The “rare” in rare diseases can be quite a misleading term. Though individually rare, these disorders affect nearly 5% of the world’s population, causing severe physical and mental deformities in 300 million to 400 million people. Most of them have genetic causes associated with mutations or alterations in specific genes, and are thus collectively termed as rare genetic disorders or RGDs.

…[T]he commercial market has so far been unable to offer significant returns on investment for pharmaceutical companies to focus on rare genetic disorder drug development.

About 8,000 such disorders have been identified worldwide, posing a significant global challenge. India is no exception, with approximately 450 reported disorders and more than 90 million affected individuals, though reliable epidemiological data on prevalence and disease numbers is scanty.

The clinical profiles of rare genetic disorder patients include varying and often life-limiting symptoms. Mostly affecting children, they carry a huge socio-economic, emotional and physical burden on affected families. Manifesting at birth or from an early age, rare genetic disorders disproportionately impact infants, with one third of affected children failing to reach their fifth birthday.

With an average lag of five to seven years to reach an accurate rare genetic disorder diagnosis, patients and their families face an array of doctors and specialists before they can identify their often-incurable affliction. A vast majority of rare genetic disorders lack targeted treatments, compounding the urgency of research efforts for developing affordable diagnostics and therapeutics.

Rare genetic disorders have been classified as a specific category for nearly half a century, with the US Orphan Drug Act of 1984 specifically encouraging research and development (R&D) for treatment and therapies. In India, rare genetic disorder treatments fall in the “orphan drug” category as well, defined as a therapeutic that targets less than 5 lakh individuals (New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules, 2019).

However, the commercial market has so far been unable to offer significant returns on investment for pharmaceutical companies to focus on rare genetic disorder drug development. Developing effective drugs remains a challenge due to relatively low numbers of patients for a particular disease and its varied clinical manifestations depending on the specific mutations involved. Even among individuals diagnosed with the same disorder there is a wide range of conditions that differ significantly in symptoms and outcomes, making generic drugs less likely to be effective. The cost for R&D is therefore significantly high as is the manufacturing due to the small scale.

Of the more than 400 US Food and Drug Administration- (FDA) approved orphan drugs on the market, only about 10–12 are available to Indian patients, even though most of their active pharmaceutical ingredients are manufactured locally. Import costs make most drugs unaffordable, yet pharmaceutical companies remain reluctant to venture into domestic development without clear legislation and incentives. While a few industries offer orphan drugs to Indian patients under charitable access initiatives, the current state of rare genetic disorder therapeutics leaves much to be desired.

Cell and Gene Therapies

Less than 5% of rare genetic disorders are currently treatable and many require lifelong management in medical settings. Standard care for many rare genetic disorders centres on supportive treatments such as enzyme replacement for selected metabolic disorders and hematopoietic stem-cell transplants for some blood disorders, each with accessibility and affordability constraints. The absence of definitive, personalised treatments intensifies the physical and emotional burden on patients and their families, severely impacting quality of life.

With the rise of technologies such as CRISPR-based gene editing, the gap in rare genetic disorder therapeutics is being filled by cell and gene therapies that offer the chance of an actual cure as opposed to disease management procedures.

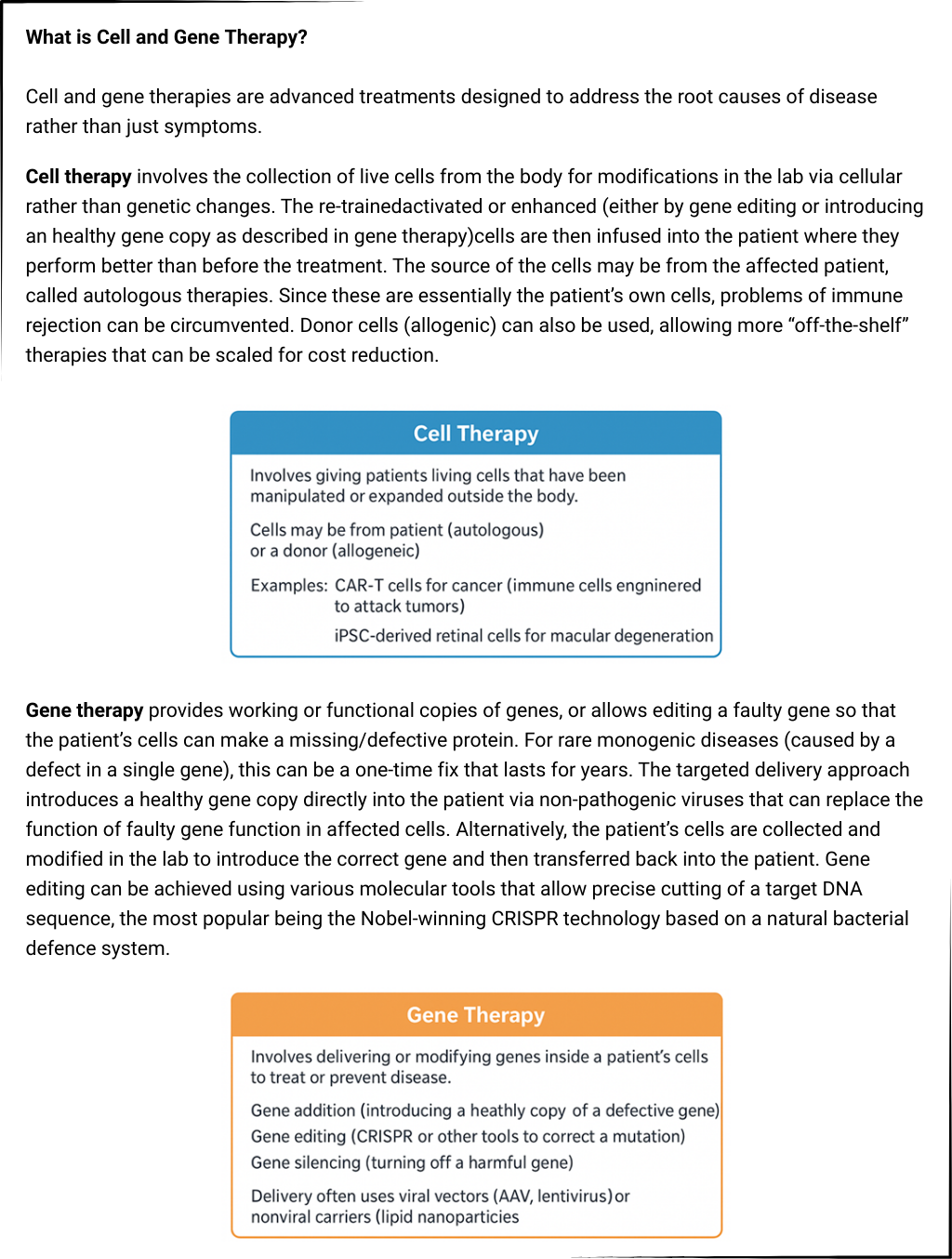

What if there was a way to shift the focus from symptom management and repetitive therapies to curing these patients so that they no longer had the disease? Cell and gene therapy (CGT; see Box 1) offers just such a paradigm shift using state-of-the-art tools of molecular biology to address the root cause of diseases.

In recent years, with the rise of technologies such as CRISPR-based gene editing, the gap in rare genetic disorder therapeutics is being filled by cell and gene therapies that offer the chance of an actual cure as opposed to disease management procedures. With the historic breakthrough achieved with baby KJ in the US in February 2025, CRISPR gene editing is poised to become the face of personalised treatment and the team at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has obtained approval to begin studies for scaling gene therapy.

Cell and gene therapies are especially transformative for single gene disorders, where replacing or repairing the faulty gene can dramatically improve or even cure the condition. A medical breakthrough for in vivo (inside the living body) gene therapy was achieved in 2017 with Luxturna, the first FDA-approved prescription gene therapy product to help improve functional vision in patients with an inherited retinal dystrophy. A single sub-retinal injection delivering a healthy copy of the defective RPE65 gene into the patient’s retina (thus producing the missing enzyme) restored the patient’s ability to respond to light.

This set the stage for cell and gene therapies for rare genetic disorders, with Zolgensma (delivering functional SMN1 for spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA) approved in 2019. The current price of Rs. 16 crore, however, makes Zolgensma unaffordable for most SMA patients in low- and middle-income countries. As a result, treatment access programmes and, more recently, crowdsourcing efforts have become the only viable options for importing and administering the therapy to Indian recipients.

Similar approaches are being developed for blood disorders. For haemoglobin-related disorders, cell and gene therapies rely on either delivering a functional adult haemoglobin gene to the patient or activating their fetal haemoglobin by gene editing. FDA approvals for sickle cell disease (Lyfgenia) and β-thalassemia (Casgevy) mark the entry of ex vivo (out of the body) gene editing into mainstream clinical care.

In other scenarios, gene therapy aims to correct enzyme deficiencies at the source by introducing a functional gene into hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), capitalising on the ability of gene-modified blood cells to act as long-term enzyme factories. This is particularly useful in metabolic and lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs), where a faulty gene leads to a missing or defective enzyme that causes large molecules to accumulate inside cells, leading to cell damage and death. A few biopharmaceutical companies are currently developing viral vectors for common lysosomal storage diseases such as Gaucher, Fabry, Pompe, and mucopolysaccharidoses.

Other cell and gene therapies targets include eye, central nervous system, and skeletal muscle disorders, where localised delivery or tissue-specific viral vectors target hard-to-reach cell types. The FDA’s accelerated approval for gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) reflects the success of the cell and gene therapy approach in slowing the progression of neuromuscular degeneration. Though not a complete cure, the introduction of functional, albeit shortened, dystrophin helps compensate for the loss of the normal dystrophin in DMD patients, restoring muscle function and strength to some extent.

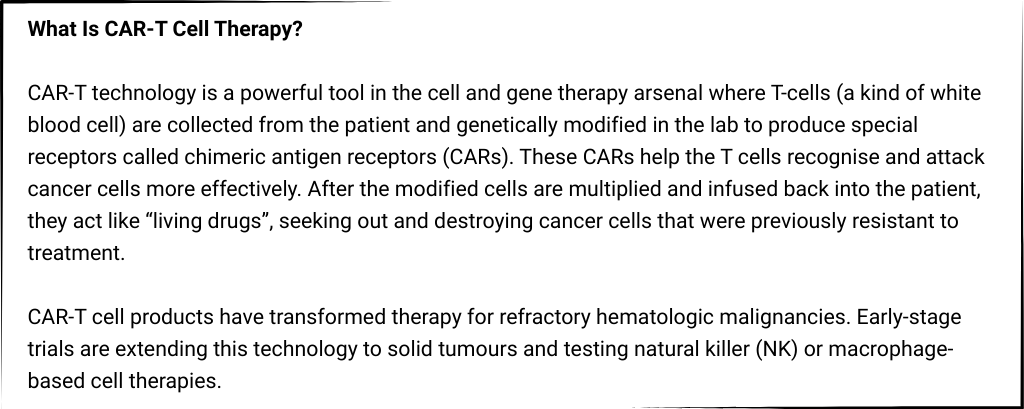

Beyond monogenic disorders, cell and gene therapies are reshaping cancer treatment as well. For example, CAR-T cell therapy is a type of personalised cancer treatment that uses the patient’s own immune cells to fight and kill the body’s cancerous cells (Box 2).

Cell and Gene Therapy in India

In India, the combined phenomena of allelic heterogeneity and founder effects make the genetics of many diseases highly complex. Allelic heterogeneity refers to the presence of many different mutations in the same gene that can each cause (or contribute to) the same disease phenotype. Founder effects occur when a small ancestral population carries particular disease-causing variant(s), which get amplified in the descendants due to traditional marriage practices such as endogamy (marrying within a community) and consanguinity among genetically related individuals.

The Indian Council of Medical Research’s National Registry for Rare and Other Inherited Disorders was set up in 2019 and within five years has categorised more than 15,000 registered patients.

As a result, different variants of a given disease can be found accumulated specifically in different communities, castes, or geographic regions. This means that within what looks like one disease clinically, there may be many genotypes, each possibly rare by itself. This complex landscape requires a streamlined approach to document rare genetic disorder families and their natural histories.

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)’s National Registry for Rare and Other Inherited Disorders (NRROID) was set up in 2019 and within five years has categorised more than 15,000 registered patients, of which only about 7% are receiving definitive treatment. The Ministry of Health & Family Welfare launched India’s National Policy for Rare Diseases (NPRD) in March 2021 under which several Centres of Excellence (CoEs) have been identified. These include premier government tertiary hospitals with facilities for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of rare diseases, though financial support is capped at Rs. 50 lakh. The CoEs have developed into hubs of expertise that aim to make accurate diagnosis faster and enable indigenous therapies for equitable access.

India has emerged as an active participant in the global shift toward advanced cell and gene therapies for its huge rare genetic disorder population. Here, advances in the field of oncology have helped boost capacity. A landmark achievement for cell and gene therapies in India has been the development of CAR-T cell therapy for B-cell malignancies by the Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (ACTREC) at the Tata Memorial Centre in collaboration with the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay.The indigenous CAR-T product, NexCAR19, received marketing approval in 2023 to genetically modify a patient’s immune cells to target and destroy cancer cells, at a fraction of global CAR-T prices. Several other centres such as Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore and All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi are piloting their own immuno-oncology pipelines.

Other recent examples of advancing therapeutics are equally promising and bode well for cost reduction and local access to cell and gene therapies in resource-constrained settings.

In gene therapy, India’s focus is on hemoglobinopathies, which represent some of the highest patient burdens and are supported by government-backed initiatives such as the Sickle Cell Mission. Several leading institutions are working on gene editing and lentiviral gene addition that introduce a functional copy of the gene into a patient’s cells. Pre-clinical work is underway on CRISPR-edited hematopoietic stem cells to reactivate fetal haemoglobin or correct β-globin mutations.

The first in-human lentiviral vector gene therapy for severe Haemophilia A was conducted by the Centre for Stem Cell Research (a unit of DBT-InStem) at Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, and very promising results were announced by the government in December 2024. All five adult participants in the Phase 1 study had restored Factor VIII expression and achieved an annualised bleeding rate of zero with no need of repeated Factor VIII infusions over a follow-up of nearly seven years.

Other recent examples of advancing therapeutics are equally promising and bode well for cost reduction and local access to cell and gene therapies in resource-constrained settings. The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR’s) Institute of Genomics & Integrative Biology (CSIR-IGIB) has partnered with the Serum Institute of India (SII) in November 2025 to create a public-private model to deliver its affordable, indigenous gene-editing platform for sickle cell disease.

Similarly, in cell therapies, stem cell-based regenerative approaches are developing rapidly. Pioneering work is ongoing on an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived retinal cell therapy that has now progressed to human trials. This represents India’s first scalable iPSC platform for retinal cell therapy.

These developments highlight how India is laying the groundwork for an ecosystem spanning cutting-edge science, clinical research infrastructure, regulatory clarity, and manufacturing capacity for cell and gene therapies. Such efforts have the potential to deliver affordable advanced therapies to some of the world’s largest patient populations with genetic and degenerative diseases.

The Right Diagnosis

Cell and gene therapies have demonstrated curative potential for diseases once considered untreatable, especially those caused by a mutation in a single gene where it is possible to correct the defect by replacing or editing the faulty gene sequence. In India, following the initial successes in interventions for haematological disorders, immunotherapies, and stem cell-based products, efforts are expected to increase in other monogenic disorders such as neuromuscular diseases and lysosomal storage disorders, where the number of patients is substantial.

Recent studies document how the endogamous population structure in India has amplified rare recessive alleles and multiple efforts need to be launched to identify variant propensities across the country.

The earlier cell and gene therapy is implemented the greater the chance of minimising the detrimental effects of a disease before irreversible damage can set in. Thus, programmes to innovate and implement molecular diagnostics should complement the development of cell and gene therapies in India.

Newborn screening (NBS) is an effective way of disease alleviation where babies are screened within a few days of birth, before the symptoms of the disease manifest, and early treatment is initiated to prevent morbidity and mortality. Newborn screening programmes have been very effective in some developed countries, where all babies are screened for many serious but treatable genetic disorders.

Currently, there are no uniform newborn screening strategies practiced in India. While programmes for implementing several schemes for screening and early referral are being set up, it is important to develop complementary molecular testing to accelerate diagnosis and treatment.

There is huge genetic diversity within India, with nearly 5,000 distinct population groups. Marriages among genetically related individuals can propagate disease-causing mutations established among different ethnic groups, and these can be identified by genome sequencing. Recent studies document how the endogamous population structure in India has amplified rare recessive alleles and multiple efforts need to be launched to identify variant propensities across the country. Cataloging these community-specific variations is crucial to diagnosing as well as understanding predispositions to diseases that are prevalent within population sub-groups to plan optimal therapeutic approaches.

Path Ahead

Although cell and gene therapies are being hailed as miracle cures, it can be extremely complicated to develop treatments that are personalised at the level of genes because each mutation (or variant) can have differing effects on disease severity, response to therapy, or risk of complications. Further, developing a treatment targeting just one rare mutation may help very few patients, making personalised therapies economically and logistically impractical.

Even with almost a hundred million patients nationally, there are relatively few cases per individual disorder or genotype, making trials harder and the cost per patient higher. In this context, leveraging generalised or mutation-agnostic therapies as “platform technologies” and focusing on shared pathways is a good approach for lowering the barriers to access.

Despite the costs and challenges, cell and gene therapies are the logical conclusion to end the painful suffering of patients, most often young children.

Beyond infrastructure, the success of cell and gene therapies also relies on evolving regulatory frameworks to facilitate implementation, which cannot follow the same mould as for other diseases and therapeutics. The ICMR and Department of Biotechnology (DBT) jointly issued the National Guidelines for Gene Therapy Product Development and Clinical Trials in 2019 for gene therapy work in India and to complement the New Drugs & Clinical Trials Rules that govern approval pathways.

This paved the path for developing and testing indigenous gene therapies to bring down cost as well as increase the precision of treatment in the Indian patient cohort, where the genomic variations and mutation profile can be significantly different from other ethnicities.

The DBT, with the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC), recently convened a major “industry-academia stakeholders’ meet” to chart a roadmap for advancing India’s cell and gene therapy ecosystem. In line with these policies, the research funding landscape is also transitioning from isolated pilot studies to coordinated national programmes, reflecting a move toward scalable genome engineering and locally relevant therapeutic developments.

Despite the costs and challenges, cell and gene therapies are the logical conclusion to end the painful suffering of patients, most often young children. Cell and gene therapies directly target faulty genes or cells in a way that conventional drugs often cannot and offer the hope of shifting care from lifelong maintenance to potentially durable, one-time interventions. In many diseases, a curative therapy along with supportive therapies can bring about a major difference in quality of life.

The promise remains of a single shot cure, and for some diseases at least we have reached a stage where cell and gene therapies will soon be deployed to launch a precision strike at the root cause, curing the individual for a lifetime. Truly a miracle to work towards!

Surabhi Srivastava holds a PhD from the National Institute of Immunology, New Delhi and is a molecular biologist combining over a decade of scientific research and management at the CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology. She is currently the chief scientific officer at the Tata Institute for Genetics and Society, Bengaluru.

Vasanth Thamodaran is a Senior Scientist at the Tata Institute for Genetics and Society. His work integrates CRISPR-based functional genomics, and induced pluripotent stem cells to understand inherited disease conditions and to develop platforms for therapeutic discovery.