“India under Modi” is a much discussed subject. More than a decade has passed since Narendra Modi led the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to victory in the 2014 election. He has since led the party to two more terms in office, in 2019 and 2024, even though the BJP did not win enough seats to form a government on its own in the last election. In this long decade, India has changed in many ways. Some would say, changed beyond recognition.

The dominant story about this change, the one you hear on TV channels, is that India finally has a “muscular” leader who has “fixed” Kashmir (though the Pahalgam attack showed that to be an empty boast), put “anti-nationals”—read dissidents—in jail, made the country a better place, and given it a higher profile in the world. The other is of a Hindu majoritarian government with an authoritarian leader who brooks no criticism despite his lip service to the idea—not even from his own party members. He has never held a press conference, and those who oppose the government and its policies are labelled “terrorists”, “urban Naxals”, and “anti-national”.

Despite the accusatory labels the BJP and its cohorts might use for them, large sections of Indians are determined not to let their country fall hostage to Hindutva’s narrow vision of nation, nationalism, citizenship, and social hierarchy.

At the centre of the two opposed narratives is the question of identity—religious identity, caste identity, and increasingly, linguistic identity. The BJP and its backroom monitors, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), may woo Dalits and Pasmanda Muslims for electoral gains, and parade Modi as India’s first prime minister who belongs to the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). But try as it may, the BJP has been unable to shrug off its image as a promoter of an anti-Muslim, anti-Dalit, Brahmanical order. That is because, despite the accusatory labels the BJP and its cohorts might use for them, large sections of Indians are determined not to let their country fall hostage to Hindutva’s narrow vision of nation, nationalism, citizenship, and social hierarchy.

But it is an unequal battle. Three new books lay out in alarming detail how deeply Hindutva leverages every instrument of power—the BJP’s political dominance, state machinery, the judiciary, the Election Commission, Aadhaar’s surveillance capabilities, the police, and national investigative agencies—to silence, marginalise, and demonise dissenters. Their playbook even normalises eliminating “inconvenient” voices to enforce their supremacist vision.

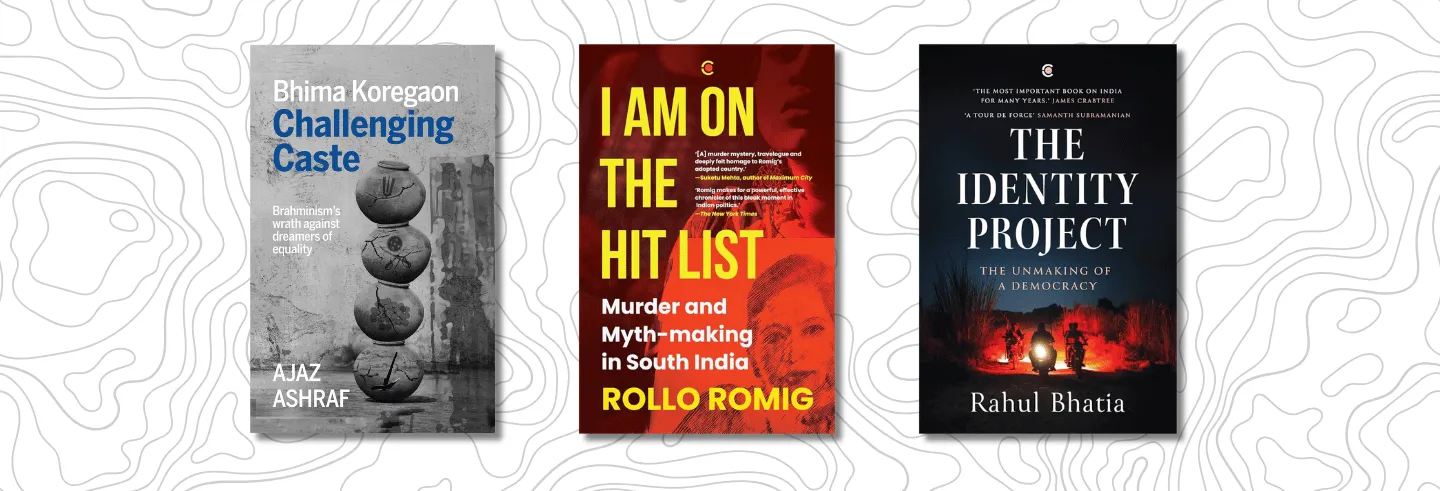

The three books—Bhima Koregaon – Challenging Caste by Ajaz Ashraf; I Am On The Hit List – Murder and Myth-Making in South India by Rollo Romig; and The Identity Project – The Unmaking of a Democracy by Rahul Bhatia—tackle three apparently different subjects, but an underlying theme connects them. Think of them as three episodes of Hindutva versus the People Who Won’t Fall in Line.

Bhima Koregaon

The first is a deep dive into the violence of 1 January 2018 at Bhima Koregaon, a memorial on the outskirts of Pune to the Mahar soldiers in the British army. It commemorates the bravery of those who fought and won against the Peshwas at the site of the 1818 battle during the Third Anglo-Maratha War. Every year, thousands of Dalits gathered there to celebrate the anniversary of that victory over Peshwa rule.

The Maharashtra police—and later the National Investigation Agency (NIA)—investigated the violence that erupted on the 200th anniversary of that victory, arresting a group of academics and rights activists now known as the “BK16.” Branded as urban Naxals by the media and officials, they faced a judiciary willing to accept the agencies’ claims. Nine are free on bail after spending three to five years in prison, including during the Covid-19 pandemic. One detainee, Father Stan Swamy, died behind bars.

Ashraf’s examination produces a riveting and more convincing account of what actually happened in Bhima Koregaon. He writes about the “fight over history” at Vadhu Budruk, a village three kilometres away from Bhima Koregaon, where Shivaji’s son Sambhaji was cremated.

Ashraf says at the beginning that his is not a linear narrative but one with “digressions and detours, a sudden skip to the past and leap back to the present”. There are many twists and turns, but Ashraf made the right decision by addressing each issue as it arises. These include the history of Maratha rule, Shivaji’s low-caste origin, the rise of the Peshwas, the Peshwa-Dalit relationship, the rise of the Shiv Sena in the mid 20th century, the Mumbai textile mill workers’ strikes of the 1970s and 1980s driving people back to their villages, the demand that Marathas to be included in the list of OBCs, and the Maratha-Dalit conflict.

Each of these sub-stories in the book is told through events and characters, and they set the context for its central narrative—two episodes in the dying days of 2017 and one on the first day of 2018, and how investigators, seemingly with a fixed agenda, meticulously tried to link two of these to each other and to an alleged Maoist conspiracy aimed at overthrowing the democratic government, while burying the third incident. One chargesheet even connected an accused individual to a supposed plot to assassinate the prime minister.

Ashraf’s examination produces a riveting and more convincing account of what actually happened, starting with the first of the three events. He writes about the “fight over history” at Vadhu Budruk, a village three kilometres away from Bhima Koregaon, where Shivaji’s son Sambhaji was cremated. After Aurangzeb captured and tortured Sambhaji in 1689, his mutilated body was left at Vadhu. But who defied the emperor’s ban on last rites? On 28 December 2017, a plaque appeared outside the Sambhaji samadhi naming Govind Gopal Mahar as the person who cremated him It recounts how Mahar ignored Aurangzeb’s orders, gathered Sambhaji’s scattered remains, reassembled them, and conducted the cremation in the village of Maharwada. In gratitude for this courageous act, Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj I, the board claimed, granted Govind Gopal 45 bhigas of land.

The board, said to have been placed by a 10th generation descendant of Govind Gopal on the night of 27 December 2017, sought to correct the legend on another board in the samadhi that identified Shivale, of the Maratha caste, as Sambhaji’s cremator. This board had been placed in 2015, in place of another board that had existed there since 1960, which did not identify the cremator, but named Govind Gopal as one of the persons appointed for the upkeep of the garden around the samadhi.

Ashraf delves into the archives to come up with a new document that buttresses the claim of the Mahar family that their ancestor was Sambhaji’s cremator. The battle of the boards created tensions in the Maratha-dominated village and led to a massive mobilisation of Marathas from the entire region on 31 December 2017. The principal instigators of this mobilisation were the Hindutva leaders Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote. And it was these Marathas who travelled to the Bhima Koregaon memorial to challenge the Dalit gathering there, leading to rioting and the death of one person. Such violence had never before occurred at the annual event.

…Bhide was not arrested and his name was subsequently dropped from the case after Chief Minister Devendra Fandavis gave him a clean chit. Bhide counts Prime Minister Modi among his friends, and Modi refers to him as “guruji”.

Ashraf’s book makes the case that the violence in Bhima Koregaon was a fallout of the events at Vadhu Budruk, and not because of a Maoist conspiracy or the anti-Peshwai poetry recited at Elgar Parishad, the second in the chain of events, a large public meeting held in Pune on 31 December 2017 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the battle of Bhima Koregaon.

Twenty-five first information reports (FIRs) were filed by those present at Bhima Koregaon on 1 January 2018, including a police officer, accusing Bhide and Ekbote for the outbreak of violence. But Bhide was not arrested and his name was subsequently dropped from the case after Chief Minister Devendra Fandavis gave him a clean chit. Bhide counts Prime Minister Modi among his friends, and Modi refers to him as “guruji”. Among the most interesting pages in Ashraf’s book is a profile of the Muslim-baiting Bhide, a member of the RSS who now runs his own organisation called the Shiv Prathishthan Hindustan. Revealing interviews with two of his former associates who quit his organisation tell us how hate is spread systematically.

Ekbote spent a month in jail after stern orders to the police from the Supreme Court. But in contrast to the laissez faire attitude towards these two men, the police lost little time in finding a Maoist conspiracy involving the Elgar Parishad.

The case against the BK16 carried the bad odour of a vendetta against the government’s critics from the start, but locking them up in jail without any interest in bringing the case to trial served two purposes. One, there was no need to prove anything in court because the process itself became the punishment, and, two, it had a chilling effect on criticism and political dissent.

A lab in the US examined the cloned copy of computers belonging to two of the BK16, researcher Rona Wilson and lawyer Surendra Gadling, and concluded that their devices had been hacked to place incriminating material on them. “Bhima Koregaon displays Brahminism’s wrath and perdition awaiting the dreamers of equality,” observes Ashraf.

Hindutva’s Laboratory

Romig’s book brings an outsider’s eye to the murky goings-on in Karnataka, often known as a laboratory of Hindutva. He is not a complete outsider because what happens in Karnataka, or for that matter in India, is deeply personal to him. He is married to an Indian Muslim woman from Kerala and they have lived in Bengaluru for several years.

Romig could not hide his dismay when his father-in-law indicated that he was considering leaving the country. “He shocked me by saying he was thinking of emigrating. ‘You have to look over your shoulder every 15 minutes,’ he told me. ‘It’s intolerable to have to live on high alert just because you worship a different god’.” Romig writes that he was filled with dread on hearing about the troubles of India-based foreign journalists who wrote critical stories and feared that he might not be allowed back in the country after the publication of this book.

I am on the Hit List is about an incident that took place in Bengaluru four months before the Bhima Koregaon violence, and shook all progressive people who disagreed with the Modi government, the BJP, and Hindutva in general to the core. That incident was the assassination of Gauri Lankesh on her doorstep by two men on motorcycles, one of whom shot her down as she returned home from work on the evening of 5 September 2017.

In his deeply researched book, which includes scores of interviews and hundreds of pages of documents, including the FIR and the chargesheet in the case, Romig draws an intimate profile of Gauri. He shows how she changed from an English-speaking, P.G. Wodehouse-loving journalist who was known more for being a warm, friendly, and charming person than for her journalism, to the editor of Gauri Lankesh Patrike, in which she espoused Kannada nationalism, fierce secularism, and concern for the marginalised and oppressed, railing in free-style rhetoric against the rising tide of Hindutva.

After that [the anti-Muslim pogrom of 2002], Gauri Lankesh no longer felt bound by the rules of journalism, which she believed came in the way of doing the right thing and taking a position against the regression and repression taking place around her.

Family members and friends speak to him about her commitment to her work—from 2000 until her death, she wrote a weekly column without a break—and to her close-knit group of family and friends. After her initial heartbreak and grief, she remained friends with her ex-husband until the end. She sought out and struck friendships with young people who were being hounded by the BJP government—Jignesh Mevani, Omar Khalid, Shehla Rashid, and Kanhaiya Kumar—and mothered them.

A big element of Gauri’s transition was the anti-Muslim pogrom of 2002 in Gujarat under the watch of Modi, then the chief minister of the state. After that, she no longer felt bound by the rules of journalism, which she believed came in the way of doing the right thing and taking a position against the regression and repression taking place around her. Her lawyer recalls advising Gauri to be careful with her choice of words, and her breezy attitude to the cases that were piling up against her—“I’m going to call a scoundrel a scoundrel. It’s your job to defend me.”

Romig, who wrote a long read on Gauri’s killing for the New York Times earlier, takes us step by step through the slow but eventually fruitful investigation of the case and the arrests of her killers, including those involved in the conspiracy. While there were many theories about the motives of the killers, the investigation narrowed it down to a speech that she had made in 2016, questioning the basis of Hinduism as a religion. The clip of this speech, which she delivered in Kannada at an event of the Communal Harmony Forum, went viral in Hindutva circles.

Investigators concluded that she was killed by a small “assassination group” founded by a member of the Sanatan Sanstha, a Hindu nationalist group based in Goa. This group was also responsible for the murders of doctor-activist Narendra Dhabolkar, who was a campaigner for scientific temper and rationalism, in Pune; lawyer and Communist Party of India member Govind Pansare in Kolhapur; and scholar and rationalist M.M. Kalburgi in Dharwad. All these people were seen as representing big threats to Hinduism. In their geographical connectedness, Romig says the four murders are a straight arrow “penetrating deeper into south India with each killing”.

…[Romig] also steps back from the case to capture the fast-paced political, social, and cultural transitions taking place in Karnataka and India with the rise of the BJP as the country’s pre-dominant political party.

Romig writes that the police told Gauri’s family that she was “a great soul” because her death prevented others on the hit list of her assassins from getting killed. Who were the others? K.S. Bhagwan, an outspoken academic, who was also friends with Kalburgi, and had been denounced as a “heretic” by the Sanatan Sanstha; playwright, actor, and director Girish Karnad; and C.S. Dwarkanath, a lawyer and Ambedkarite who gave a lecture in Mangalore against building a Ram temple in Ayodhya.

The author also steps back from the case to capture the fast-paced political, social, and cultural transitions taking place in Karnataka and India with the rise of the BJP as the country’s pre-dominant political party. It provides the context in which Gauri’s murder takes place—religious intolerance, “hurt sentiments”, Muslim baiting, protests against amendments proposed to the citizenship law that sought to keep out Muslims, and restrictions on the press.

Despite the sometimes meandering narrative, which takes the reader to Kochi and Muziris and Chennai, where he earlier wrote about the owner of the famous Saravana Bhavan chain of restaurants who was convicted of murder, Romig is a powerful storyteller, and he chronicles Gauri’s story and captures the zeitgeist with accuracy and clarity.

Identity and Hate

Bhatia’s book opens in the India of more recent memory, with the protests against the proposed amendments to the citizenship laws, which excluded Muslims from other countries seeking citizenship in India, but offered this privilege to Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, and Jains from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. In one fell swoop, the proposed amendments (now part of the citizenship legislation) seemed to imply a problem with Islamic countries in India’s neighbourhood, and signalled to Muslims in India that they too were unwanted.

That feeling intensified as the National Register for Citizens got under way in Assam, leaving thousands of people who had lived their entire lives in the state anxious about their future. In February 2020, rioting targeting Muslims erupted in north-east Delhi, as punishment for the sit-in by Muslim women at Shaheen Bagh, near Jamia Milia University, against the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill.

Bhatia tracks down Muslims caught in that violent maelstrom. He finds an RSS man who runs a shakha in a wretched neighbourhood in east Delhi. He speaks to a Hindu family whose son was arrested for rioting. But Bhatia’s most interesting encounter is with a man in Kolkata in his late sixties called Partha Banerjee, who had been taken to his first shakha when he was just six years old by his father Jitendra. Then at 25, he left for America to do a doctorate. In the mid-1990s, when he realised that the RSS dream of a Hindu idea was about to come true, he decided to write a book. It was called In the Belly of the Beast: The Hindu Supremacist RSS and the BJP of India, An Insider’s Story (Ajanta Books International, 1998). It was a brutal takedown of the RSS.

Bhatia tells of how Aadhaar soon became a requirement for everything from getting a telephone SIM to starting a new business. Despite a court ruling that Aadhaar was not required to open a bank account, banks began insisting on it.

Bhatia also devotes a couple of chapters to Aadhaar and the “Identity Project”, with a detailed profile of Nandan Nilekani and his failed bid in 2014 to win from a Bengaluru Lok Sabha constituency as a Congress candidate. After Modi’s sweeping win in that election, Nilekani, apprehensive that the Unique Identification Number (UID) project would be shelved, hastened to Delhi and sought an audience with Modi. There he convinced Modi to make friends with Aadhaar, to see it as a weapon in his war against corruption. Modi, who had been a strong opponent earlier, was won over.

The prime minister now wanted to enrol a billion people as soon as possible. The first budget of the Modi government included a US$300 million allocation for the project, a huge rise over the previous year. Bhatia tells of how Aadhaar soon became a requirement for everything from getting a telephone SIM to starting a new business. Despite a court ruling that Aadhaar was not required to open a bank account, banks began insisting on it. Then it became mandatory for filing tax returns.

Bhatia says he too finally succumbed to getting himself ID’d by Aadhaar. He speaks for many of us when he writes about the angst at finally surrendering to the system. The process, including biometric data registration, felt like “something had been taken away by force, and there was no one to complain to”. He notes that compared to his repulsion, few others were troubled by it. “For most ... it was just another thing to accept, and they moved on. When orders came from ‘above’, that catchword for a mysterious authority, the only realistic course ... was to fall in line.”

He also writes of how few knew it was first advanced as an internal security tool by L.K. Advani, home minister in the Atal Behari Vajpayee government. “People whose business it was to think of rights and transgressions worried about its potential to cause damage they could only imagine in theory. The threat of a surveilled society had been a pressing concern for as long as there had been an identity project,” he says, ruing the absence of an open discussion on its pros and cons.

In 2018, the Supreme Court upheld the Aadhaar Act in a majority judgement, but struck or read down some of its provisions—it could be not be made mandatory for opening bank accounts, enrolling in educational institutions, for obtaining mobile SIM cards, or for writing national entrance exams such as NEET and others. Nor was it to be used as proof of age. However, the majority verdict upheld its requirement for IT returns, and that it did not violate the right to privacy. The lone dissenter on the five-judge bench, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, called the entire project unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, the majority verdict’s explicit directions about what Aadhaar should not be used for is violated every single minute in the country. Bhatia writes about Rahul Narayan, a young Supreme Court advocate who was part of a challenge to Aadhaar, and who described himself as “radicalised” by the hearings, particularly after the the government’s “scorched earth tactic” in court with its argument that the citizens have no fundamental right to privacy. This belief has seeped down to the public in fundamental ways.

Those who have witnessed earlier riots know that victims were marked out easily with the help of voters’ lists and local databases held in the depths of bigoted minds.

Many Indians see privacy as a demand that only someone with something to hide, some illegal activity, might make. On the other hand, Aadhaar’s promise to wipe out corruption was attractive to the Indian middle class, its biggest supporters. The lawyer tells Bhatia that more than corruption, it was the bogey of corruption and an “overblown perception” of it that made Aadhaar appealing to Indians.

He worried about something that he confessed he could not articulate in court—that it was a project reminiscent of Nazism. “The Nazis, you know?” he says to Bhatia. “The first thing they do is make a list of everybody. Just imagine how much more precise our riots would be if you know how X is owned by a person who is from a certain religion, and how a particular person is personally related.” Bhatia writes that by the time he checked the notes of that interview in 2023, “the possibility had come to pass. Within two years of our speaking, just a few miles from where we spoke ... men in east Delhi would precisely target Muslim tenants in Hindu homes, and Muslim shops but leave Hindu shops untouched”.

Bhatia provides no evidence when he makes this implicit link between Aadhaar and the 2020 riots. But those who have witnessed earlier riots know that victims were marked out easily with the help of voters’ lists and local databases held in the depths of bigoted minds.

A “reported elegy, an investigative memoir, an attempt to see the roots of Hindutva” is how Bhatia describes his book. His decision to write it was triggered by the hate family members and friends he had loved began spewing in the early years of the last decade. It was all directed at the same target—Muslims. It is an all too familiar story in many Indian Hindu homes today.

Summing up

For sure, the events that these books chronicle were foretold in trends visible even in the pre-Modi years. But the intensity with which they picked up in after Modi came to office cannot be denied. The three books intersect literally too, at many points. For instance, the murders of Dhabolkar, Pansare and Kalburgi are discussed by Ashraf, as he sets the context for the Bhima Koregaon violence, and by Romig—had the Maharashtra and Karnataka police shown a little more interest in hunting down those behind the three murders, Gauri would have been alive. On Bhatia’s tours into the bowels of East Delhi, a Hindu man tells him that all those picked up by the police during the riots were “children” of the “middle class or poor”. Their parents were daily wagers, illiterate and unaware of the law.

It makes one wonder if journalists must now write full-length books to publish their stories and lay out the facts and the context before the public, something that newspapers have stopped doing, with some exceptions.

A victim of the riot that Bhatia interviews said he recognised all of them. “They were not killers,” he said, “not ordinarily, so what made them join a crowd that wanted to kill? Nisar would ask, over and over and over, who was behind them, and why were they not the ones arrested?”

The answer to Nisar is provided by Bhagwan, in Romig’s book. “The pity is,” Bhagwan says about those who killed Gauri and the three others who had been assassinated before her by the same group, “they’re all Shudras, non-Brahmins. They all belong to the lower strata of society. You see how Brahminism has brainwashed them. The ideology is given by the Brahmin, but no Brahmin is caught so far.”

The books raise another question. They are about current events and all three authors are journalists. It makes one wonder if journalists must now write full-length books to publish their stories and lay out the facts and the context before the public, something that newspapers have stopped doing, with some exceptions.

Bhatia does talk about a reporter of the Economic Times who faced so much pushback to his stories on Aadhaar that he stopped doing them altogether, telling his sources to give their leads to some other reporter. On a visit to the Economic Times office, Nilekani was asked what he did in his free time. The reply was telling. “A lot of time,” Nilekani said, pointing to the street outside with its many newspaper offices “goes in environment management.”

Nirupama Subramanian is an independent journalist.