There was a time when historians of India wrapped up their analyses and narratives by 1947. Then there came a time when it became customary to complain about this tendency. Both of these statements hold little water today. Historians now write about early postcolonial India. Informed readers, as a result, are beginning to develop a richer sense of Nehruvian India.

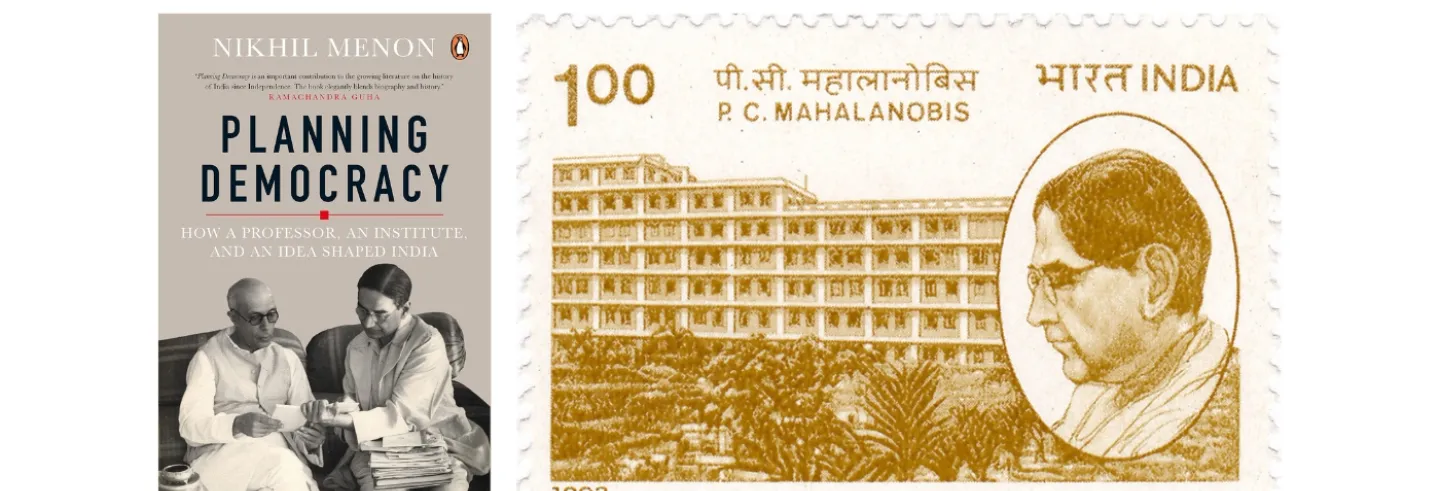

Yet, our knowledge of newly independent India’s experiment with economic planning remains straight-jacketed for the most part. Indian planning today has few admirers. Most believe it was a colossal mistake, while some others think it was at best, a well-intentioned but ultimately wrong policy choice. Nikhil Menon’s Planning Democracy, however, offers a different and far more nuanced picture of Indian planning. It steers clear of questions of 'success' or 'failure' that have overdetermined our understanding of India’s economic planning. Instead, the book takes the idea of “democratic planning” seriously and points out something that is perhaps so obvious that it often misses our attention, which is that “democratic planning” is an oxymoron.

Planning Democracy [steers] clear of questions of “success” or “failure” that have overdetermined our understanding of India’s economic planning.

While economic planning is centralised, top-down, and technocratic; democracy – at least on paper – is about decentralisation and accounting for the popular will. Menon, therefore, asks: how did India reconcile the tensions between economic planning and liberal democracy? And how did this attempt shape the Indian republic’s formative years?

People for planning

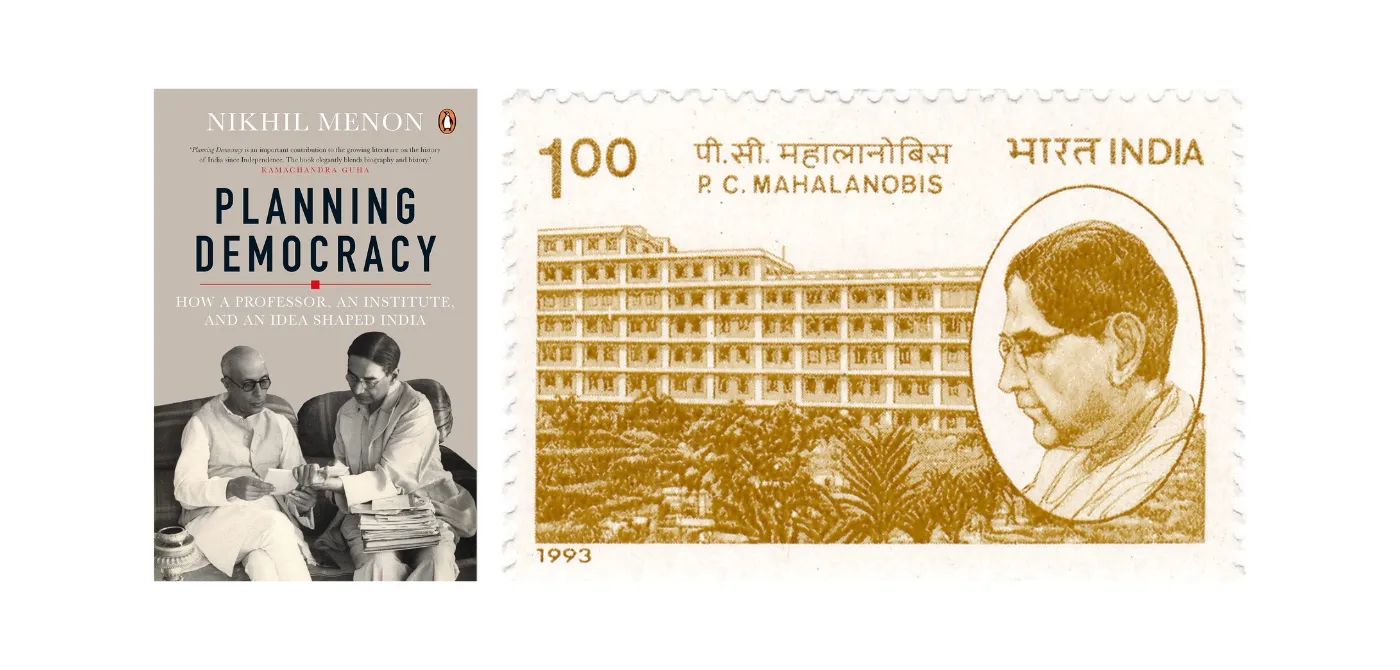

This book is divided into two parts. In the first part, Menon focuses on planning, politicians, and technocrats, particularly P.C. Mahalanobis, a physics professor who became “the ‘presiding genius of statistics in India’” (4). Menon shows how India’s quest for planning meant that statistics came to play a central and, arguably, the most important part in India’s planning endeavour.

Planning logically entailed a union between statistics, sampling, and computing, as well as an attempt by the state to increase its capacity. India would turn to statistics but also go on to become a pioneer amongst Asian countries in conducting sample surveys and in the adaptation of the computer. Indeed, without sampling, the cost and time required to gather relevant data might well have made planning impossible for the nascent Indian state. Without computers, it would have been harder to calculate complex equations and input-output tables requiring hundreds of variables.

India would turn to statistics but also go on to become a pioneer amongst Asian countries in conducting sample surveys and in the adaptation of the computer.

However, neither of these journeys was smooth or even. Overall, while the National Sample Survey Organisation became well-established and globally renowned; India’s quest for computers, Menon shows, got hopelessly tied up with cold war politics. Mahalanobis’ personality aroused American suspicions about his political leanings. As a result, until the early 1960s, India did not have the computing power necessary to process the vast amounts of statistical data it generated.

What was unexpected, Menon points out, was Mahalanobis’ outsized influence over the second Five Year Plan, and through his protege Pitambar Pant, in the third Five Year Plan. What was it about Indian planning and the times in which it was taking its decisive shape that allowed a physicist to sideline professional economists and take over Indian planning?

Mahalanobis here was the right man at the right time. He had become so enchanted with statistics that by the 1930s, he founded the Indian Statistical Institute. He was part of and mingled in the correct social and intellectual milieu globally and came to believe he could shape India’s statistical and economic future. Menon paints a fascinating picture in which Mahalanobis’ energy, enterprise, personality, connections, conviction, and failings; Nehru’s and the Indian government’s faith in the ability of planning to take the country forward; global changes in economic thought; statistical methods and technology; and cold war politics, all came together to make Mahalanobis the most important figure in Indian planning in the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s.

The first section is garnished with some interesting anecdotes that stayed with me even after I finished the book. A digression on Rani Mahalanobis – P.C. Mahalanobis’ wife who directed a study on cottage industries – stands out. The competition between Mahalanobis and Homi Bhabha – who headed India’s atomic programme – for computers is riveting. The story about how sampling came to be accepted in Indian policy circles in 1946 stood out as being especially educative, though it would have been good for the reader if Menon went a little further to analyse the relationship between sampling and the census.

Menon asks why and how India sought to develop a “plan consciousness” amongst its citizens.

The unanswered question for me was, if sampling was indeed so efficient, why did India decide to continue with the census? Were older colonial forms of data collection entirely obsolete for planning? Did the state use any of its inherited infrastructures to make Plan-relevant data collection possible? It may also have been instructive to get a deeper sense of the conflict between the Planning Commission and the finance ministry. But the absence of answers to some of these questions does not diminish the importance of this book in any way.

If the book's first part is instructive, it is the second part that makes the book stand out, and my hunch is that the two chapters in this section might spark further research. Menon asks why and how India sought to develop a “Plan-consciousness” among its citizens. For those wishing to get an overview of this section before getting into the weeds, pages 113 to 117 will be especially relevant. Here, Menon writes:

“The widespread image of the Planning Commissions has been that of aging upper-crust men dressed in starched Khadi or tailored suits, discussing dams and steel plants in dull Lutyens Delhi offices – in short technocratic planning [… but] this blinds us to the ways in which the commission sought to engage the populace. It draws a veil over the political ambitions of planning and masks the extent to which the Indian government reached out to its citizens and the lengths to which the Indian government reached out to citizens to make the plans popular [... Democratic planning] formed the basis of the claim that India was engaged in an experiment that represented a different path in the cold war, one combining democracy and centralized planning in a poor, recently, decolonized country while remaining independent of the two superpowers.”

To learn more about how India and many Indians went about this goal of reaching out to citizens and what were its successes and limitations, one must read this extremely rich section. It is rare for scholars to strike a balance between writing for scholars and writing for an informed readership, but Menon gets it right. This book is a page-turner and, simultaneously, a book where someone might wish to slow down to focus more intently on certain sections.

Conclusion

Planning Democracy is a timely book. We are today in an era where, as Menon points out, the Planning Commission has been shuttered, National Sample Survey reports are being shelved, and the 2021 census has been delayed – perhaps indefinitely. Paradoxically we are now an increasingly data-blind country in an era of big data. Menon’s book is a reminder of what we may lose if we do not, at the very least, try to maintain the integrity of our data and its analysis and how early postcolonial India fought so hard to develop a robust data collection infrastructure.

Paradoxically we are now an increasingly data-blind country in an era of big data.

I end this review with a thought. Menon points out that promoting plan consciousness amongst Indians was not merely a cynical exercise in political aggrandisement, propaganda, and political legitimisation. Nor was this outreach simply a cover for state weakness and the only non-authoritarian way to convince people to give up current consumption and increase savings to make India better tomorrow. Raising plan consciousness was all this and more. It was an attempt to enable “Indians to plot themselves into the saga of development” (121) and paper over the fissures that fracture Indian society. In this context, Menon points out that in 1966, Indira Gandhi, when discussing the fourth Five Year Plan, said India's “people […] were prepared to make all possible contribution[s] for something really big for the state […] this was a human psychology and should not be lost sight of” (122). It is worth considering when India’s political and intellectual mainstream lost sight of this “human psychology.”

It is a sign of our times that while in the 1950s and the 1960s it was thought that planning and quest for industrial modernity and equality could satisfy this “human psychology”, in our times, a radically different post-planning project seems to have taken on the task of satisfying mass psychology.

Gaurav C. Garg is an assistant professor of history at Ashoka University, Sonipat.