On 20 May 2025, the World Health Assembly (WHA), which is the world's highest health policy setting body that includes health ministers of all member states of the World Health Organization (WHO ), formally adopted the WHO Pandemic Agreement.

Discussions on a Pandemic Agreement were initiated at the WHO in May 2021 to correct the inequities that emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic and must be addressed for the future. The pandemic saw over 700 million confirmed cases and 7 million reported deaths, both likely to be underestimates, caused by a virus that went around the globe, mutated frequently, and has now become endemic. About 400 million people worldwide have experienced Long Covid, a multisystem disorder that can often be debilitating, and which is estimated to yield annual losses of approximately $1 trillion – equivalent to about 1% of the global economy (Al-Aly et. al. 2024) .

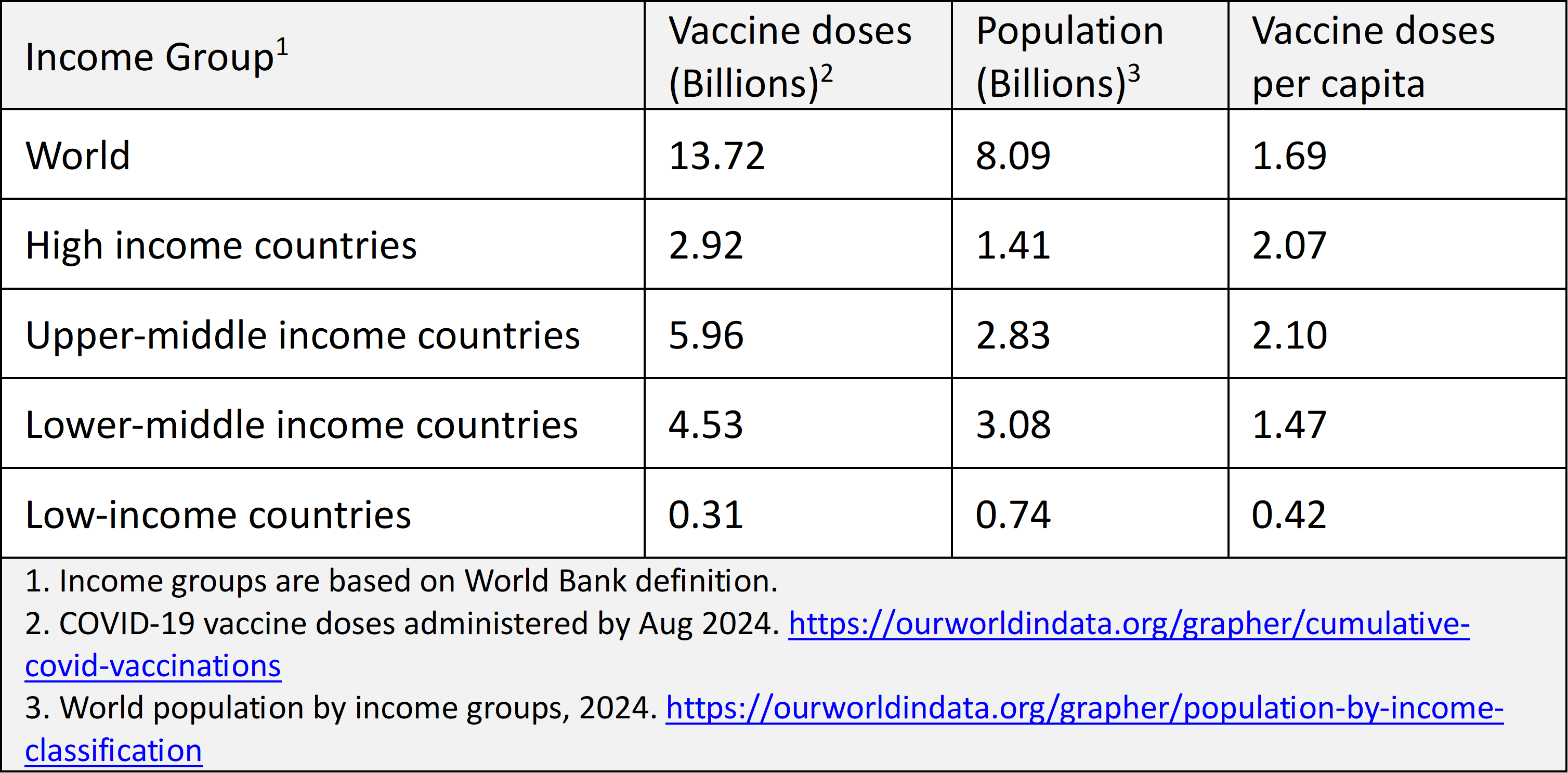

The rapid development and deployment of vaccines during the pandemic is estimated to have saved between 14 million and 20 million lives in just their first year of use (Watson et al, 2022) . However, these life-saving vaccines were not equally accessible to all (Table 1). High- and upper-middle income countries managed to administer on average over two doses per person, which was sufficient for protection from severe disease and mortality. Low-income countries could administer only about 0.4 doses per capita and Africa managed to get only 875 million vaccine doses for its population of 1.48 billion (0.59 doses per capita) – both woefully inadequate for immune protection.

An additional 157,000 Covid-19 deaths could have been averted in low- and low-and-middle-income countries if only 20% of the WHO vaccination target had been achieved by each country by the end of 2021. Had 40% of the target been met by each country in these economies, an additional 547,000 of deaths could have been averted (ibid).

Table 1. Global COVID-19 vaccine inequity

Vaccines are crucial tools for controlling infectious diseases. Their equitable distribution is important to effectively ending a pandemic, as it reduces transmission, prevents the emergence of new variants, and attenuates the burden on healthcare systems. The Pandemic Agreement is primarily aimed at sharing information and addressing inequities in vaccine access towards improving global pandemic preparedness.

History and timeline

The 73rd WHA held on 18–19 May 2020, requested the Director General of WHO to initiate an impartial, independent and comprehensive evaluation of the international health response to COVID-19. The Independent Panel on Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response (IPPPR) set up for this purpose issued its report: “Covid-19: Make it the Last Pandemic” in September 2020 . The 74th World Health Assembly meeting later that month established the Working Group on Strengthening WHO Preparedness and Response to health emergencies (WGPR). In November 2021, the WGPR report led the WHA to establish an Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) tasked with drafting and negotiating “a WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic preparedness and response.” The result of INB’s work is the Pandemic Agreement.

The PABS system would be a major improvement over the status quo, which witnessed vaccines stockpiled by rich countries instead of the vaccines going where they were most needed.

In its March 2024 draft the INB highlighted several articles that required commitments from WHO member states. Though there was broad agreement on the need to improve preparedness and promote international cooperation, there were disagreements around common but differentiated responsibilities (a term borrowed from the UN Climate Accord), which placed greater obligations on rich countries. To allow more time to negotiate and resolve those differences, member states delayed vote at the 77th WHA held in May 2024 for another year. An iterative process of consultations and drafts led to the WHO Pandemic Agreement that was adopted by the 78th WHA.

Going forward, negotiators have one year to work out details of the Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing (PABS) System, which remains the most contentious and still unresolved issue, and was moved as an annex to the Agreement. Once the PABS annex is adopted at the 79th WHA in May 2026, the WHO Pandemic Agreement will be open to signatures. One month after its ratification by 60 WHO member states, it will enter into force as a global Pandemic Treaty.

Key components

The main objective of the WHO Pandemic Agreement is to prevent, prepare for, and respond to pandemics. The agreement is guided by principles of equity, human rights, and international cooperation, with decision-making guided by the best available science. The provisions apply during and between pandemics, ensuring continuous preparedness while addressing health systems disparities and capacities among countries. The agreement emphasises strengthening pandemic prevention and surveillance, enhancing health systems resilience and regulatory systems, increasing collaborations in research and development. its central aim is to improve access to pandemic products through sustainable local production aided by equitable and efficient technology transfer.

1. Reducing Spillover Risks

The agreement outlines measures to minimise the risk of pathogens spilling over from animals to humans by enhancing surveillance, using a One Health approach and strengthening national pandemic prevention plans, including workforce training. Recognising the impact of environmental and social factors on pandemic risks, the agreement calls for collaboration across sectors to address drivers of infectious diseases.

2. Strengthening Regulatory Protocols for Drugs and Vaccines

Parties to the agreement are required to enhance their regulatory systems to ensure the quality and safety of pandemic-related health products. This includes expedited reviews and effective monitoring systems, established emergency authorisation processes, increased transparency and public sharing of information. Collaboration with the WHO to improve regulatory processes is also encouraged.

3. Protecting Health Workers

The agreement calls for countries to enhance and safeguard the workforce to be able to effectively respond to health emergencies while ensuring the maintenance of essential health services. This includes measures to ensure suitable working conditions, eliminating inequalities, and supporting mental health and well-being. The document lays down broad guidelines, but does not provide specific details on how these should be accomplished. A one-size-fits-all approach may not be very effective due to prevailing socioeconomic and cultural differences between countries and regions.

4. Technology Transfer

The Pandemic Agreement has significant technology transfer implications, particularly for developing countries seeking greater self-reliance in producing drugs and vaccines. Technology transfer involves sharing the knowledge and resources needed to locally produce drugs and vaccines, which could reduce dependency on pharmaceutical companies in developed countries. The agreement affirms that technology transfer should be promoted through licencing and capacity-building, enhancing the availability of licences for health technologies with “reasonable” royalties during emergencies. The support for local companies in developing countries is considered critical, and cooperation with the WHO is encouraged.

The agreement's language on technology transfer is contentious. Early drafts included the phrase "on mutually agreed terms," but some countries pushed for adding "voluntary," which raised concerns about setting a precedent for future agreements. In the final compromise, the treaty retained "mutually agreed terms" with a footnote defining it as "willingly undertaken’ ( footnote 8 of Article 4 of the Pandemic Agreement, on page 13). Though the framework is a step forward, it lacks hard obligations, leaving the effectiveness of technology transfer dependent on voluntary cooperation from pharmaceutical companies and the developed countries in which they are located. This wording avoids mandatory obligations, which some view as a missed opportunity to enforce stronger commitments, potentially limiting its impact on global health equity.

5. Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing (PABS) System

The PABS is a framework designed to facilitate the sharing of information about pathogens, enabling tracking their evolution worldwide. The agreement recognises the “sovereign right of States” over their biological resources and the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits. The PABS Instrument referred all parties to ensure “rapid and timely sharing of PABS Materials and Sequence Information and, on an equal footing, the rapid, timely, fair and equitable sharing of benefits, both monetary and non-monetary, including annual monetary contributions, vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics arising from the sharing and/or utilization of PABS Materials and Sequence” (Article 12, Clause 5(a) of the Pandemic Agreement, page 21). Under the adopted agreement, manufacturers of pandemic products committed to donating 10% of their production to the WHO and offering another 10% at affordable prices. However, several issues have remained unresolved, and are deferred for future discussions and drafting of the PABS annexe by a group of experts over the next year.

6. Framework for Future Collaboration

The Pandemic Agreement encourages cooperation to strengthen pandemic preparedness, particularly for developing countries, through technology transfer and capacity-building. Collaborations with international organisations are seen to be essential for effective support. Establishing the guidelines for international cooperation during future pandemics, information sharing on emerging pathogens, embracing the Global Supply Chain Logistics Network to ensure equitable access to pandemic-related health products during emergencies, and finding sustainable and predictable financing are seen as crucial to the success of the agreement.

Concerns and key challenges

The Pandemic Agreement had overwhelming support at the 78th WHA, passing by a vote of 124 countries in favour, 11 abstentions and zero objections. But some countries expressed concern. Of the countries that abstained, including Iran, Israel, Italy, Poland, Russia and Slovakia, the concerns were different and often at odds with each other . While Poland could not support the agreement ahead of a domestic review, Russia was concerned about country sovereignty, and Iran found the agreement to inadequately address key concerns of developing countries – pointing to the lack of binding commitments on technology transfer and pandemic products.

When the US stays away from the high table of global public health, it’s not just US children and adults who are at the mercy of emerging as well as vaccine preventable diseases. The entire world pays the price.

Implementation of the PABS system in the Pandemic Agreement remains a cause for concern. The operational details of how the PABS system will work, including how databases will be set up to ensure rapid access to pathogen information while tracking how companies use the data is one concern. The other is a consensus on vaccine and drug set-asides, with several countries calling the manufacturers’ non-binding commitment clause to be inadequate.

The draft PABS system has faced criticism with the British medical journal Lancet calling the proposal to make 20 percent of pandemic healthcare products available to low- and middle-income countries as “shameful, unjust, and inequitable.” Still, the PABS system, as proposed, would be a major improvement over the status quo, which witnessed Covid-19 vaccines stockpiled by rich countries instead of the vaccines going where they were most needed.

Resolving disputes and finalising the PABS annex in the approved Pandemic Agreement remains an immediate challenge. An early proposal to hasten consensus is to establish a group of independent experts to draft the PABS annex, which can then be adopted at the 79th WHA in May 2026. These concerns and challenges highlight the complexity of creating a system that balances equitable access with the interests of pharmaceutical companies and member states.

If you are not at the table …

The United States of America decided not to participate in the final vote at the 78th WHA, after Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. denounced the WHO for having “doubled down with the Pandemic Agreement which will lock in all of the dysfunction of the WHO pandemic response.”

The US position seems to emanate from two parallel lines of thinking. President Donald Trump’s first executive order in his second term notified US withdrawal from WHO “due to the organization’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic […] and other global health crises, its failure to adopt urgently needed reforms, and its inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states.” Additionally, a 2023 report Why the U.S. Should Oppose the New Draft WHO Pandemic Treaty, by The Heritage Foundation, a prominent American conservative think tank in Washington DC, accused the WHO of complicity with China and mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the draft treaty to focus on “expanding WHO power, trampling intellectual property rights, and “equitably” redistributing knowledge, technology, and other resources.”

Declining investments and participation in the WHO, together with contraction of other international health initiatives, such as USAID, pose a significant challenge for global health.

Does the Pandemic Agreement give the WHO power over national governments?

It doesn’t. The agreement specifically affirms national sovereignty in public health matters and does not give WHO the authority to direct, order or prescribe policies or laws when it comes to tackling future pandemics. For example, the WHO can only advise and has no authority to impose lockdowns or travel bans or mandate vaccination or testing campaigns. The US Intelligence Community remains divided on the most likely origin of COVID-19. All agencies assess that two hypotheses are plausible: natural exposure to an infected animal and a ‘lab leak’, with broad agreement that the virus was not developed as a biological weapon or genetically engineered or that China had any foreknowledge of it.

Pandemic amnesia and profiteering by protection of intellectual property rights of US companies even during a pandemic seems to be the real reason for this hostility. Despite its biomedical and pharmaceutical prowess, USA had the highest numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases (about 112 million) and deaths (1.2 million). Data show that when Covid-19 vaccines became available, excess death rates were higher amongst Republican voters compared to Democrats, primarily due to lower vaccination rates amongst the former (Wallace et al 2023). The rhetoric from Trump 2.0 appears to be lowering the confidence in vaccines, leading to reducing vaccination rates and the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles.

If you are not at the table, you are on the menu. When the US stays away from the high table of global public health, it’s not just US children and adults who are at the mercy of emerging as well as vaccine preventable diseases. The entire world pays the price.

Epilogue

The Pandemic Agreement includes provisions to reduce the possibility of future disease spillovers and to limit novel pathogens from spreading beyond their area(s) of emergence. This will only be possible if there is expeditious and equitable access to key infectious disease research and the tools for prevention (diagnostics, vaccines) and treatment (drugs). Much of this will require global cooperation, decentralised manufacturing, aligned regulation and novel financing models.

Global health has made great strides over the past 75 years. With an expected rise in emerging and re-emerging diseases due to climate change and human activities, treaties like the Pandemic Agreement will become even more important. Declining investments and participation in the WHO, together with contraction of other international health initiatives, such as USAID, pose a significant challenge for global health. Without international coordination, it will become harder to catch and address problems early enough to stop epidemics from becoming pandemics.

Shahid Jameel is the Sultan Qaboos bin Said Fellow at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies and a research fellow at Green Templeton College, University of Oxford.