The recent push by the Indian government for a delimitation exercise has set off waves of anxiety among the five south Indian states—Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh. Having outperformed the rest of the country in controlling their population growth, they stand to lose out relative to their north Indian counterparts when parliamentary seats and boundaries are revised to reflect population change.

Policies and programmes which improve the quality of human lives are more critical for fertility decline, rather than targeting women’s bodies.

It has been projected that with the rollout of the delimitation process, southern states could collectively lose around 20 parliamentary seats. This is in contrast to the political solution of the 1970s, when population control was topmost in policy imperatives, was to freeze the number of seats each state had. Over time, this freeze has resulted in a skewed distribution of political representation. Uttar Pradesh (UP), with a population of 240 million, has one member of parliament (MP) representing three million people, whereas Kerala, with a population of approximately 35 million, has one MP per 1.75 million people. Tamil Nadu and Kerala have, respectively, nine and six seats more than their population share ,while poorer states like Bihar and UP have, respectively, nine and 12 seats fewer than their rightful share. For many south Indian politicians, the anticipated loss of these seats is a ‘punishment’. They contend that southern states will lose representation in the parliament for having successfully implemented nationally vital population control measures; while, on the other hand, poorly performing states will end being rewarded.

To counter this, politicians in these states are urging citizens to have more children and in power, they have mulled incentives for larger families. During a mass wedding ceremony organised in October 2024, the chief minister of Tamil Nadu sarcastically suggested that couples should consider having 16 children. On another occasion, the Andhra Pradesh CM appealed to women to have at least two children to stabilise the population. The Andhra Pradesh CM also declared that the state could bring in a law that would make only those with more than two children eligible to contest local body elections. In another instance, on the International Women’s Day, an MP from the ruling party at Andhra Pradesh, offered to provide Rs 50,000 from his salary to women who give birth to their third child if it was a girl, and a cow if it was a boy.

Political anxieties notwithstanding, it is important to interrogate whether such incentives can reverse fertility decline. National and international experiences would suggest there is scant evidence that these policies would achieve their goal. On the contrary, they have the potential to erode the hard earned gains in women’s health and push the agenda of sexual and reproductive health and rights for all to a more distant dream.

Global Fertility Patterns

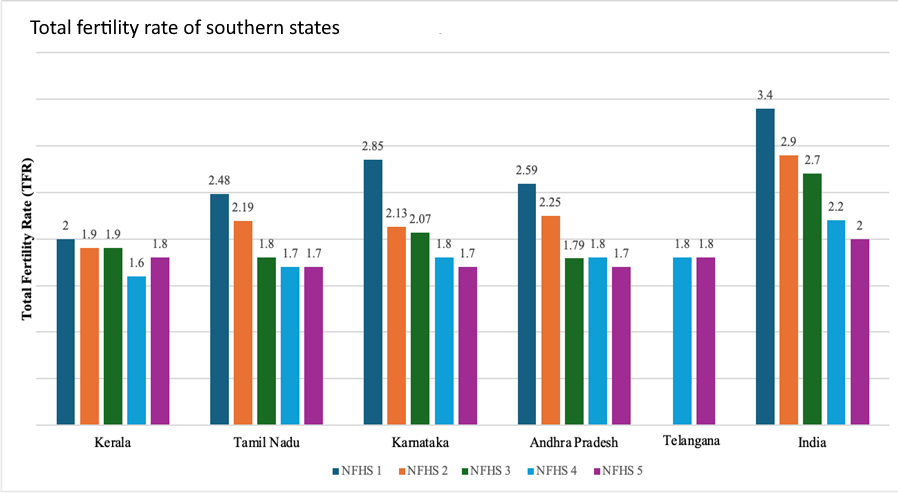

India’s southern states have a total fertility rate (TFR) of less than 2.1 which is below the replacement level, and account for 20% of India’s 1.4 billion population. TFR refers to the average number of children a woman is expected to have over lifetime, and, as such, sheds light on broader population growth dynamics. The states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu attained a below replacement level of fertility as early as the 1990s. On the other hand, TFR of north Indian states continue to remain high.

Fertility decline is a global phenomenon. As of 2021, nearly half of the nations of the world had fertility rates below replacement, and by 2100, almost every country will be in a similar place. The pattern correlates with economic development, improved living conditions, advancements in medical care, and social changes from modernisation which generate a desire for smaller families.

One of the first countries where fertility declined in modern times was France, in the mid-18th century, with the French Revolution’s sweeping social reforms. The demise of feudalism and a widespread acceptance of egalitarianism enhanced the social and economic aspirations of all classes, leading to smaller families. The pattern was repeated in 19th century England, with the Industrial Revolution. Fertility declined with increasing incomes, improved employment opportunities in the modern sectors, and a change in women’s social and economic roles. Late developing countries in Asia followed suit. The steepest decline in China occurred between 1970 and 1979, before the One-Child policy of 1980. China and Japan continue to experience fertility decline despite political urges and announcements of incentives for increased fertility.

Within India, in Kerala, while female literacy and improved healthcare facilities have been reported to be the most powerful factors contributing to the decline, the underlying reasons are larger socio-economic improvement, social justice in political and economic policies and development strategies reflected through land reforms and increased wages to workers. In the case of Tamil Nadu, the decline has been attributed to economic development, rise in consumerism and the implementation of social reforms underpinned by the Dravidian political ideology of social justice, and the influence of mass media. In Andhra Pradesh, the first state to devise a state population policy, welfare measures (PDS, ICDS, improved wages) to alleviate poverty, aided in fertility decline.

These experiences suggest that policies and programmes which improve the quality of human lives are more critical for fertility decline, rather than targeting women’s bodies. In other words, fertility decline should be the means to an end, namely improved human lives, and not an end in itself.

India was one of the first countries to launch the National Programme for Family Planning premised on the argument that fertility control was inevitable for economic development. Although the experiences from other parts of the world clearly demonstrated that fertility decline was a function of varied demographic, social, economic, and political conditions, the post-independent Indian state shifted the onus onto women by problematising high fertility as an issue of ‘women having too many children’.

Policies and interventions, relying on political rhetoric and incentives, that do not take into account the existing evidence on fertility control are destined to fail.

Smaller families became, as it were, the responsibility of women, compromising their sexual and reproductive rights. With little confidence in reversible methods which required a supportive health system, the go-to solution was sterilisation after achieving the desired family. Early sterilisation was touted as an empowering step for women allowing them to pursue higher education and careers in the post-childbirth phase, even though the limited evidence contradicts this. (A related consequence is the increasing prevalence of sterilisation regret reported among married women and the higher risks for sterilisation failure, ectopic pregnancies, menstrual cycle changes and future risk of hysterectomies among sterilised women.)

The Missing Women

Decades of research have shown that high fertility is detrimental to women’s health contributing to higher rates of maternal mortality and morbidity. Yet, India’s approach was never premised on women’s health, as a result of which fertility decline was achieved without any significant improvement in their health, including sexual and reproductive rights. India continues to record high maternal deaths - in 2023, 19000 maternal deaths were recorded. Multiple pregnancies is one of the significant risk factors for cervical cancer, which is the second most common cancer in India, in both incidence and mortality. Iron deficiency and anaemia, highly prevalent in women with multiple gestations, affects about one-half of pregnant women in India. These indicators reflecting the continued neglect of women’s health in India is also mirrored in the history of our fertility control measures.

The targeting of women’s bodies merely as a site to enact development agenda aligns with the poor focus on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in national health policies and programmes. As per the data from National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5; 2019-2021) a significant proportion of Indian men (as high as one in two men from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Telangana) reported that “contraception is women’s business and a man should not worry about it” . This is also aligned with the relatively lower usage of condoms and consistently low proportion of vasectomy. Even in states with high human and gender development indicators like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, women face constraints in negotiating sexual and reproductive choices like contraception, which is founded in poor knowledge, mistrust and misconceptions. A recent Kerala-based qualitative enquiry into abortion access, reported that healthcare workers identified family planning as an inevitable measure for “population control” and “for healthier future generations”, completely missing women’s health as a priority.

It is now clear that state interventions which are solely focusing on pushing women to have more or less childbirths have a limited effect on fertility. Hence, policies and interventions, relying on political rhetoric and incentives, that do not take into account the existing evidence on fertility control are destined to fail. This is further concerning given the global rise in far-right fundamentalist positions to prominence, catering to regressive ideologies which reduce women to reproductive machines.

This article has been published under the Appan Menon Award 2025 received by the Vichar Trust from the Appan Menon Memorial Trust.

Malu Mohan is a senior researcher at Women’s Institute for Social and Health Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. Sapna Mishra is an independent public health researcher.