urban flood losses keep climbing, signalling that newly mandated Urban Disaster Management Authorities would have to translate land-use prescriptions into practice in order to be effective. Climate-linked extremes—glacial-lake bursts, heatwaves—still fall between multiple ministries, exposing gaps in hazard-specific expertise.

In summary, India demonstrates measurable improvements in responding to sudden disasters. However, enhancing resilience against prolonged and compounded risks will hinge on how effectively the conceptual shift in disaster understanding and management transforms existing institutions.

Anshu Ogra is an assistant professor at the School of Public Policy, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi.