There isn’t an exact year when the Asiatic cheetah in India was officially declared extinct. When independent India’s wildlife board met for the first time in November 1952, it worried that the lithe cat might be already extinct, even as it “called for assigning special priority for the protection of the cheetah in central India.”

By then, it had been five years since the last specimens had been shot. Three males, almost certainly brothers were hunted by Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Koriya (now in Chhattisgarh) in December 1947, close to the village of Ramgarh (now in Guru Ghasidas National Park, Chhattisgarh). However, credible sightings of cheetahs in India continued right up until the early 1970s (Divyabhanusinh and Kazmi 2019).

Naming the cheetah

The Asiatic cheetah once roamed in India across a range that spanned – in modern geographical terms – Jharkhand and Odisha to Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, and Gujarat and Rajasthan to central India and into the Deccan. Unlike the popular visual depiction of African cheetahs dashing across vast open grassland plains, the Asiatic cheetah’s habitat, both in India and beyond, was diverse: scrubs, bushlands, arid and semi-arid open lands, and low hills and rocky plateaus interspersed with plains.

By the time the British established political dominance over the subcontinent, though, cheetahs had already become rare. (Kazmi 2019). Extremely small and isolated populations survived in critically low densities across their range. Consequently, we find a perceptible dearth of colonial literature on the cheetahs in India in comparison to the copious notes left behind by British hunters and naturalists on many other mammals and birds of the Indian subcontinent. Then, there was the problem of nomenclature of cheetahs, a problem as old as the history of this spotted cat.

Greek ambassadors at the courts of various rulers in ancient India used the word 'pardalis' to describe all spotted large cats they saw, even as the Greek author Oppian of Apamea (3rd century CE) explained in Cynegetica – his noted treatise on hunting – that the pardalis “are a double race.” One kind of pardalis was “larger to look on and stouter as to their broad backs” [a description of the leopard], the other kind was smaller and very swift “in running and valiant in a straight charge […] that it sped through the air” [evidently a description of the cheetah] (Mair 1928).

Before colonial rule, cheetahs arguably were one of the most culturally important large cats in the subcontinent. They were depicted in art as early as 2,500–2,300 BCE in cave paintings

Ancient Indian texts interchangeably used the Sanskrit words vyaghra, vyala, dvipin, chitraka, chitrakaya, and pundarika for a variety of large wild cats found in the Indian subcontinent, which makes species distinction tricky. Other languages had separate names for the cheetah and the leopard, but these tongues were never the patronised by courts or considered for producing classical texts. Writers from the Sultanate period resolved the problem of distinction with the use of distinct Persian names for the two animals: yuz (or sometimes yuz palang) for the cheetah and palang for the leopard. However, it was the Mughals who popularised these distinct names so that yuz became commonplace for the cheetah.

British naturalists and zoologists – including some of the most influential names of the era such as Edward Blyth, W.T. Blanford, T.C. Jerdon, and R.A. Sterndale – renewed the confusion. They suggested the cheetah, as the “true pard,” should be referred to as ‘leopard’ (some preferred calling them ‘hunting leopards’). This led the generalist authors of colonial gazetteers and government reports mixing up cheetahs and leopards while detailing the animals destroyed every year across various provinces (Divyabhanusinh and Kazmi 2019). It even caused British scholars working on Mughal texts to translate yuz as 'leopard'.

'Coursing'

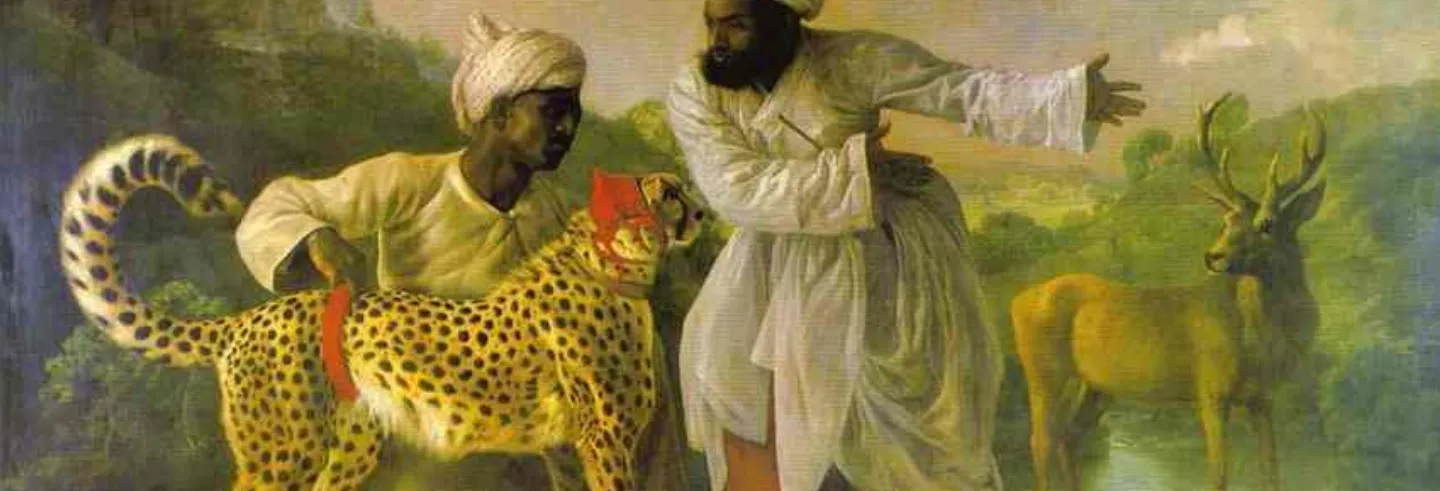

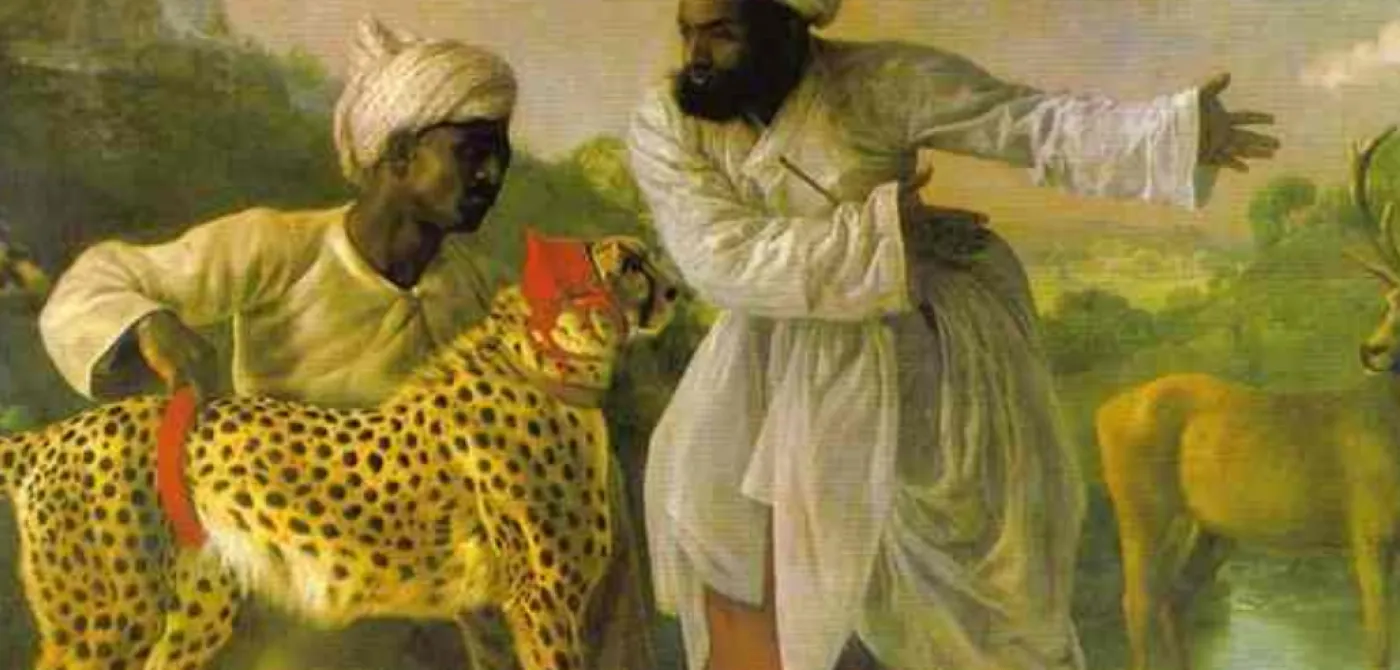

Before colonial rule, cheetahs arguably were one of the most culturally important large cats in the subcontinent. They were depicted in art as early as 2,500–2,300 BCE, in cave paintings at Kharvai and Khairabad and in the upper Chambal valley, in Madhya Pradesh. (The English word ‘cheetah’ itself is derived from the Sanskrit chitraka, ‘spotted’ (Divyabhanusinh 2006).) During the rule of the Great Mughals, the cheetah was lavishly depicted in paintings and illustrated manuscripts, including in the Anwar-i Suhaili, a Persian version of the Sanskrit Panchantantra.

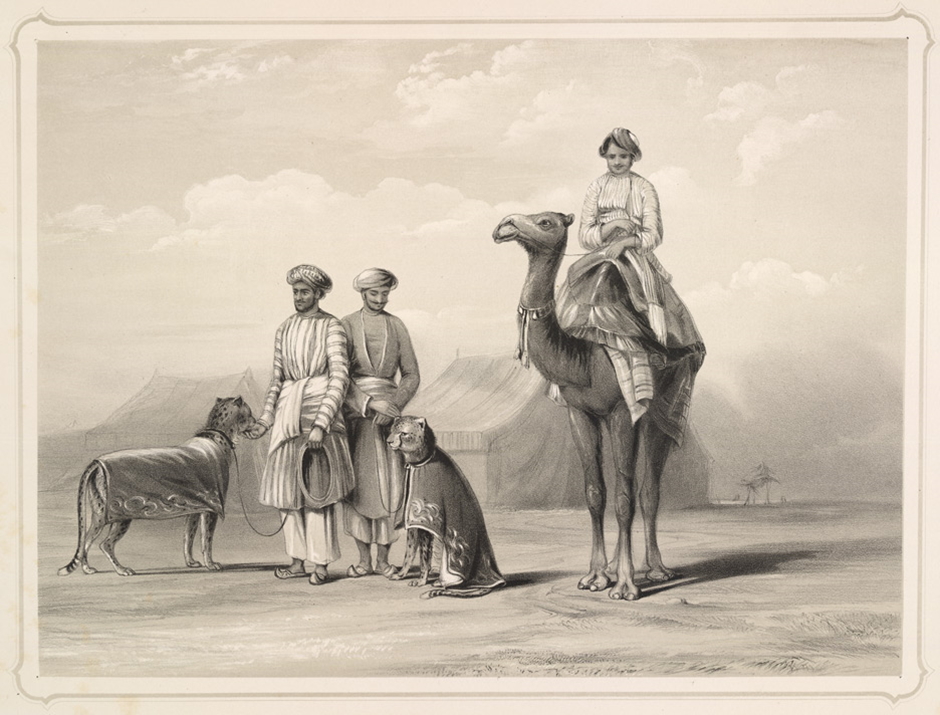

One of the main reasons behind the increasing cultural importance of cheetahs during the mediaeval era was the popularisation of the peculiar ‘sport’ of ‘coursing with cheetahs’, wherein the lissom cat was trained to hunt down prey, almost always blackbucks. It was this ‘sport’ that made the cheetah famous which would cause their precipitous decline.

Breeding cheetahs in captivity was almost impossible (Jahangir recorded a rare occurrence in 1613; the next known success afterwards was in 1956 in the Philadelphia Zoo.) Trapping them in the wild to ‘break’ them in captivity was the only way to meet the demand from the ever-rising popularity of the sport throughout the medieval age and into the colonial era of zamindaris and princely states. By the early 18th century, the constant removal of cheetahs from the wild, especially females and cubs, had made the population reach a tipping point, even though even though their prey base and habitat survived till much later.

The earliest record of coursing with cheetahs comes from the Manasollasa or Abhilashitarthacintamani (1129-30), a treatise credited to the Western Chalukya ruler Someshvara III (though probably actually composed by his court poets). Among many other subjects, the Manasollasa discusses hunting antelope (mrgaya) with trained cheetahs. The elaborate detail points to a “well-developed sport” and the historian Divyabanusinh (2006) suggests that “cheetahs could well have been trained for hunting much earlier.”

Akbar was especially fond of cheetahs, as attested to by his son Jahangir, who wrote in 1613 that his “revered father once collected together 1,000 cheetahs.” The zest for the sport was passed down to successive rulers.

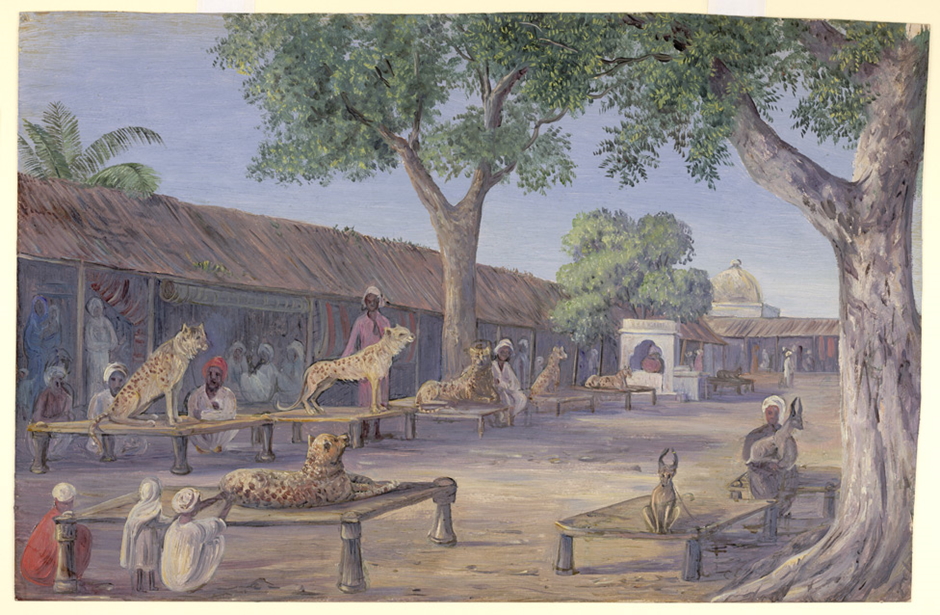

The sport really took off in the subcontinent during Mughal rule. Akbar was especially fond of cheetahs, as attested to by his son Jahangir, who wrote in 1613 that his “revered father once collected together 1,000 cheetahs.” The zest for the sport was passed down to successive rulers. The Mughal empire maintained an elaborate setup of cheetah trappers and trainers. The Mirat-i-Ahmadi by Ali Muhammad Khan, a treatise on the administration during the reign of Aurangzeb (1658-1707), detailed cheetah-trapping locales within Gujarat, where “there are [normally] twenty-two [cheetah] catchers [at a time, presumably on a permanent basis] with a monthly salary of Rs. 80” (Ali 1930, Divyabhanusinh 2006). The French traveller Jean de Thevenot, who was in India during the early years of Aurganzeb’s reign, recorded the procurement of cheetahs in Gujarat for the imperial menagerie. “The Governor suffers none to buy them but himself.”

Trapping manuals

Some of the earliest records of the techniques to trap wild cheetahs also come from the Mughal period. According to Abul Fazl, author of the Abkarnama, prior to Akbar’s era, cheetahs were caught in odis, camouflaged pit-traps dug deep along paths frequented by cheetahs. (This method of could have been borrowed from Afghanistan, where a similar technique was described in a text by a cousin of Babur, Sultan Husayn Bayqara Mirza of Herat.) To avoid cheetahs getting injured or at other times escaping the pits, Akbar modified the pit-design to make them shallower and installed with an automatic trap door to prevent escape. This method persisted into the 19th century, when James Forbes (1813) received a gift of two cheetahs from “a Chief” in Gujarat, “brought to me soon after they were caught; which was effected by digging deep pits, and covering over with boughs near the places they frequented; which are easily discovered by certain trees, against which they are fond of rubbing themselves."

The Akbarnama also describes other methods of capture, such as the use of a specially prepared stockade and by lassoing wild cheetahs after a chase to tire them out. (The latter technique was also used in Africa by white men to trap cheetahs (Delmont 1931) that were then exported across the globe, including to Indian princely states from 1918 onwards.)

Colonial-era sources described other techniques. The Saidnamah-i Nigarin of Kanwar Balwant Singh Panwar, the risaldar (master of the stable) of the princely state of Ajaigarh (now in Panna district of Madhya Pradesh), tells us about trap-cages, much like the ones used today by forest departments to catch errant tigers and leopards in India. The Chityasambandhi Samanya Mahiti, the cheetah training manual of Baroda state, gave an account of trapping mothers with cubs by tracking them to low hilltops (which, incidentally, is very similar to the habitat of the last extant Asiatic cheetahs in Iran). There they would be surrounded by herds of cows and funnelled towards at opening, where the cheetahs would then be ensnared (Divyabhanusinh 2006).

Few British naturalists or hunters witnessed and recorded first-hand how a cheetah was trapped. Most of their writing on this subject were notes taken from "native trappers”

British hunters thought the sport of coursing with cheetahs was “unsportsmanlike,” preferring to hunting by rifle or spear. Consequently, few British naturalists or hunters witnessed and recorded first-hand how a cheetah was trapped. Most of their writing on this subject were notes taken from "native trappers” (Divyabhanusinh and Kazmi 2022).

Major H. Shakspear, a keen hunter who altogether killed 11 cheetahs in the wild, in 1867 detailed a technique from the Deccan, practiced by the Pardhis, An Adivasi community of central India and Deccan who have historically been hunters and trappers. The “cheetawala Pardhis” – a clan within the larger Pardhi community – trapped cheetahs and sold them to princely states and zamindaris (Divyabhanusinh 2006). They “catch leopards [Shakspear explained why he preferred this term for cheetahs] by applying a kind of very strong bird-lime to the branches of the trees they inhabit. The animal becomes quite helpless and unable to show fight; the Pardees throw a large coarse blanket over him when clogged with the bird-lime, and thus easily secure him (Shakspear 1867: 190)

By and large common to all accounts of trapping was snaring cheetahs around a 'favoured tree'. The Saidnamah as well as the Chityasambandhi Samanya Mahiti asserted that once the cheetahs became sexually active, they would visit certain trees repeatedly and ‘play’ around them. (For that reason, the Chityasambandhi Samanya Mahiti recommended the beginning of winter as ideal for trapping, for it claimed that cheetahs became sexually active in that period. The Saidnamah recommended the “months of Kawar [and] Kartik of winter and the beginning and middle months of summer” (Divyabhanusinh 2006).

Once such ‘playing grounds’ (akhur) were identified, trappers laid a phanda, a snare-trap made of deer gut, around the cheetah’s favoured trees and waited in hiding – sometimes for days on an end – till the cheetah appeared. British zooligists such as R.A. Sterndale and W.T. Blanford, while recording similar descriptions of capture of cheetahs, also made note of the favoured trees. “On this tree it sharpens its claws, leaving marks that are recognized by the hunters," explained Blanford (1888). Shakspear on the other hand noted that “the native shikarrees aver that they [cheetahs] bring forth their young in the hollows of trees.” Based on notes taken taken from cheetah trappers of Hyderabad state, the British surgeon George Ure asserted that cheetahs go “to a tree situate about three miles from his den, where, after scraping a hole in the ground, he relieves himself and then covers his excrement.” The proclivity of cheetahs hanging around their favoured trees also led to them being killed by British hunters. A Colonel E.A. Hardy described how he tracked six cheetahs to one of their favoured trees, where he speared three of them (Hardy 1878).

[The cheetahs] "were entangled by all four feet before they knew where they were. The Vardis made a rush […] A country blanket was thrown over the heads of the animal, and the two fore or hind legs tied together. The carts had come up by this time; a leather hood was substituted for the blanket."

The Saidnamah provides a detailed account of the technique of capturing the cheetah once one was ensnared around such marked trees. As soon as one was ensnared, the Saidnamah asserts, the trappers would come out of hiding and approach the entangled cat with a branch of a tree with leaves on it. The desperate cat would angrily bite the branch and in the process get its eyes covered in leaves. At that moment a hood (topi) was thrown over its eyes and a cot placed over the animal to restrain it. The cheetah’s front and hind feet were tied up. The Chityasambandhi Samanya Mahiti of Baroda, also reiterates the same method, with minor modifications. (Divyabhanusinh 2006).

A rare first-hand observation of cheetah trapping by a British officer – perhaps the only one extant – provides us an eyewitness account of the techniques described in these manuals. Writing under the pseudonym of “Deccannee Bear” in the sporting newspaper The Asian, the officer described accompanying some Pardhis to a cheetah trapping exercise in 1880:

“The nooses were of the same kind as those used for snaring antelope, made from the dried sinews of the antelope. These were pegged down in all directions, and at all angles, to a distance of 25 to 30 feet from the tree […] An ambush was made of bushes and branches some fifty or sixty yards away, and here, when the time came, I and three Vardis [sic, Pardhis] ensconced ourselves… At last the sun commenced to sink, and the men who were looking round in all directions, suddenly pointed in the direction of the north. Sure enough there were four cheetahs […] and all raced away as hard as they could in the direction of the tree […] and were entangled by all four feet before they knew where they were. The Vardis made a rush […] A country blanket was thrown over the heads of the animal, and the two fore or hind legs tied together. The carts had come up by this time; a leather hood was substituted for the blanket – a rather ticklish operation, during which one man was badly bitten in the hand. The cheetahs know how to use their teeth and claws […] The next morning, I went to see the cheetahs and found that they had been tied spread-eagle fashion on the carts, and with their hoods firmly tied. (Sterndale 1884)

Taming the cheetah

In the wild, cheetahs were often ambush predators rather than exclusively being predators of chase. Ure’s notes described the cheetah’s ecology and hunting styles in the wild:

“Hunting Leopards are numerous near Hydrabad [sic], and live in holes among the rocks on the hills, or rocks that are near to the plains which the Antelopes frequent. This animal feeds only once every third day; and after devouring his prey he retires to his hole […] he goes to the nearest hill or rising ground, where he looks out for the Antelopes; and if the ground is not very favourable for his approaching them without being seen, he makes, a circuit to the place where he thinks they will pass near; and if there is not enough to cover him, he scrapes up the earth all round, and lies flat, until they approach so near that by a few bounds he can seize on his prey” (Blyth 1857).

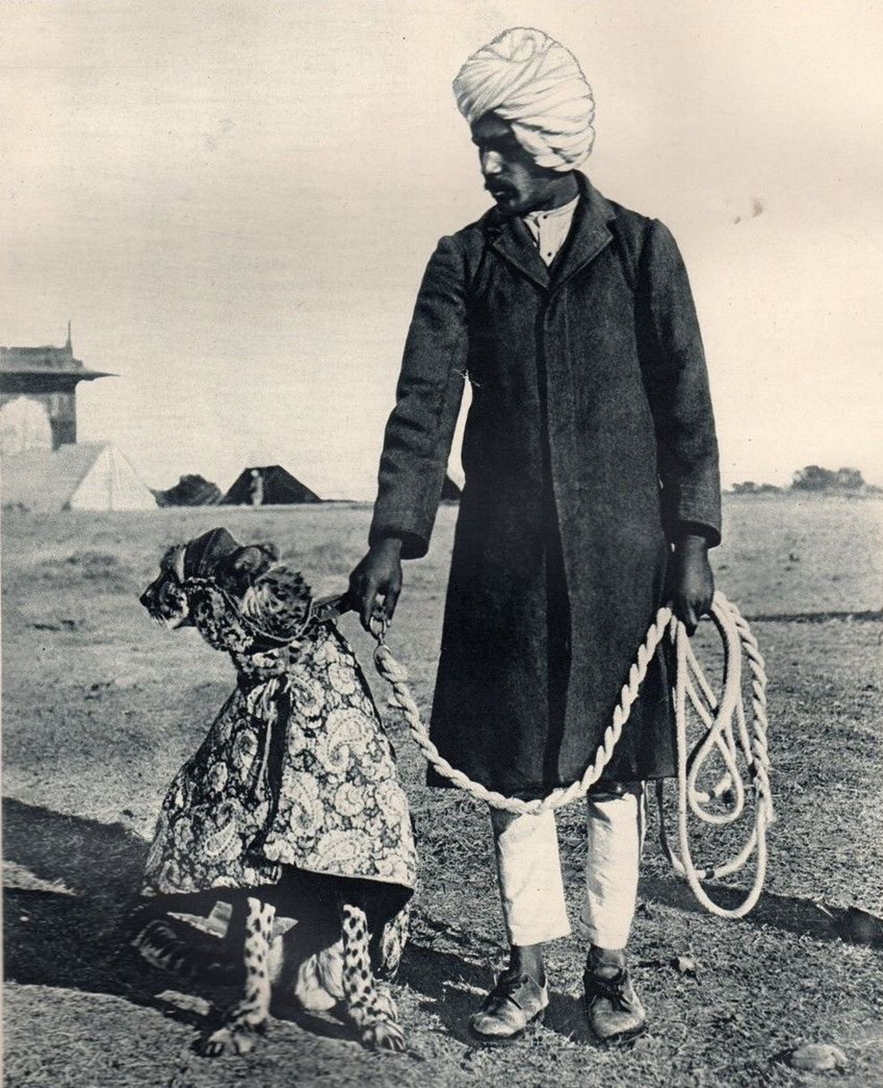

This meant that once the cheetah had been trapped, it had to be trained to course. Both the Baroda and Ajaigarh Manuals, and medieval era texts such as Baznama, give extensive details on various methods to tame the cheetahs and prepare them for the sport. The Saidnamah recommended uttering terms of endearment to get the cheetah to eventually grow fond of his keeper. (These included ‘Aa-ha-ha-ha-ha-Aai’ during feeding; ‘aao beta, waah beta’, come on son, well done son; ‘chale chalo bahadur’, march on, brave one.) It also suggested taking the cheetah to the bazaar to get it used to crowds, a process called pherna pheri par (Divyabhanusinh 2006).

Witnesses observed some of these techniques. After capturing the cheetahs, 'Deccannee Bear' wrote that, “Women and children are told off to sit all day long close to the animals, and keep up a conversation, so that they should get accustomed to the human voice [ …] I was told they would be ready to be unhooded and worked in about six months’ time.” Thevinot, the traveller in 17th century India, too mentioned that “they whose care it is to tame them, keep them by them in the Meidan [open ground], where from time to time they stroke and make much of them, that they may accustom them to the sight of the man”. (Sen 1949; Divyabhanusinh, 2006).

But it was not all affection. J.G. Wood noted that after capture the cheetah was “tied in all directions, principally from a thick grummet of rope round his loins”, with a hood on his head covering his eyes.

“The keepers and their wives and families reduce him to submission by starving and keeping him awake. His head is made to face the village street, and for an hour at a time several times a day his keepers make pretended rushes at him and wave clothes, staves, and other articles in his face. He is talked to continually, and women’s tongues are believed to be the most effective anti-soporifics. [… Due to] the effects of hunger, want of sleep, and feminine scolding, and the poor cheetah becomes piteously, abjectly tame. (Kipling 1892).

The end of an era

By the dawn of the 20th century, trapping was increasingly difficult, given the rarity of the cheetah. Yet, the lure of coursing with cheetahs was still as strong as ever amongst the many princes of India. Consequently, they turned towards Africa for supply of cheetahs.

As early as 1914, Bhavnagar sent an officer to Africa to import cheetahs; though the outbreak of the World War I put paid to that effort. As soon as the war ended, in 1918, cheetahs from Africa started arriving in India. (Before that, the only known record of any African cheetah having come to India was a specimen that arrived in Calcutta in 1890-91 to be housed in the Alipore zoo.) Baroda, Bhavnagar, and Kolhapur directly imported African cheetahs which were then subsequently sent from these three importing states to other princely states (Divyabhanusinh 2006).

By the late 1920s, almost all cheetahs in captivity in India were of African origin. The Asiatic species that occurred in the Indian wilds neared extinction. The traditional cheetah trappers moved on to trapping other animals or changed professions. With this, the sun finally set on the centuries-old Indian tradition of cheetah-trapping, and soon would do so for the Asiatic cheetah in India itself. The last of them found refuge in niche habitats around the edges of sal forests of east-central India — until one day, their tracks faded away forever from the country (Kazmi 2019).

Raza Kazmi is a conservationist and wildlife historian. He is writing a book tentatively titled The First of the Nine: The Story of Palamau Tiger Reserve.