By Swathi S. Balachandra, Vaibhav Agavane, Navya M.S., Padmavathi, Prashanth N. Srinivas

India is one of the few countries that has systematically organised its health system around the principles of primary healthcare. National and state governments have set up primary health centres and sub-health centres across the country, helping protect many Indians from health-related and financial shocks.

However, the primary healthcare system is only as strong as its workforce. The Covid-19 pandemic response depended on the tireless efforts of frontline workers, who continued working despite the risk of losing their loved ones. With the upgrading of sub-health centres into Ayushman Arogya Kendras from 2018, a new cadre of frontline workers—Community Health Officers (CHOs)—was introduced into primary healthcare teams.

These centres, earlier called Ayushman Bharat–Health and Wellness Centres and then Ayushman Arogya Mandirs, were renamed Ayushman Arogya Kendras in Karnataka. The intent was to move away from selective services and provide comprehensive primary healthcare closer to people’s homes, with trained CHOs leading the Arogya Kendra teams and delivering an expanded range of services.

In Karnataka, CHOs are professionals with at least a Bachelor of Science in Nursing, and many also hold master’s degrees. The state has made appreciable progress in upgrading its sub-health centres to Arogya Kendras. As of 28 February 2023, a total of 9,285 Ayushman Bharat–Health and Wellness Centres had been made operational in Karnataka.

Yet, eight years after the launch of this programme, several systemic issues still need attention if CHOs are to provide comprehensive primary healthcare in Karnataka. In this article, we present the systemic factors that shape how CHOs function and recommend measures to enable them to play this role effectively.

We draw on three main sources. First, we use our field interactions and reflections from districts in Karnataka. Second, we review government documents and reports related to the programme. Third, we incorporate insights from conversations with leaders of the Karnataka CHO union on their views about the role and the implementation of the programme.

Too Many Vacancies

Positive changes have been reported in people’s perception and trust, clinical care and follow-up, patient footfall, service delivery, home-based care, and overall team support since the upgrading of facilities to Ayushman Arogya Kendras and the posting of CHOs. The fact that the presence of even a single additional provider can significantly enhance service delivery, utilisation, and community confidence shows how severely primary-level facilities have been historically understaffed. This understaffing includes shortages of Medical Officers, staff nurses, Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) orPrimary Health Care Officers (PHCOs) as they are called in Karnataka, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), Health Inspection Officers (HIOs), and group-D staff.

Vacancies in other cadres, such as PHCOs, ASHAs, staff nurses, and medical officers, are also high and reduce the capacity of CHOs to function effectively as team members.

Comprehensive primary healthcare can be effectively delivered only through a team-based approach. Each cadre within the Arogya Kendra team—CHOs, PHCOs, Health Inspection Officers, and ASHAs—has complementary capacities and responsibilities and cannot substitute for one another. A vacancy in even one of these posts affects the workload of all staff and the overall quality of care.

In Karnataka, a total of 7,045 CHO posts have been sanctioned, with 5,849 (83%) in position and 1,196 (about 17%) vacant, including 683 vacant posts and 513 centres that are yet to be upgraded. Recruitment processes for CHOs have not taken place since 2022, and the Government of Karnataka has repeatedly returned the recruitment budget to the central government in the financial years 2024–25 and 2025–26.

Existing CHOs are often deputed or made “in charge” of Arogya Kendras where vacancies exist. As a result, vacancies not only affect the villages served by Arogya Kendras without a CHO but also lead to sub-optimal attention in more than 1,000 additional Arogya Kendras, because their CHOs are burdened with extra responsibilities. These vacancies are often concentrated in areas where services are needed the most; for example, vacancies were observed in remote areas with tribal settlements.

Vacancies in other cadres, such as PHCOs, ASHAs, staff nurses, and medical officers, are also high and reduce the capacity of CHOs to function effectively as team members. Out of 9923 sanctioned posts for PHCOs in Arogya Kendras across Karnataka, around 42.4% were vacant in 2024–25.

According to Indian Public Health Standards, in addition to a CHO, there must be either one Auxiliary Nurse Midwife and one male Multipurpose Worker or two Auxiliary Nurse Midwives at each facility. In Karnataka, however, there is only one Auxiliary Nurse Midwife per Arogya Kendra, and even this post has vacancies. Overall, the sanctioned strength of human resources in Karnataka is lower than Indian Public Health Standards norms.

A 2024 report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India documented a 27% vacancy of medical officers and a 67% vacancy of staff nurses in primary health centres, along with 51% vacancies in “other posts” and vacancies among ASHAs in all districts, ranging from 7% to 87%. CHOs reported that they are often asked to perform the duties of medical officers or staff nurses because of these vacancies, which prevented them from being consistently available to their own communities. Village members also felt that the CHO was available only two or three days a week, which created a sense of unreliability and led to loss of trust.

“As we go for duty at the Primary Health Centre there, people here feel we are not around … this thought gets imprinted in their mind,” observed a CHO in a rural Arogya Kendra.

A Secure Workforce

CHO posts, like many other posts in healthcare, continue to be contractual. This arrangement strains team dynamics, reduces workforce motivation and sense of ownership, and ultimately harms the quality of care for communities.

Because the CHO position is contractual and underpaid, and because it is a newer cadre with different professional qualifications than the regular post of PHCO, staff described a competitive team dynamic. This competition undermines teamwork and weakens the ability of the CHO to play an effective leadership role. Although guidelines promised that CHOs would be absorbed into regular posts after six years of service, no steps have been taken to make this happen.

For staff to feel a stronger sense of ownership, the state must take responsibility for primary healthcare and invest adequately in human resources.

Delays in salary payments, failure to honour promised increments, and overall low pay without benefits are all features of this contractual arrangement. CHOs expressed strong motivation and commitment to serve their communities, yet some were considering leaving their posts because of job insecurity, inadequate pay, and the burden of repetitive reporting and target-driven work. According to records shared by the Karnataka CHO union, more than 1,000 CHOs have resigned so far.

Another recent step that signals disinvestment is a Karnataka government order to “rationalise” ASHAs by increasing the population covered by each worker. This was opposed through statewide protests by the Karnataka State United ASHA Workers’ Association in August 2025. Since ASHAs are often the first point of contact between the health system and the community, this move can seriously undermine maternal, child, and overall health, especially in remote rural, tribal, and urban slum areas.

For staff to feel a stronger sense of ownership, the state must take responsibility for primary healthcare and invest adequately in human resources. Strengthening primary care is possible only with a strong, committed, and secure workforce. All vacancies need to be filled, and posts must be regularised with fair compensation. At the heart of primary healthcare lies the human connection between a caring workforce and the community, rather than sophisticated equipment as in tertiary care settings.

Real Role of CHOs

The idea that India’s primary healthcare system needs mid-level providers has been discussed in policy circles for decades. There is ample evidence that primary care led by nurses or other mid-level health providers can be effective, and this has finally taken shape in the role of the CHO. However, the vision for what CHOs can achieve in the primary healthcare system remains narrow.

Many doctors are reluctant to shift clinical tasks and believe that CHOs should not provide clinical care. As a result, CHOs often end up as an extra pair of hands under the Medical Officer at the Primary Health Centre. Instead, CHOs should be recognised as independent providers embedded in the community who can address a wide range of primary care needs, with Medical Officers serving as sources of continuous mentorship.

A closer look at the way workload and recommendations are conceptualised shows that the report lacks a strong public health lens.

Leaders of the Karnataka CHO union said they see themselves as mid-level health providers who can deliver primary care in areas without doctors and to elderly and vulnerable people who cannot travel to primary health centres. In contrast, from the state’s public health perspective, CHOs are viewed mainly as an additional cadre of multipurpose workers to implement vertical health programmes.

This way of thinking informed a recent government proposal, based on a study by the Boston Consulting Group, which suggested that for “efficiency” Arogya Kendras need not have both a CHO and a PHCO. Fortunately, this proposal was put on hold in May 2025, and the decision was taken to recruit all remaining CHOs.

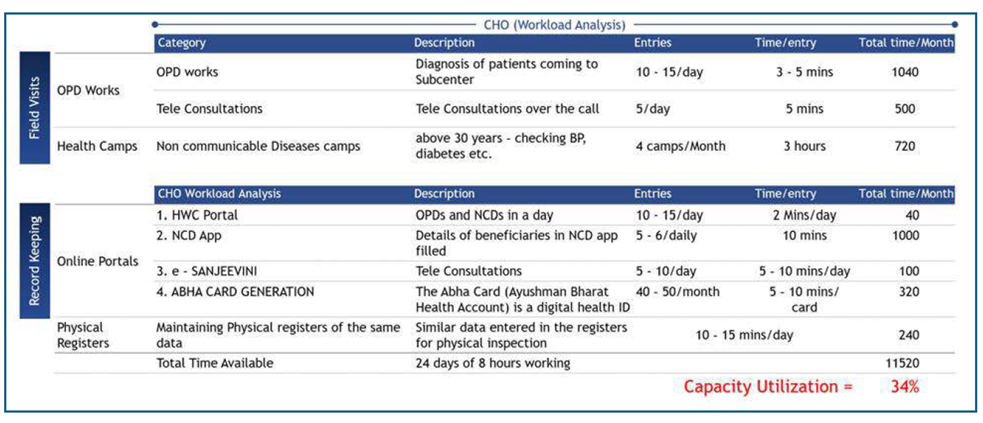

According to the study, CHOs are currently working at only 30–35% of their capacity, PHCOs at 90–100%, and Health Inspection Officers at 50–55%. The report recommended repurposing the CHO role by either posting them to primary health centres or assigning them additional data-entry work.

A closer look at the way workload and recommendations are conceptualised shows that the report lacks a strong public health lens. It treats primary healthcare largely as an expenditure item rather than as a way to realise people’s health rights. For example, it recommends hiring 3,000–3,500 PHCOs on contractual terms, with a salary of Rs. 14,000 instead of Rs. 40,000 for regular posts, in order to fill vacancies and cut costs. The focus should instead be on “lives saved, diseases prevented, and people’s health protected”, not merely on money saved.

The study reports that CHOs see only 10–15 patients a day, while primary health centres handle more than 200 patients, and concludes that people prefer primary health centres for clinical services. Even if these numbers are correct, the explanations and recommendations are overly simplistic. People can only develop trust in Arogya Kendras if CHOs are consistently available. However, because they are frequently deputed to work at primary health centres or placed in charge of other Arogya Kendras, they cannot maintain regular availability.

In addition, many CHOs reported shortages of medicines and equipment, including basic items such as paracetamol, antibiotics, anti-hypertensive and anti-diabetic drugs, and ointments for wounds. These gaps cause people to drop out of care and instead seek treatment in private facilities or at primary health centres, often travelling longer distances and spending more. Patient footfall for clinical services at Arogya Kendras could increase substantially if vacancies were filled and CHOs were supplied with the medicines they need to do their work.

In addition, the work of a primary care team leader—who builds team culture and a caring environment—cannot meaningfully be measured in minutes.

If the workload analysis (see figure) is interpreted with CHOs as key primary care providers and leaders of Arogya Kendra teams, it becomes clear that the activity list and time allocations do not reflect the realities of comprehensive primary care. Allowing only three to five minutes for each outpatient consultation is unrealistic, given that primary care rests on personal connection, long-term relationships, and trust.

Many activities that CHOs routinely perform to safeguard people’s health are missing from the analysis. These include home visits for elderly and palliative care, work with PHCOs and other staff to implement national health programmes (such as routine immunisation and the reproductive and child health programme), ensuring continuity of care, participating in review meetings, and holding regular meetings in the community and at the primary health centre. CHOs are also responsible for implementing any new programme introduced by the state. In addition, the work of a primary care team leader—who builds team culture and a caring environment—cannot meaningfully be measured in minutes.

The study also defines “closer to the communities” as a 30-minute travel distance from the Arogya Kendra or a radius of 10–15 kilometres. This ignores the practical reality that people must spend time and money travelling long distances even for basic primary care, and that logistics are far more challenging in hilly and tribal areas. Using examples from only three taluks and relying on unscientific population projections, the authors estimate that Karnataka could reduce the number of Arogya Kendras by 10–15%. As a matter of fact, there is a clear opportunity to strengthen existing Arogya Kendras, not to reduce their number.

Figure 1: From the Boston Consulting Group report “Unlocking State Budget Potential”, November 2024

Enabling Leadership

With the introduction of the CHO cadre, the scope of clinical care has expanded. People reported satisfaction that the CHO visits their homes when an elderly person needs care. Other staff members, especially PHCOs and ASHAs, felt better supported in sharing responsibilities and delivering services. In centres with more reliable drug supplies, service use increased and people felt comfortable relying on CHOs and Arogya Kendras for minor ailments and for follow-up of diabetes and hypertension.

Staff observed that earlier it was mostly women who accessed care, but now more men and elderly people are also coming to the facilities. Much more needs to be done to strengthen the potential of CHOs to serve as primary care providers closest to people’s homes.

CHOs have immense potential to transform primary healthcare in India, but this can only be realised through deliberate investment, trust, and systemic reform.

Many CHOs reported needing greater autonomy to manage clinical care and to mobilise the resources required for it. They also described a lack of supportive supervision within the system, with excessive emphasis instead on indicators and incentive payments.

Capacity-building efforts should not focus only on implementing vertical health programmes but also on empowering staff to provide holistic care, in line with what Indian Public Health Standards state: “Special attention should be paid to training of CHO at the HWC-SHC as he/she not only serves as the lead of the HWC-SHC and a clinician but has to look after the overall health of the communities.”

CHOs have immense potential to transform primary healthcare in India, but this can only be realised through deliberate investment, trust, and systemic reform. Strengthening primary healthcare through Arogya Kendras is identified as a priority for the Indian Council of Medical Research–Department of Health Research, which has also highlighted the need for implementation research to support this goal.

The system must therefore invest in learning how to improve, rather than continuing to under-invest. There is an urgent need to fill existing vacancies across all primary healthcare cadres, regularise posts, and ensure fair and timely compensation in every state. A system that depends so deeply on human connection and continuity of care cannot be sustained through contractual and short-term arrangements. Strengthening Ayushman Arogya Kendras through such systemic commitment is the only way to realise the vision of comprehensive, people-centred primary healthcare.

Swathi S. Balachandra is an Honorary Associate, Institute of Public Health Bengaluru, and Public Health Practitioner, Action for Equity, Bengaluru; Vaibhav Agavane is a Fellow and Assistant Professor, Institute of Public Health Bengaluru; Navya M S. and Padmavathi are Junior Research Associates, Institute of Public Health Bengaluru; and Prashanth N. Srinivas is the Director and Senior Fellow, Institute of Public Health Bengaluru.

Acknowledgement: We express our sincere gratitude to all the frontline health workers who generously shared their experiences and insights. We also thank the leaders of the Akhila Karnataka State Community Health NHM Contractual Employees Union for candidly describing their struggles and perspectives.