The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) often appears in the news, though not always for its significant contributions to the discovery and conservation of India’s built and excavated heritage over the past 150 years. Recently, an ASI archaeologist’s excavation report of his work at the site of Keeladi near Madurai in Tamil Nadu has become the bone of contention between the Union Ministry of Culture, which administers the ASI, and the State Government of Tamil Nadu.

The disagreement is over the archaeologist’s claim that the remains at Keeladi date to around the 5th century BC. This would place the Tamil civilisation earlier than the Indus Valley Civilisation and suggests that Tamil culture may have existed before any other known civilisation in India. The ASI reportedly requested the archaeologist to amend the date, but he refused, citing scientific evidence in support of his claim. The ministry and the ASI have resorted to transferring the archaeologist to what is seen as an insignificant post.

Tamil scholars and politicians have criticised this move. According to The Hindu of 19 June 2025, the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu has vowed that it will not let Parliament function unless the Keeladi excavation report is immediately released without changing the date given by the archaeologist.

This controversy highlights ongoing issues with the management and status of the ASI. Established in 1861, the ASI is, as its name suggests, a scientific research organisation specialising in archaeological excavation. Questions about archaeological accuracy, dating of excavated sites, and historical perspectives backed by academic scholarship and technical evidence should be left to be decided by those in the ASI who are qualified to rule on them.

Scholarship, academic findings, and the legal position were ignored for the political advantage of keeping a religious and emotional issue open to all manner of interpretation.

Unfortunately, the ASI lacks autonomy, a commitment to upholding scholarship, a professional management cadre, and the power to generate its own financial resources. It is totally under the control of the union government. Such is the lack of credibility of political dispensations of any hue today that nobody has any reason to believe that the union or the state governments are promoting the ASI for any genuine academic, historical, archaeological, or anthropological reason.

Such a situation is certainly not new to the ASI. More than a decade ago, the Ram Setu issue saw the ASI’s original stand based on the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act, 1958 overturned by an ultra-cautious union government with an eye on political gain. Scholarship, academic findings, and the legal position were ignored for the political advantage of keeping a religious and emotional issue open to all manner of interpretation. Judicial proceedings have been initiated regarding the status of Ram Setu, and the matter still remains unresolved.

Another instance where scholars questioned the ASI’s credibility and independence as an expert body concerned its 2003 excavation report at the site of the Babri Masjid demolition and the area beneath it. The ASI’s findings were referred to in the Supreme Court verdict of 2019, which ultimately led to the construction of the Ram Mandir at the site.

The point being made here is that the ASI’s standing as an academic and scientific expert body on archaeological subjects is continually compromised because of its inability to take a stand based on its own knowledge and expertise. Further, its meagre resources are often frittered away on frivolous projects proposed by the political and the non-political executive, which does not appear to betray any understanding or appreciation of the legacy of the institution.

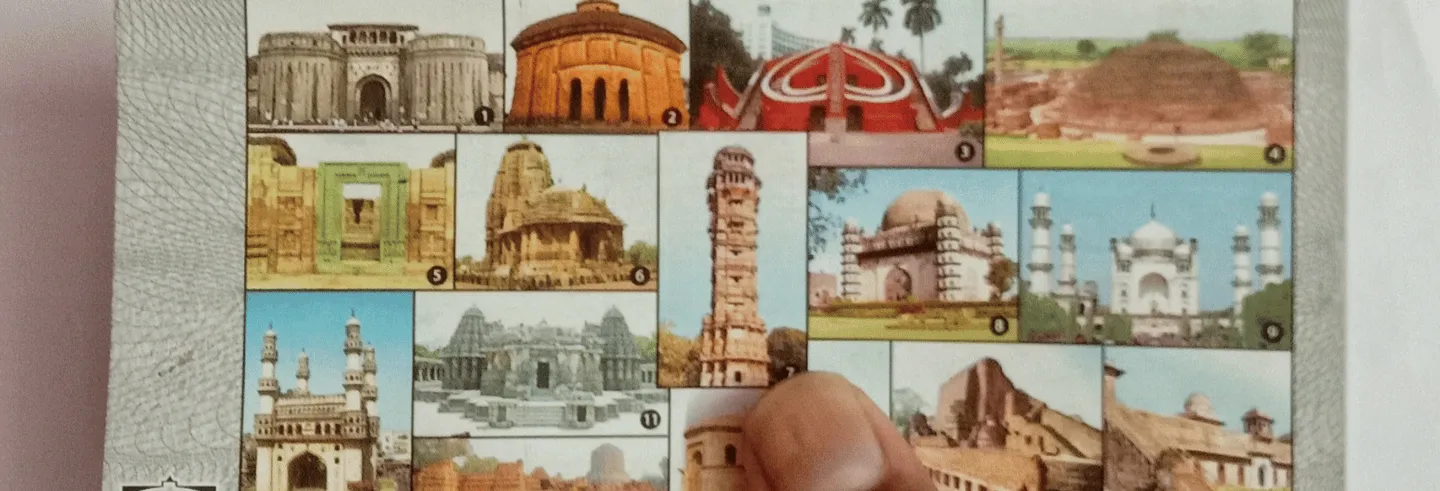

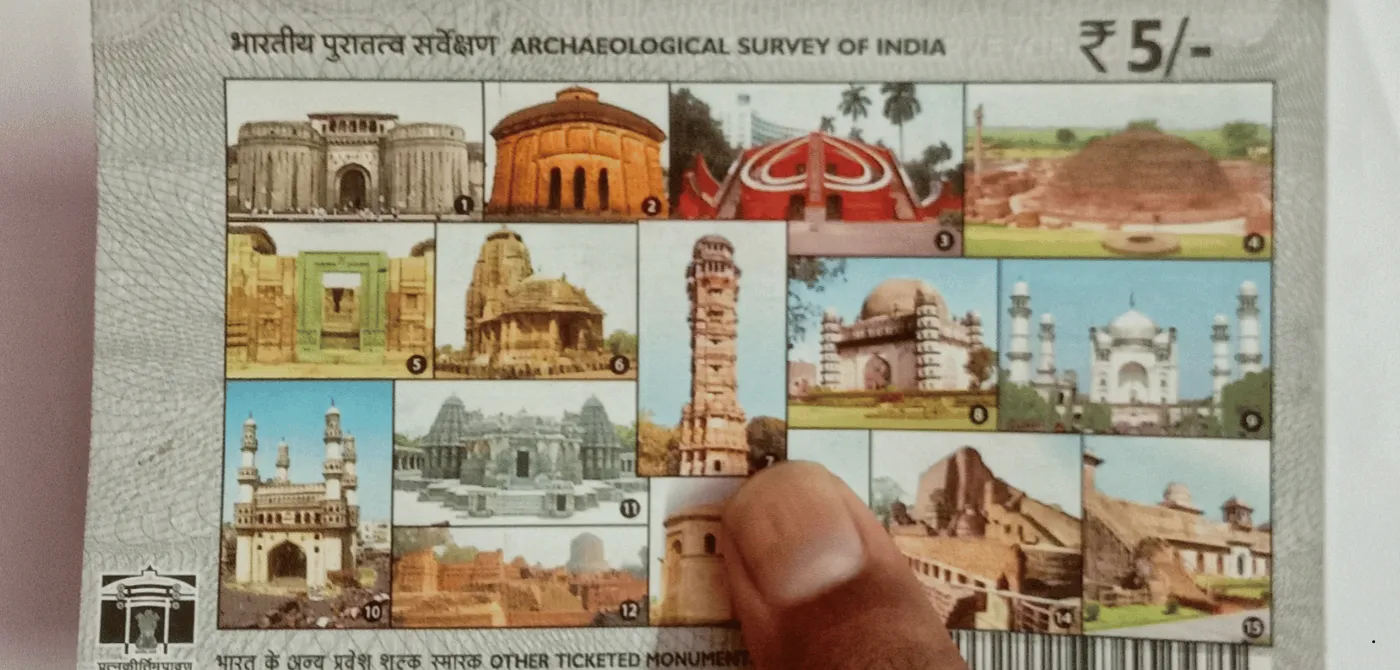

The ASI badly needs professional management. First, it needs autonomy and decentralisation to pursue its mandate. At the last count, the ASI had the responsibility of looking after more than 3,500 monuments of national importance all over the country, besides its work of excavation. This excludes monuments and sites under state governments. The area of a site could range from a single kos minar (milestone) to over 60 square kilometres, as in the case of Hampi. A further layer of complexity is added by that the ASI does not own all the sites it is responsible for. Since heritage sites are located in various regions, it is important to coordinate with state governments and to be sensitive to the local and regional communities’ feelings about their heritage.

The mandate of the ASI could be undertaken with some integrity only if its functioning and its policy decisions are not subject to political vagaries.

This kind of complexity could be best addressed by not consolidating all decision-making in the national capital and decentralising it among different circles and regions. Besides, the mandate of the ASI could be undertaken with some integrity only if its functioning and its policy decisions are not subject to political vagaries. An autonomous society with subsidiaries or sister societies across India, with their own management, by-laws, and with only a very nominal administrative affiliation to the union or state governments would be the desirable solution.

Second, the ASI needs the autonomy to generate its own resources. Currently the practice is for the money raised from ticketed monuments to be assimilated into government revenues. The ASI is allocated funds for its functioning from the union budget. This could be replaced by the ASI having the autonomy to plough back its ticket revenues into the upkeep of the monuments that generate it.

Which monuments should be ticketed and which should not could be decided by an autonomous ASI through expert committees, with market surveys, legal knowledge, and financial viability considerations. Countries such as Singapore and China could provide models for this. This could be one of the many options that the ASI and indeed the government would need to explore to augment the organisation’s resources. Funding of heritage continues to be a difficult issue almost universally.

Third, the ASI employs an array of scholars in archaeology, history, epigraphy, materials sciences, engineering, horticulture, and architecture. It has undoubted technical expertise in calligraphy, photography, and conservation. These professional scholars and experts need effective personnel management to support their career growth, keep them motivated, and provide opportunities for continuous learning. This will enhance their contributions to the ASI.

The ASI also needs affiliation to professional universities for research and training of its personnel. This would require a detailing of how career management with maximum upward and horizontal mobility could be achieved, given the structure and format of the organisation.

Fourth, monuments and sites require the presence of sensitised security personnel in adequate numbers. Here, the union government could consider forming a Central Monument Protection Force (CMPF) on the lines of the Central Industrial Security Force (CISF). The wealth of our built heritage and the priceless artefacts in our museums should not be entrusted solely to private security agencies on short-term contracts. Models of countries such as France could be studied for adaptation. Apart from security, the sites and monuments need the presence of trained personnel to assist visitors and ensure they have a safe sightseeing experience.

Tourism has to encourage maximum footfalls and the ASI has to conserve and protect, which might often imply saving sites from the burden of footfalls.

The new force could recruit retired police and military personnel, as well as other qualified individuals from local communities, ensuring both experience and local knowledge. It should operate entirely under the authority of the union government. Clear terms and conditions must be established, outlining its responsibilities, accountability, and its formal working relationship with the ASI.

Fifth, the ASI has an intricate relationship with tourism in India. For the most part today, it is seen that tourism rides piggy-back on ASI monuments and sites. Think of the Taj Mahal, the caves of Ajanta and Ellora, or the ruins of Hampi, and this immediately becomes obvious. But the mandates of tourism and the ASI are antithetical.

Tourism has to encourage maximum footfalls and the ASI has to conserve and protect, which might often imply saving sites from the burden of footfalls. It is important for the ASI and tourism authorities to develop protocols that protect heritage sites from damage caused by excessive visitors, while also ensuring a positive and convenient experience for them. For the latter, the ASI would need to ensure security and safety of its premises.

Further, there would be the need of a commercial wing within the ASI to liaise with tourism and to handle ticket sales, souvenir shops, paid toilets and other infrastructure facilities, and permissions for professional photography and filming. These would constitute more sources of revenue for the ASI.

Sixth, India’s archaeological and architectural legacy is divided for purposes of custody and maintenance among the union, states, local governments, and private trusts and foundations. The present procedure for declaring monuments of national importance could be continued. Other monuments and sites—including those not yet officially claimed—should be managed jointly by state and local governments. These authorities would be responsible for providing security and addressing any legal or procedural matters related to heritage protection or the safeguarding of citizens’ rights. This would involve a re-imagining and re-assigning of roles to states and local governments and a new set of protocols for smooth transactions between them and the ASI.

Seventh, the ASI has made its contribution to the conservation of world heritage in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. An autonomous ASI, focused on subject expertise, would be better positioned to strengthen and expand its role in international heritage preservation. To achieve a greater and more meaningful international presence, the ASI should build networks with universities and research institutions abroad, while also providing similar opportunities within India.

Universities could consider offering professional courses in the economics of heritage management, a complex field that is still evolving as a field of study.

Eighth, the heritage of India offers unlimited scope for research, scholarship, skilled jobs, professional careers, public-private partnerships, and for citizens’ action and voluntary groups. Universities could consider offering professional courses in the economics of heritage management, a complex field that is still evolving as a field of study. India has the potential to become a leader in this because of the diversity and historical variety of its archaeological heritage. Students would have a wide range of specialisations to choose from within heritage studies, opening up numerous opportunities in the field.

India’s archaeological heritage is remarkable, both in its scale and its diversity across different eras and dynasties. The ASI stands out as an institution, distinguished by the breadth of its mandate and the depth of its expertise, both nationally and internationally. Its role in uncovering and preserving India’s past is truly significant.

The ASI cannot be reduced to the level of a government office that treats the handling of heritage as yet another perfunctory duty. We owe it to this institution to re-imagine it professionally for its continued growth and enriched development. We cannot afford to let the ASI down. It deserves to be nurtured so that it continues to benefit future generations in India and around the world.

The views expressed here are personal.

Juthika Patankar is a visiting faculty member at the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics and a member of the Pune International Centre. A former IAS officer, she served as Additional Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) between 2011 and 2013.