India plans to hold a Census in 2026, followed by a redrawing of parliamentary constituencies, known as delimitation. This move has angered the southern states, as the process could sharply change the balance of political representation between the northern and southern regions in the parliament.

If delimitation takes place in 2026, the northern states—especially Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan—are expected to gain 31 seats in the Lok Sabha. Currently, the Lok Sabha has 543 seats. Meanwhile, the southern states—particularly Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Andhra Pradesh—will lose 26 seats.

In response, Tamil Nadu’s Chief Minister M.K. Stalin convened an all-party meeting on 5 March 2025. Leaders from across the state were united in their opposition to the proposed delimitation. They described it as a deliberate attempt to undermine their “political relevance”. Stalin argued that if delimitation is based strictly on population figures, it will penalise the southern states for successfully reducing their birth rates. Conversely, it will reward the northern states for failing to do so.

The chief ministers of Karnataka, Telangana, and Kerala have warned that the south’s weaker presence in parliament would lead to lower central allocations. They argue that this would deepen existing divisions between the northern and the southern states. Even Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu, an ally of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has voiced his concerns. This was despite union home minister Amit Shah’s assurance that, after delimitation, “not a single seat will be reduced in any southern state” on a pro rata basis.

…[T]he North-South divide now goes beyond the question of seat numbers. Southern states are demanding a larger role in national policy-making, fiscal equality, and greater federal autonomy.

The upcoming delimitation has sparked debate and led to calls for revising the process (Rangarajan 2024). However, the north-south divide now goes beyond the question of seat numbers. Southern states are demanding a larger role in national policy-making, fiscal equality, and greater federal autonomy.

Delimitation can no longer be viewed simply as a constitutional adjustment of constituencies for political representation. It must be understood within the broader context of federalism. Parties that control the central government and hold power in the northern states have shaped the functioning of the federation.

An additional source of tension is the ideological gap between northern and southern states. The ideology of Hindutva, for example, faces “regional limits” and is less accepted in the South (Chatterjee 2019). Southern states, especially Tamil Nadu, are also unhappy with the central government’s efforts to abolish the three-language formula and “impose Hindi” on them.

From an economic perspective, the imbalance between the two regions is troubling. The southern states contribute 31% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP), while the northern states account for only 24%. Since liberalisation in 1991, the South has consistently outperformed the North, resulting in per capita incomes that exceed the national average. The South is also the most industrialised part of India, with a strong emphasis on high-value industries. In contrast, the North relies heavily on agriculture and lower-value manufacturing.

Despite these facts, there is a growing perception since 2014 that the fiscal space available to the smaller southern states—most ruled by opposition parties—has diminished. If representation shifts without taking economic contributions into account, tensions around fiscal federalism could intensify.

Reorganisation of states around linguistic identities in the mid-1950s led to significant imbalances in the size of Indian states—a problem that affects today’s delimitation process (Bondurant 1958). It is worth recalling that B.R. Ambedkar’s ideas about providing equal representation to states, aimed at creating federal balance, were overlooked in 1956. Violent protests over linguistic reorganisation were partly responsible. Much has changed in India since then, and revisiting Ambedkar’s perspective could enrich the ongoing debate over delimitation.

Such a discussion is timely because the reorganisation of states remains incomplete in post-independence India. Still, our analysis highlights serious challenges in today’s political climate. Implementing Ambedkar’s suggestion of creating smaller states to achieve a more balanced federation faces significant practical limitations.

Ambedkar’s Ideas

Before the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC) released its report in September 1955, Ambedkar generally agreed with Congress Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (this section draws on Pai and Kumar 2014). Both believed that creating large states would be the best approach, as these blocs could undertake efficient planning of scarce resources. However, after reading the commission’s report, Ambedkar reconsidered his position.

In a December 1955 pamphlet, Thoughts on Linguistic States, Ambedkar highlighted the uneven sizes of states proposed by the commission. According to the recommendations, eight states—Rajasthan, Punjab, Orissa, Kerala, Karnataka, Vidharbha, Hyderabad, and Andhra—would each have populations between 10 and 20 million. Four states—Madhya Pradesh (MP), Madras, Bengal, and Bihar—would have populations between 20 and 40 million. Bombay would become a state of 40 million, while Uttar Pradesh (UP) would have more than 60 million.

Ambedkar warned that the commission’s decision to consolidate northern India into large states, while dividing the south into smaller Dravidian states, had created a North-South divide.

Ambedkar proposed a solution that balanced both linguistic and size considerations. He suggested dividing large mono-linguistic states into smaller ones, with more than one state sharing the same language. This would fulfill cultural aspirations and also create states of a more reasonable size.

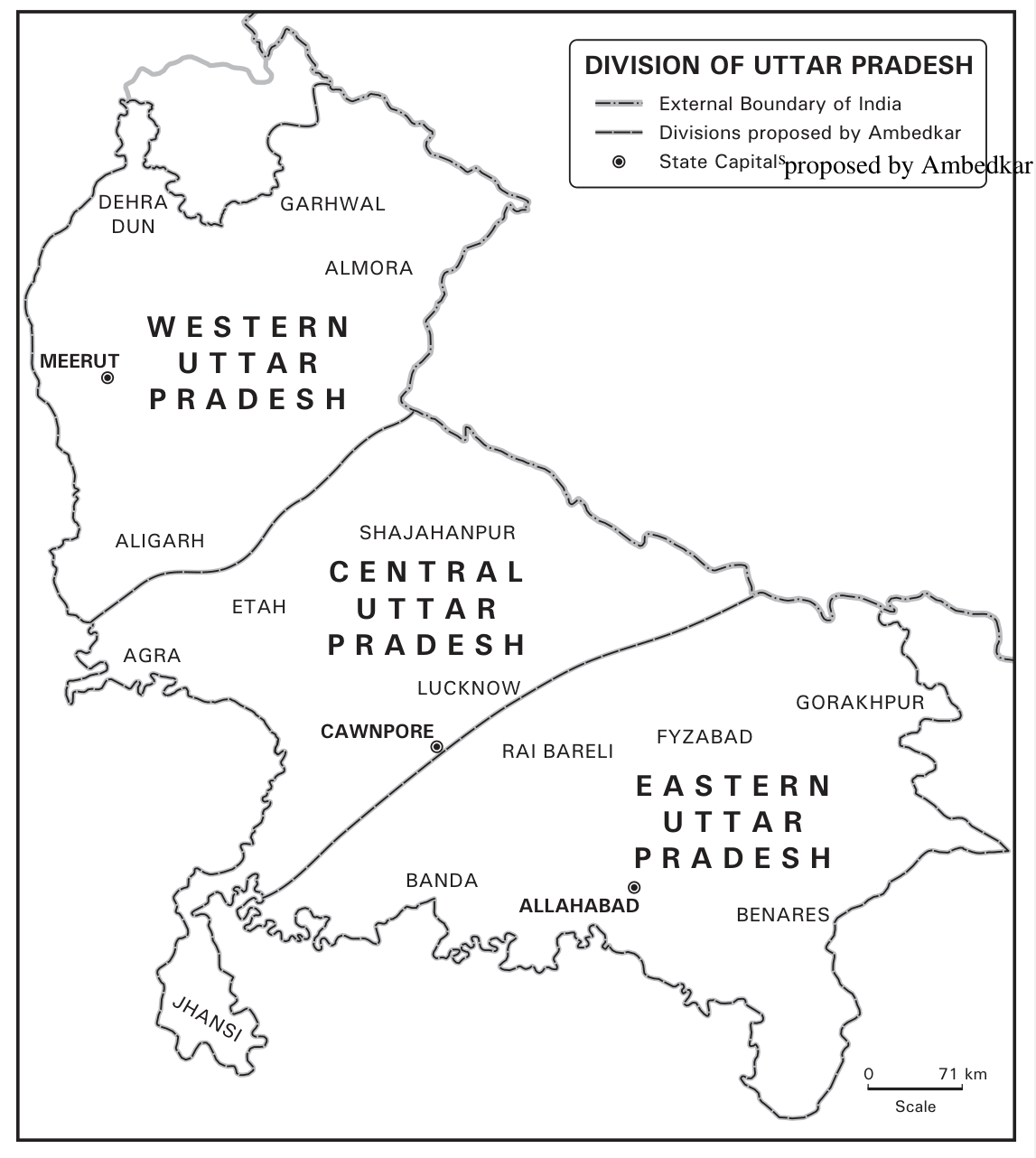

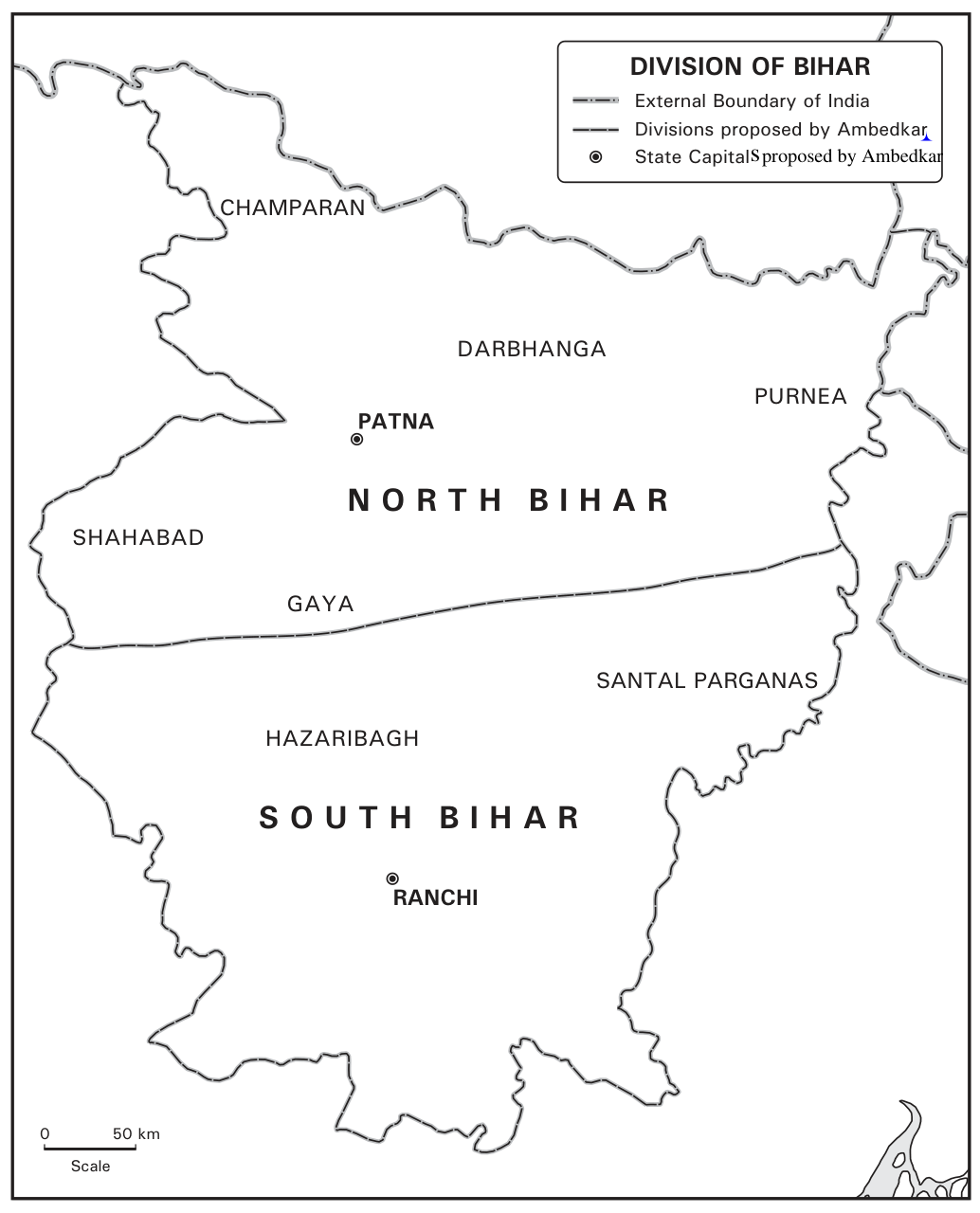

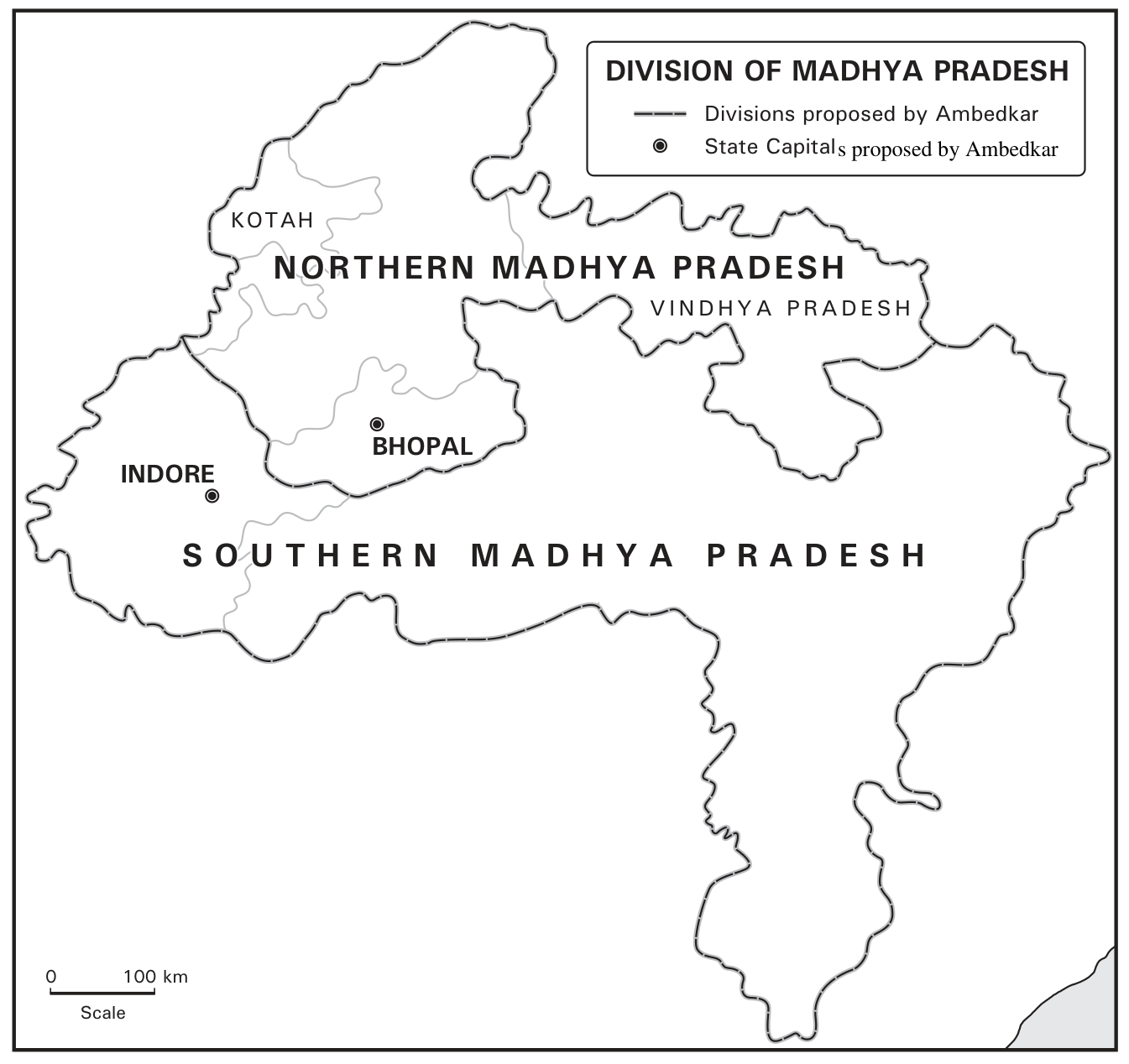

Focusing on the division of three large states in the North and Maharashtra, Ambedkar advocated splitting Maharashtra into four states, all Marathi-speaking—Maharashtra City State (Bombay City State), Eastern Maharashtra (Vidharbha), Central Maharashtra (Marathwada), and Western Maharashtra (Konkan and Desh). He also proposed dividing UP into three regions—Western (Pachim), Central (Awadh), and Eastern UP (Purvanchal). Bihar and MP would each be split into North and South. All these divisions would be along linguistic lines, with the new states speaking Hindi.

Ambedkar noted that K.M. Panikkar, a member of the commission, had argued in his dissenting note for dividing UP in a similar manner. Ambedkar supported his proposals with maps and detailed data on the potential states’ area, population, budgets, and capitals.

Map 1: Ambedkar's Proposal for Division of Uttar Pradesh

Map 2: Ambedkar's Proposal for Division of Bihar

Map 3: Ambedkar's Proposal for Division of Madhya Pradesh

Source for all maps: Prepared by the author based on a map in Ambedkar 1955 and 1979. Ambedkar (1955 ) refers to Ambedkar’s Thoughts on Linguistic States. Ambedkar (1979) refers to Vasant Moon (ed.), Baba Saheb Writings and Speeches.

In his alternative plan for reorganisation, Ambedkar proposed several key features aimed at creating a more balanced and democratic federal system. He argued that viability should be the guiding principle, encompassing dimensions like equality of size and the relationships between states.

Ambedkar stressed the importance of economic feasibility. Each province, he said, should have enough revenue to support effective governance. He cautioned against establishing provinces just to fulfill the ambitions of a few individuals seeking leadership roles.

According to Ambedkar, equality among all citizens would be easier to achieve in smaller states. Large states, by contrast, risked allowing a “communal majority” to dominate linguistic or socially disadvantaged minorities, such as the Scheduled Castes. He also noted that, in large states, one or two castes often hold dominance. For instance, Jats are predominant in Punjab; Kammas and Reddys in Andhra Pradesh; Lingayats and Vokkaligas in Karnataka; and Marathas in Maharashtra.

To address potential issues arising from linguistic divisions, Ambedkar emphasised that it was important to prevent conflict between the national language and the official language of each state.

These divisions mostly responded to long-standing demands to protect distinct hill or tribal identities and needs. They also reflected concerns over lack of resources, regional neglect, and economic backwardness.

Ambedkar warned that the commission’s decision to consolidate northern India into large states, while dividing the south into smaller Dravidian states, had created a North-South divide. This arrangement gave the northern states greater influence in parliamentary decision-making. He noted that this led to mutual suspicion and even hints of possible separation, as cultural differences between the two regions were, in his words, “very combustible”.

Ambedkar reported a concern expressed by C. Rajagopalachari—there was a widespread fear that the prime minister would always come from the northern Hindi-speaking region. There was also anxiety about UP dominating national politics, which prompted numerous petitions to the commission.

On 28 September 1955, Krishna Menon wrote to Nehru suggesting the creation of “a Southern State, a Dakshina Pradesh, as a corollary to UP, which could include the present Tamil Nadu, Travancore, Cochin, Malabar and possibly Kanara up to Kasargode”. Ambedkar thought Hyderabad should be chosen as the capital, since it was centrally located in India and already had suitable buildings for government offices.

Ambedkar further argued that linguistic states would gradually become more homogeneous, but new sources of conflict would probably emerge. Differences in historical backgrounds, state size, economic development, and governance—such as those seen in the 2014 split of Andhra and Telangana—could become divisive.

Finally, Ambedkar criticised the Rajya Sabha for failing to provide equal representation to each state. This, he believed, could lead to discontent among the smaller states in the South and in the North-East.

Creating Smaller States

State reorganisation continued in India after independence. Maharashtra and Gujarat were created in 1960, followed by Nagaland in 1963, and Haryana and Punjab in 1966. New states were also formed in the North-east during the 1970s.

But, it was only in 2000 that the eastern part of MP was separated to form Chhattisgarh. In November 2001, the large states of UP and Bihar were divided, creating Uttarakhand and Jharkhand. In June 2014, Telangana was carved out of Andhra Pradesh. These divisions mostly responded to long-standing demands to protect distinct hill or tribal identities and needs. They also reflected concerns over lack of resources, regional neglect, and economic backwardness.

The Congress, which had passed a resolution in 2001 to establish a second States Reorganisation Commission to consider creating smaller states, did not follow through.

The breakup of these states rekindled demands for further reorganisation in many areas, especially in the two large states of UP and Maharashtra. In UP, there was a renewed demand for division into four states—Harit Pradesh in the western region, and Awadh, Purvanchal, and Bundelkhand. These demands dated back to the 1930s, and resurfaced in the 1960s and 1990s, but no major agitation for it occurred in the 2000s (Jagpal Singh 2001).

In Maharashtra, the central government’s consideration of the Telangana issue in 2011—and its eventual success—helped create a favourable political environment for the division of Vidharbha. This led to a strong agitation in 2010, with many pro-Vidharbha organisations and several Congress leaders supporting the cause.

The longstanding demands to divide UP and Maharashtra—which Ambedkar strongly supported—remain unmet due to political developments in recent decades. One major reason is the rise of fundamental identities based on caste and religion. These identities have overtaken regional identities and united significant sections of the population. Another factor is the reluctance of political parties. They fear losing their strongholds in these large states, which would also weaken their position in the central government.

In UP, identity politics surged during the 1990s. Political parties such as the Samajwadi Party (SP), Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), and BJP built large vote-banks across the state. The SP and BSP focused on Dalit assertion and Other Backward Classes (OBC) reservations, especially after the Mandal Commission. The BJP, led by upper castes, mobilised support around the Ram Temple agitation. These movements sidelined the idea of reorganising the state.

When identity politics began to fade, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government approved the creation of a separate Telangana state in 2013. BSP President Mayawati then urged the central government to split UP into four states. Her government had made a similar proposal in 2011.

However, the Congress, which had passed a resolution in 2001 to establish a second States Reorganisation Commission to consider creating smaller states, did not follow through. The party repeated this promise before the 2008 Lok Sabha and 2014 Andhra Pradesh assembly elections. Nevertheless, after winning the 2004 general election, the Congress abandoned the commitment.

Meanwhile, with the resurgence of the BJP under Narendra Modi and its victories at the centre in 2014, and within UP in the 2017 and 2022 assembly elections, the party has shown no interest in dividing a state that sends 80 members to parliament.

Responding to Mayawati’s renewed demand in 2025, UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath said, “Uttar Pradesh is Uttar Pradesh in itself and this is its potential. I think Uttar Pradesh should achieve its goals by staying united... That is its strength …, its identity, and its respect”.

In Maharashtra, the movement for a separate Vidharbha state gained significant momentum but eventually faded. This was because senior BJP leaders, such as Devendra Fadnavis, did not take any action on the issue after their party came to power in 2014, despite earlier promises to consider the demand. The rise of the Shiv Sena and, more recently, the reservation movement led by Jarange Patil, has reshaped Marathi identity and pushed regional aspirations like Vidharbha statehood to the background.

Our analysis suggests that unless the large states in the Hindi-speaking heartland and western India are divided … achieving genuine equality within the federation will remain out of reach.

During the 1960s, the Shiv Sena popularised the ideology of “Nativism” (Gupta 1980). It capitalised on anxieties about employment, Marathi language, and culture among Mumbai’s middle and working classes. In the 1980s, the party shifted its ideological focus to Hindutva—a political ideology based on Hindu identity—and, after its victory in the 1987 elections, established strongholds across Maharashtra. This ideological change enabled the party to form a long-term alliance with the BJP, which remains opposed to dividing the state.

From 2023 onwards, Jarange Patil’s reservation movement has further strengthened Maratha identity. Moving away from the older image of the Maratha as only a warrior group, Patil has redefined the relationship between the Kunbi and Maratha communities. He advocates for the economic grievances of both as a single group, seeking reservation eligibility for them under a united identity.

In September 2025, there was an assurance that Kunbi status would be granted to eligible Marathas after careful verification. It remains uncertain whether this promise will be successfully implemented. Given the current political atmosphere, it now seems unlikely that either UP or Maharashtra will be reorganised into smaller, more manageable states.

Our discussion highlights several historical and structural problems that stem from the reorganisation of states by the States Reorganisation Commission in 1955. These issues continue to shape the current debate over delimitation. The delimitation exercise in 2026 is likely to place the southern states at a distinct disadvantage in terms of political representation, further deepening the divide between the North and South.

In this context, Ambedkar’s proposal to create smaller states is still highly relevant. Smaller states would help ensure fair representation and balance within our federal system. Such a reform would promote parity in representation, fiscal equity, an equitable role in decision making, and a perception among citizens that they receive a fair share of resources and power. Only with such changes can genuine cooperative federalism become possible.

Nonetheless, reorganising the states into smaller units faces significant practical challenges. Our analysis suggests that unless the large states in the Hindi-speaking heartland and western India are divided—a demand that has resurfaced from time to time—achieving genuine equality within the federation will remain out of reach. Delimitation therefore continues to be a complex and contentious issue, with no easy solutions in sight.

Sudha Pai retired as professor of political science at Jawaharlal Nehru University.