In April, weeks into the Covid-19 lockdown, Rajesh 1 All names have been changed. , a migrant from Bihar working in the outskirts of Bangalore, contacted the Stranded Workers Action Network (SWAN). Sometime before the lockdown, he had cut his nose in a work accident. Now he despaired that rations had eluded him on account of the deficits of proof he possessed. 2 The One-Nation One Ration Card scheme allows beneficiaries to avail rations using the same ration card across states – 17 states and UTs were cited to have included themselves in this scheme. Atma Nirbhar Bharat free ration scheme was slated to provide 8 lakh tonne foodgrains to 8 crore migrant labourers – this was projected to be the estimated number of migrants who were not covered by the National Food Security Act or state PDS and would qualify for this scheme. Rajesh did not have any ration card and did not know about the Atma Nirbhar Bharat scheme.

To persuade us – faceless representatives of the relief network – of the forcefulness of his case as a disabled worker, he offered to send a photo of his injured face.

Migrant workers like Rajesh constantly offer up their personal narratives of debilitation and oppression to the government, the media, the police, donors, NGOs, filmmakers, volunteers, and social workers, in exchange for what is due to them as right. The lockdown following the onset of Covid-19 has exacerbated this lopsided relationship and made it starkly visible, inserting local struggles within complex inter-state, civil society-state and civil society-nation tussles and mandates.

Migrant workers ended up archiving much more than was required by these regimes, and became witnesses to unfolding violent truths.

The stranded migrants were anxious to simply have a chance to establish that they required assistance for themselves and their constituent groups. But as they encountered governmental and non-governmental figures who assisted them, they were thrown into a formal and an informal proof regime.

These proof regimes suspend migrant workers between what Deborah Poole (2004) terms “threat and guarantee.” It also belies any neat separation of relief work and policing, entitlement and atrocity, material and emotional evidence, the documentable and the unwritable. A month into the lockdown, workers were creating trails of paper, video and other artifacts, not merely to index their distress and lay claim to what was promised, but also to set up complex and paradoxical visual narratives of violence and gratitude. While the lockdown cast them within emotional, auditory and documentary regimes of making and producing proof, migrant workers ended up archiving much more than was required by these regimes, and became witnesses to unfolding violent truths.

The regimes of proof indexed so much more than what would have been agreeable to these official and unofficial figures. The ‘proof’ could be documentary artifacts of identity: online relief forms, SMSes, Whatsapp messages, bus and railway tickets, invoices, lists, or ID documents. Or it could be performative gestures and truth claims showing the migrant worker in real living time: the phone camera capturing the travelling worker on the bus or the train, the worker who has reached home, the shelter-based worker on the cusp of travelling.

Migrant workers anticipated violence, especially from government figures such as policemen […and] were invested in archiving relief work experiences that implicated these officials.

In this disturbing period also emerged the worker-turned-witness, who bore testimony to the violence and apathy experienced by their class 3 We are using a legal term here which implies a group of people with similar experiences and concerns. For example, one of the legal debates on Section 377 was whether homosexuals form a “class” that can then appeal that their fundamental rights are being violated on the basis of their being this class. Suresh Kumar Koushal & Anr vs Naz Foundation & Ors. Supreme Court of India judgement, 11 December 2013. , who collected evidence to prove wrongs done to them, and who turned reporter to show the world how they had been reduced to an existence devoid of dignity, self-respect, security and the smallest of comforts. Migrant workers anticipated violence, especially from government figures such as policemen, as opposed to NGOs and independent relief workers. The workers were invested in archiving experiences that implicated these officials.

In this article we draw on our experiences while volunteering with SWAN to think through these different forms and movements of proof, across myriad contexts of policing, official measures and relief work provisioning. We critique our own evidentiary practices, funding-related conventions, and ‘toolkits’ for assisting migrant workers, all in a neoliberal political environment.

The lockdown

Baees/22 March (the day of the 14 hour ‘voluntary’ lockdown) and Chaubees/24 March (the beginning of the longer nation-wide lockdown) are permanently imprinted in the minds of migrant workers as the hard date after which they could be certain of nothing. Companies, hotels and factories closed shop abruptly; contractors disappeared from the horizon; rations and food options contracted; and yet rent and other financial commitments continued to loom large. Within days the workers took to walking home.

To give an idea of the numbers of workers who needed support or relief, by 15 April, the 73 volunteers registered with SWAN had been contacted by 11,159 workers (roughly 640 groups of workers). By May this number trebled to 34,000 workers. More than Rs 50 lakh was transferred to workers’ accounts. In the two weeks to 1 June, over half of the 1,963 migrant workers who responded to SWAN’s Interactive Voice Response survey said they had no money or rations left and that they had missed their last meal. Even in early June, two-thirds of them had not been able to travel back to their hometowns. Of those who were still stranded, half said they wished to return home soon.

Migrant workers grappled with registration processes and websites that were not language-friendly or user-friendly.

What these figures do not reveal is the intense collective and individual struggles of stranded workers to register themselves online and in police stations, and to establish the urgency of their travel needs. To repeat what has been recorded already by SWAN volunteer-authors, migrant workers grappled with registration processes and websites that were not language-friendly or user-friendly. State websites for travel registration required migrants to establish themselves as phone owners who can receive OTPs, readers of English SMS-es, Aadhaar owners, ID owners and owners of photo-proof that met certain size and format specifications.

It was around this time that SWAN came into being. The network functioned to transfer small sums of money, arrange rations, and assist the workers with travel needs. In our personal capacities as SWAN’s South Zone members, we spoke to migrant workers who were based in the southern states (mostly Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh) and wanted to return to their home districts, mostly in Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal. We assessed cash, ration and travel needs of stranded workers, and arranged rations for them by connecting them with local organisations and individuals.

Among the tasks that SWAN performed was the documentation of workers’ information, that allowed different volunteers to act in concert to process requests and coordinate relief. Relief workers and organisations recorded names, phone numbers that could generate OTPs, number of men, women and children in each family, and bank account numbers, to enable accountability in funding channels. While SWAN did not ask migrant workers to submit Aadhaar details, volunteers had to nevertheless occasionally collect them when websites, government agencies and funders demanded them. This was ‘proof’ that the workers existed, were citizens and needed support. On the other hand, relief workers did not have to go through elaborate channels or great lengths to prove their bonafide credentials to migrant workers or the government to start volunteering.

Technologies and audits that place a heavy premium on transparency can be blind to their own shifting definitions of what constitutes proof.

Anthropologists like Laura Bear and Nayanika Mathur have described how transparency, accountability, and fiscal discipline can present themselves as public goods through an emphasis on technocratic and technical procedures. But they indicate these 'neutral' principles are entrenched in the form of utopian goalposts of a bureaucracy. This is all the more so in neoliberal spaces where funding is tied to targeted spending. Technologies and audits that place a heavy premium on transparency can be blind to their own shifting definitions of what constitutes proof, and sometimes, the very implausibility of presenting it (Bear and Mathur 2015: 21).

That these institutional aspirations grated on the nerves of the workers was clear in one instance, when we called a group of workers in Tambaram, Chennai. They were in need of assistance to travel back to West Bengal but had clearly lost faith in the systems that were supposed to ensure that this happened. They told us in no clear terms that they did not want to send their ID documents to us till they were assured that it would result in substantial and visible assistance. It was only when we told them that we had a funder who was ready to book flight tickets for them that they relented and sent us the documents.

Sometimes, much more than submitting bureaucratic evidence of one’s self was required: the worker also had to access circuits of power. The experiences of Jitan and Sanjay (father and son) are telling. On 31 May, they were illegally evicted by the company they were working for in Pollachi taluk (Coimbatore district) and told to go to Coimbatore city where they would be able to catch a train back to East Champaran in Bihar. They ended up on the platform outside the Coimbatore railway station with no food, money or means of discovering how to catch this promised train. After they were guided to a Corporation-run shelter, efforts were made to get them tokens to board the next train to Bihar. Their names had been registered on Tamil Nadu’s Covid 19 Prevention and Rescue app and they had all their identity documents, but this was evidently not enough. They received no messages and could not gain any information through this registration.

It was only after a harrowing two days, and after we contacted local volunteers and a helpful local journalist, that Jitan and Sanjay were able to get some direction on what could be done. They eventually had to go to the secretary of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions in Coimbatore, who then managed to immediately assign them tokens from the quota assigned to him. It was only the constant replaying of the fact that one of them was a senior citizen, within the narrative of eviction and homelessness, that secured them support.

No proof they had of their identity was valid, until ‘other’ kinds of authority stepped in.

Witnesses to violence

When it came to travel, the workers had to follow up their online site registration with visits to the local police station where they were, either independently or on the basis of the post-registration SMSes, included in police lists of those who could board shramik trains. Police stations became processing centres for migrant travel, with each police station being given quotas to fulfill. Migrants had to wait to receive information of the shramik train schedule and their seats on it.

We came across a disturbing number of workers who put a fine point on their repeated visits to police stations as resulting in abuse, slurs (even communal, especially in the case of West Bengal Muslim migrants in Karnataka), lathicharges, and threats of imposition of Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

The police ended blurring their law and order roles with relief ones while working to ensure relief and facilitating travel for migrant workers.

In his conversation with one of us, Sunil, a Jharkhand-based migrant worker in Karnataka, narrated a collective experience of a group of nine daily-wage labourers who were working to fit tiles in a newly built house in Kadaba, Mangalore district.

The lockdown had blocked-up the finances of the house owner, and he couldn’t pay this group the 50,000 rupees he collectively owed the workers. A week into the lockdown, the stranded workers were desperate to find rations, but had run out of cash. They were cramped together into a 10 feet by 12 feet hall, where more workers freshly out of jobs were joining them. If this intensified their craving to go home, they found themselves at an impasse caused by all manner of bureaucratic battles with authorities.

“You see, multiple permissions were required from the tehsil office, the local panchayat, and the thana,” Sunil explained.

When a train scheduled in May for them got cancelled, they protested outside the tehsil office to be given permission to go to Udupi, about 136 km away, from where the police were arranging for migrants to catch another train scheduled to leave for Jharkhand. The police threatened to arrest Sunil's group if they leave for Udupi on their own, and lathicharged them.

It took no time for the police to turn this relief function into a policing one and seal this border between Kadaba and Udupi, even if these men were no infiltrators. Sunil stressed that he had “all types of proof” – of course he could not prove the lathicharge, but he remembered and noted down the day this took place, knowing that this alone might not add up to much.

Pooja Satyogi, an anthropologist who studies policing as labour, shows in her work that the official work role of the civilian police force in India is often inaccurately assumed to be only enforcing law and order. The police have in the past been responsible for an assortment of relief-related work, including disaster-related rescue efforts. It is unsurprising, though, that the police ended blurring their law and order roles with relief ones while working to ensure relief and facilitating travel for migrant workers.

But this type of violent policing was not the only thing to record or prove.

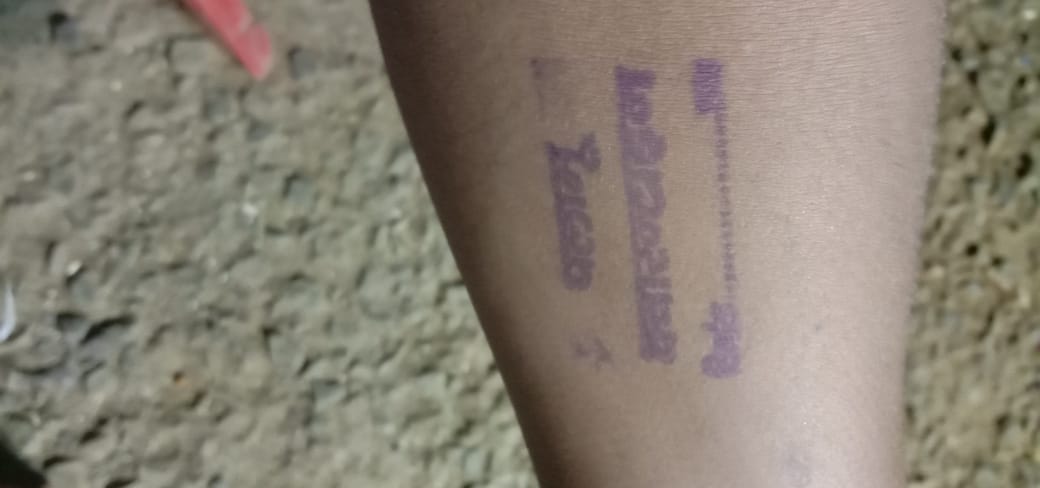

When Sunil’s group was finally given permission to travel to Nelamangala train station, 285 km away, they were asked to pay 930 rupees as the train ticket fare. The Karnataka government had decided to collect train fares from migrant workers despite contrary orders from the railway ministry and the Karnataka High Court. 4 Ministry of Railways order, 2 May 2020. Karnataka High Court Daily Order Case No. WP 6435/2020,12 May 2020. Some states had agreed to bear train fares of migrant workers who are returning to their home districts. Sunil took photos of this ticket because he felt instinctively that the state was asking him to pay for an entitlement. When they were allowed onto the sleeper train, they were seated in a separate bogie where there was no place to sleep. Sunil sent one of us screenshots of Whatsapp messages he exchanged with a police official, as evidence of a railway ticket that did not even do what other tickets did: provide a place to sleep on the train. 5 The migrant also bitterly complained that they were not provided proper food. The police official told the migrant that railway food and the absence of sleeper seats were not their responsibility as they fell into the jurisdiction of the revenue department and the railways.

This evidence presented by migrants must be read against the evidence advanced by Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, who presented the government’s case in the Supreme Court.

Hemant, another worker, explained to us how his group left their jobs at a Bangalore government-owned building company that owed the workers a huge sum of money in unpaid salaries for February and March. They decided to go back home to Jharkhand. Even after they had registered on Karnataka’s Seva Sindhu site and paid Rs 930 to travel they were stopped by policemen who interrogated them and at one point lathicharged them. Between 5 May and 15 May, they were moved from one shelter to another until they could finally leave. The workers took photos of the various shelters they were abandoned at to underscore that they had been wronged and to flag that they were unsure if they would ever be allowed to leave.

In this and several other instances, migrant workers conveyed that police violence and state apathy were not smoothly archivable. And yet they were keen on documenting whatever was adjacent evidence to a significant truth: dates to record lathicharges, tickets that didn’t yield what they were supposed to, photos of multiple shelters which stood in for belated entitlement, photos of the sparse chips and biscuit packets they were served as ‘food’ on the Shramik trains. This evidence presented by migrants must be read against the evidence advanced by Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, who presented the government’s case in the Supreme Court by arguing that an inquiry had found no deaths had occurred on shramik trains on account of lack of food and water. 6 Newspaper reports announced that 80 deaths had occurred, in the month of May alone, before, during or after travel on Shramik trains – including 35 year old Avreena Khatoon, a young mother who died on the platform in Muzaffarpur (Bihar); four and a half year old Ishtaq, who also died at the railway station Muzaffarpur; and Divyang Dashrath, a 30 year old man who was found dead when the train reached Manduadih station (Varanasi). In all these cases relative and other sources quoted in the news reports alleged that extreme heat, starvation and thirst had led to these deaths. This stands starkly in opposition to the government inquiry which declared that in all cases the people who had died had been chronically ill or had comorbidities.

In some other instances, evidence collected by workers took the form of interviews with newspapers and news channels, where they spoke a longer pattern of threats, indifference and intimidation from multiple authorities when they sought to go home. They also shot videos (with narrative included) of the large crowds gathered at railway stations and temporary shelters, and the deplorable conditions in the large community halls they were made to wait in for their trains. They gathered all this evidence in the full knowledge that there might well be no judicial forum that was necessarily interested in this small scale of intensity of violence or in challenging police immunity. 7 A quick review of court cases that address migrant worker needs and concerns shows that though, in general, the courts seem to insist that states step in and do the needful to ensure the welfare of workers, they simultaneously rely on certain forms of evidence to be satisfied that these requirements are being met. They review the status reports submitted by governments, listen to the testimonies of government officials and review the Standard Operating Procedure put in place by the central government. One writ petition filed by advocate Alakh Alok Srivastava, seeking redressal of the grievances of migrant labourers in different parts of the country, resulted in the Supreme Court declaring that based on the government’s status report, all measures seemed to have been taken to stop mass migration. The judges also decided that the real threat was fake news that triggered this migration, and cited Section 54 of the Disaster Management Act, which prohibits circulation of false information that leads to panic.

Grief and gratitude

In the still-unfolding scenario, what has been widely noted is that NGOs did more to help migrants than state governments did. This said, funding-related cultures of documentation have made it imperative for organisations to establish that there has been no departure from dictums of performing relief work. Social activists and relief workers such as us were equally complicit in this process of documentation, enumeration, and the offering up of ‘proof’.

There is something to be considered further in how social justice agendas are shaped by funding circuits and the expectations of donors.

George Marcus as well as authors of the ground-breaking volume Documents: Artifacts of Modern Knowledge, edited by anthropologist Annelise Riles, have argued that there is a remarkable affinity between the filing, documenting and cross-referencing practices of bureaucrats and those of university offices, research organizations, accounting firms (Marcus, cited in Riles 2006: 7) and in this context, NGOs and relief workers. In India, the circuits of international and national funding and the apparatus they establish around the notion of accountability ensure that activists and social workers within formal organisations are forced to account for the good that they have done, and show change. The more institutionalised the social justice work, the more embedded it necessarily becomes in this regime of ‘proving’ change.

While there is nothing inherently problematic in the idea of accountability, there is something to be considered further in how social justice agendas are shaped by funding circuits and the expectations of donors.

As the feminist scholar Wendy Brown (2016) indicates, this is all the more true in our contemporary neoliberal political sphere where every conceivable type of right has its place only in a market democracy. Collectively inhabiting such a sphere, NGOs, relief workers and government actors alike must engage in scrupulous audits that individuate the migrant worker, or in other words, mark out every individual as responsible for the costs she incurs on paper.

This is done through reports that include narrative statements, detailed lists of beneficiaries, photographs, written and visual testimonies, progress reports, process documentation notes, impact assessment tools and, of course, excruciatingly detailed financial accounts. The Indian government’s recent crackdown on NGOs has also meant a tightening of surveillance nets and taxation regimes around any social justice related work in the country. In other words, there is little alternative but to comply with the processes that the state and private or corporate parties have established as a public good, in this case, a normative and legalised measure of accountability 8 The Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2020, passed in the Parliament in September, has rendered the survival of NGOs more uncertain and threatens to increase surveillance on what funding is utilised for. .

We pose a question here on what accountability would look like if located completely in these workers’ narratives and testimonies, instead of in collected documents of proof.

The flow of accountability is then forced to turn towards the state or private funders, rather than towards the “beneficiaries” of such support (however much care goes into the work that is done). We pose a question here on what accountability would look like if located completely in these workers’ narratives and testimonies, instead of in collected documents of proof, lists of registered names, and official narratives offered up by the state and funders or intermediaries.

In the process of complying with these processes, NGOs and relief networks are often unable to account for the disparate needs of collective entities behind the individual spokesmen and representatives. As SWAN workers we were unable to inquire into the internal caste and religious dynamics of migrant workers’ groups, or the gendered hierarchies of families, when we made small transfers of money on the assumption that each individual was entitled to 400 rupees.

During this period, many organisations and individuals who participated tirelessly in relief work had to replicate state methods and exceed them. This labour of evidencing mandated all this and more: enumerate worker communities according to region, area, or state; rank and prioritise people and communities according to definitional hierarchies of migrant workers’ needs; collect copies of ID proof; gather worker testimonies; compile lists of rations delivered; prepare invoices for all donations; and prove work accomplished through photos of workers on trains and of rations being delivered in real time. In some cases, certain funders also demanded that that social distancing be visibly embraced by migrants and volunteers – after all, it would not show any of us in a good light to momentarily lose sight of the lurking virus! In some instances, accompanying the paper trail and the enumerative lists were also videos of workers showing their gratitude for the rations received, and inscribing personalised messages expressing this.

Bureaucratic infrastructures and processes […] implicate migrant workers within multiple colliding regimes of proof beyond relations between the government and the citizen.

We do not at all wish to judge the efforts of relief workers all over the country or castigate them, our own teams at SWAN included. The point being made here is that during this time, when the movement from a dignified livelihood to destitution has been horrifyingly fast tracked, and a return home excruciatingly delayed, those who were previously working for a living and sending money home to their families have now had to accept 'free' rations and kindness from strangers, with no hope of repaying the amounts transferred or food given. 9 That this weighed on them is evidenced by the fact that many workers told us that they didn’t need rations anymore, once they regained access to some work. In so doing, they have had to mark and populate their gratitude at every turn – many workers sent messages and voice notes thanking us. In some instances we also received videos from relief workers who filmed the workers holding up signs that displayed hearts bearing our names along with the words ‘Thank You’. These are gestures that, while in every way well-meaning, carry the burden of the imbalance, deprivation and inequality that this moment has harshly brought to the fore.

Conclusion

Anthropologist William Mazzarella indicates that “the transparency machine” (Mazzarella 2006: 489) and an e-polity (that provides online interfaces for downloading, digitizing, transmitting, photographing, and videographing) forces the government and citizens to be “immediately present to each other” (Mazzarella 2006: 485). 10 Mazzarella was referring to the self-validating opacities of e-governance in assembling news, presenting televised stings as truths, but he hints that the same techno-practices present as ‘seductions’ are at work in a welfare polity that believes digitisable equals incorruptible as far as, for instance, land records are concerned. There are resonances of this in work by other urban anthropologists, Solomon J. Benjamin, R. Bhuvaneswari et al (2007) show that digitization of land records in Bangalore, far from making things transparent, only centralised corrupt practices and made them intractable. We argue that bureaucratic infrastructures and processes, both conventional and electronic, implicate migrant workers within multiple colliding regimes of proof beyond relations between the government and the citizen. The Malayalam film Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum illustrates a common conundrum of policemen as state officials, incentivised to rearrange written complaints such that they suit their bureaucratic pace and ease their paper burdens, even if all that they are attempting to solve is a chain-snatching crime.

Courts [...] are all too eager for paper truths that attest to a well-oiled state machine [... Migrant workers] must find a way to survive in the auditory cells of Excel sheets, case notes, reports, dynamic videos, and databases.

For the policemen who were trying to maintain a meticulous record of migrant departures, violence is justified if the worker seeks to upset the delicate balance between relief work and policing, or if their work exceeds the limits of what they can administratively interpret. Courts on the other hand, are all too eager for paper truths (Tarlo 2003: 62) that attest to a well-oiled state machine – judges intrinsically wish to believe a state that is savvy in affidavit writing and in the statistical, albeit shoddy, citation of its generous feats. Migrant workers are however implicated in a web far more intricate and criss-crossing than one of state making. They must find a way to survive in the auditory cells of Excel sheets, case notes, reports, dynamic videos, and databases within governmental and NGO ecosystems. Workers have however created their own “archival pact with the future” (Osborne 1999, Robertson 2009: 333) by recording events and capturing fragments of violence wherever and however they can. Even as they perform their grief and anger, they wish to narrate a semblance of their truth on their terms.