A surreal application form for a residence certificate filled in the name of ‘Cat Kumar’, next to a photo of a grumpy feline, went viral recently, even attracting a police case. This form, while intended as a farcical response to the documentary mandates of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar, speaks not only to the absurdity but also to the extraordinary expectations of the exercise.

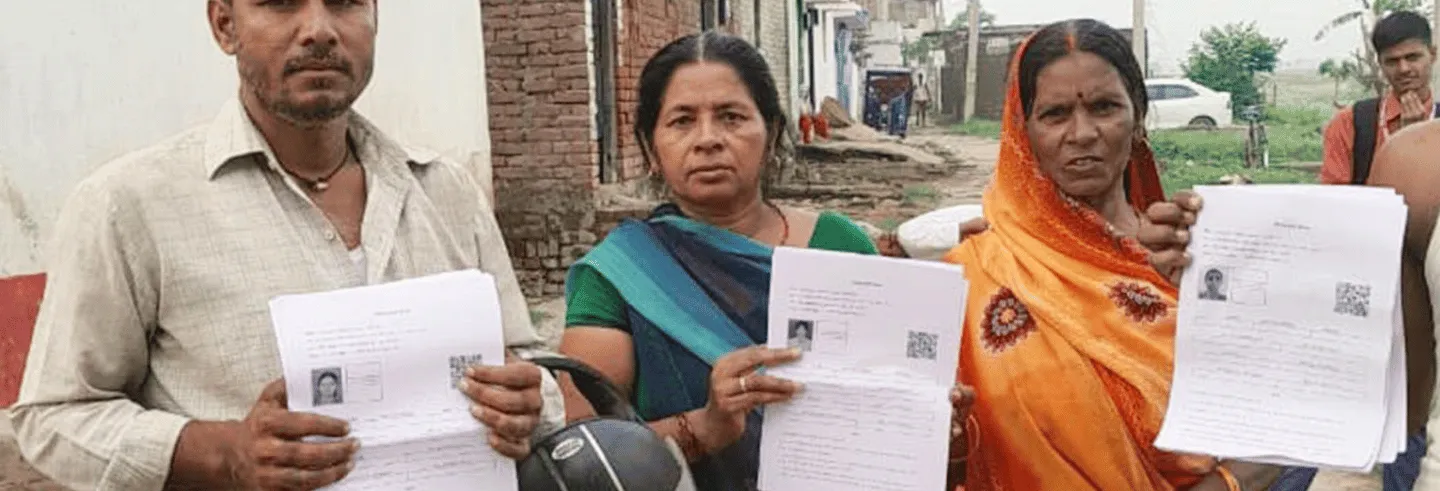

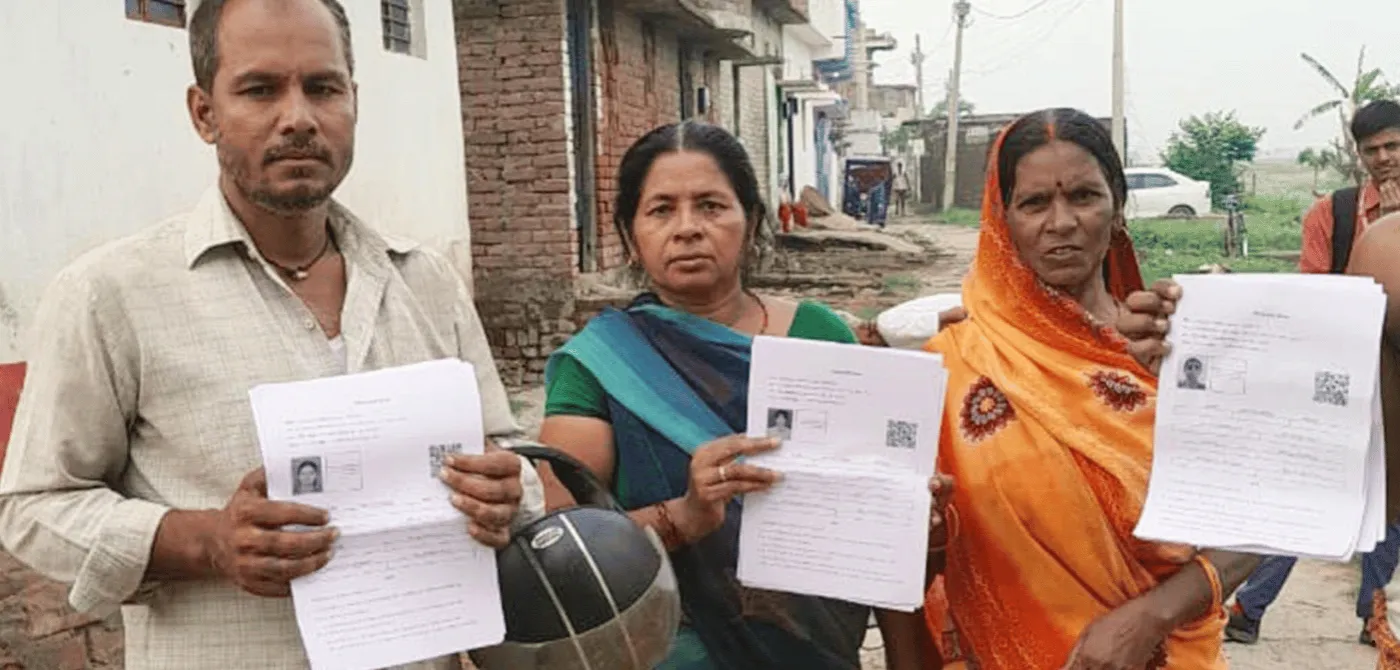

In the ongoing discussions on the SIR, an argument on document scarcity is becoming hegemonic. This is the belief that people do not possess the documents in the list of 11 IDs prescribed by the Election Commission of India (ECI).At one point, it was stated that if voters were able to prove that they were included in the 2003 electoral roll, they would be exempted from producing any of these documents. From surveys to jansunwais to op-eds to ground reports, a vast literature has now been built up that is aimed at proving how and why these newly-prescribed documents are not in the possession of most. This literature has done vital work in showing how disenfranchisement is working and why the SIR is such a dangerous exercise.

Documents and IDs have assumed monstrous powers over marginalised lives, and the state is going further and further down the path of sorting out who can and cannot belong in New India.

At the very same time, we are concerned that an excessive focus on document scarcity in discussions on the SIR can come to function as a red herring. What also needs to be centred is that the SIR is a never-before-seen bureaucratic narrowing down in how voters get to stay on the electoral rolls, a move that is making – or could potentially make – identification an impossibility for almost anyone.

A singular or overwhelming focus on how people don’t hold the required documents can keep one from noting how citizenship and belonging are being reformulated bureaucratically and through seemingly routine procedures—such as revision of electoral rolls or the (re-)institution of a registry of citizens—in line with the majoritarian politics of ‘New India’. The increasing impossibility of being firmly and fully identified is leading to the creation of a new form of what we term extraordinary citizenship, a category of Indians who have ticked every box of proving their belonging and their right to vote not just in the documentary and procedural senses but also socially, politically and ideologically.

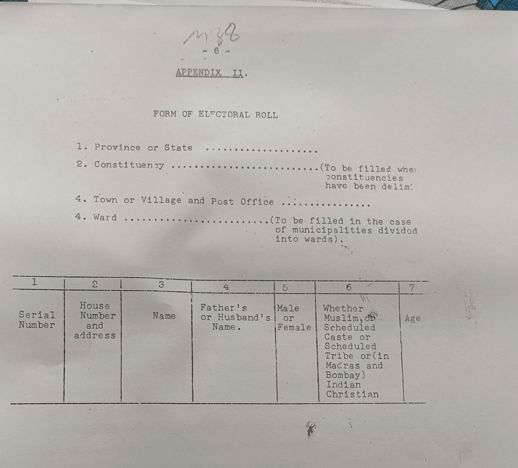

(Source: File no. 6095/46 (2). Political and Services Dept, H Branch, Maharashtra State Archives, Mumbai.)

Our own fieldwork on documents and IDs in very different parts of north India—urban and rural, across Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand—has revealed to us that poor and marginalised groups hold a treasure trove of documents, perhaps more carefully than the better off because the poor know how much of their lives are tied up so critically with the possession of these pieces of paper. Even so, one might hold a plethora of commonly respected IDs, yet they are no guarantee of being acknowledged as a ‘true Indian’, as the many cases of suspected ‘Bangladeshis’ or attacks on minorities across India starkly show. In short, IDs and papers are losing the power to protect and prove identities.

This is the central paradox in the present-day Indian state, which the document-scarcity narrative entirely misses and, in fact, can inadvertently cover up: On the one hand, there are stricter and stricter injunctions to provide documents to prove something – from whether you are entitled to welfare benefits to whether one can vote or, even, if one is a citizen. On the other hand, even if one possesses all these documents and has managed to procure IDs, they still don’t entitle one to belong to New India. It isn’t just the paper state that is the Indian state that is slowly but surely changing, but also the always-fragile protections these pieces of paper once lent its citizens. Your ‘true’ Indianness, as the Supreme Court recently remarked of the Leader of the Opposition in India’s Parliament, will always be suspect, no matter how documented and ID-ed you are.

Bureaucratic Narrowing

‘Identifying’ a person as a ‘bona fide refugee’, a voter as a legitimate ‘ordinary resident’, a ‘household consumer’ as the rightful ration card holder are all processes marked by complex and frustrating pasts. Inclusive outcomes have resulted not just from political patronage and canny middlemen who have aided the poor in securing documents. Rather, they have resulted from a deeply democratic imagination of ‘who belongs’, marked by meaningful reciprocities between the enumerators and the enumerated, as well as bureaucratic latitude and openness to engage with complex manifestations of residential circumstances. The ‘enumerated’ spoke through a rich panoply of their own, albeit not always inclusive and unitary, voices expressed through unions, refugee associations, caste associations, community-based organisations, to cite a few.

We are entering a dark new terrain where the voice of the voter becomes something to be legally proven with a never-before-seen stringency...

The stringent nature of the documents mandated by the current SIR exercise—especially those like passports, matriculation certificates, caste certificates, permanent residence certificates, and pension payment orders—betrays a strong elitist bias of presuming literacy, income status, caste agency, access to local bureaucracies, and middle-class employment. They fly in the face of the original social contract of the equality of all electors. In his radio broadcast to the nation on 21 March 1951, the first Chief Election Commissioner of India, Sukumar Sen, declared, “Every citizen counts equally with every other citizen according to our Constitution, and each one must have an equal voice in the election of the members of the House of the People”. 1Broadcast by All India Radio (Delhi station) titled ‘General Elections – Democracy’s Biggest Experiment’, 26 March 1951. In File No. 8030/46 (3), 1951. Political and Services Department, H Branch. Maharashtra State Archives (MSA), Mumbai.

The various norms of identification prescribed over different elections were broadly aligned with this sentiment. A whole corpus of work on the historical making of the democratic vote has shown that there was a capaciousness in the early procedural imagination of the EC in terms of which documents were allowed as proof of identity to register as a voter in newly independent India (Shani 2018; Roy and Singh 2019). Where there was a deletion of 25 lakh women—10% of the total electorate—in the first national election, because they used their male relatives’ names instead of their own names, Sen noted with appreciation the protests of women’s organisations across different states, and hoped to include them in the next annual revision. 2Broadcast title ‘28,000 women off the electoral rolls’, 2 August 1951. In File No. 8030/46 (3), 1951. Political and Services Department, H Branch, Maharashtra State Archives (MSA), Mumbai.

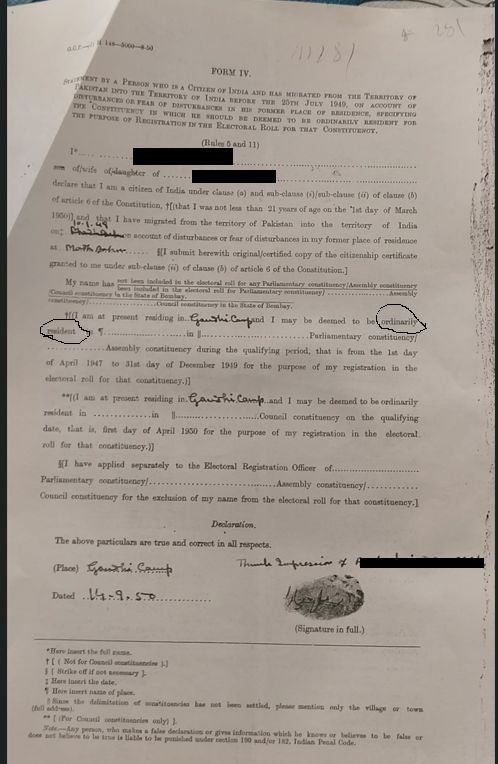

The Constituent Assembly Secretariat, the authority in charge of preparing the first electoral rolls of the country, worked with provincial governments and refugee associations to admit an impressive cornucopia of conventional and makeshift documents as well as extra-documentary forms such as municipal certificates, police birth registers, age certificates, refugee declarations and horoscopes. In complying with CAS instructions, regional administrations sought additional circle and revenue staff to be able to increase their capacity to identify ever-expanding refugee voters and revise rolls. The Political and Services Department, the Collectorate of Bombay and Poona, and the Commissioner for Greater Bombay Municipality were in conversation with each other to determine special procedures for ‘wandering tribes’ to ensure that they were both identified and not counted twice. 3See File No. 2124/46 – B, Part II. Political and Services Department, H Branch. Maharashtra State Archives, Mumbai.

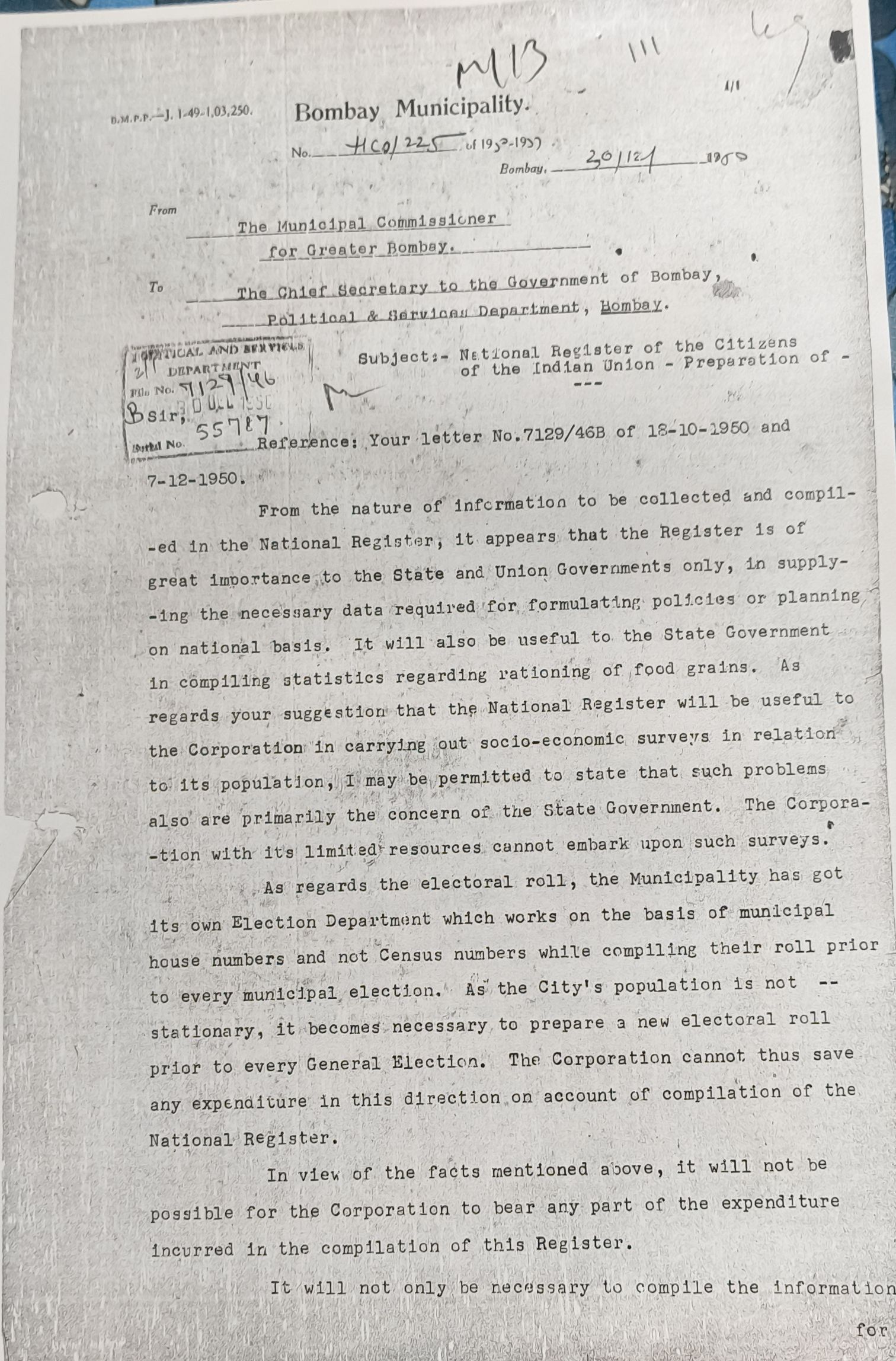

(Source: File no. 7129/46 – I. Political and Services Department, H branch, Maharastra State Archives, Mumbai.)

More relevant for our present times, efforts were made to free the franchise of constricting cross-verifications. While there were several discussions as early as 1950 of tying electoral rolls to a National Register of Citizens, the country, the plan was eventually abandoned. 4See, for example, Gopalaswami, Registrar General, to Ministry of Home Affairs, Office of the Registrar General, 11 April 1950. Letter No. 290/50-RG. In File No. 7129/46-I, Political and Services Department, H Branch. Maharashtra State Archives, Mumbai. Authorities like the Commissioner for Greater Bombay Municipality pointed out that the NRC might be useful for food policy but definitely not for preparing electoral rolls, and clearly implied that it was wrong to conflate socio-economic surveys with election surveys. Municipal Commissioner B.K. Patel wrote that voting populations were not stationary, and that census data could not replace door-to-door house surveys to register people on rolls, as each election demanded a fresh headcount. 5Municipal Commissioner for Greater Bombay, to the Chief Secretary to the Government of Bombay (Political and Services Department, Bombay), 30 December 1950. Letter No. HCO/225. Political and Services Department, H Branch, File No. 7129/46-I. MSA. Patel was also not interested in squandering the strained financial resources of the municipality for sharing the costs of carrying out this exercise with the Bombay government. The Bombay Collector’s office noted about censuses in general (though not the NRC) that they were useful for logistical purposes such as noting house numbers, but relying on an inert and fixed head count would imply ignoring demographic change, building demolitions and additions, and the criticality of face-to-face interactions with enumerators. 6See Collector of Bombay to the Chief Secretary, Political and Services Department. 9th February 1948. Letter no. ADM/236. In File no. 2124/46 – B, part II, Maharashtra State Archives, Mumbai. While the Collector’s office was referring to the 1941 census, the Municipal Commissioner’s office specifically objected to the NRC. Letter No. HCO/225.

The ‘Ordinary Resident’

The electoral regime was not tied down to paper and inert procedures. It was instead characterised by a laudable anxiety and democratic imagination to ensure that they planned for voters’ adversity, precarity, dispossession, and even emotional ties. This inclusive imagination becomes clearer when we turn to the frameworks that the Election Commission historically used to admit the widest possible definitions of ‘ordinary resident’.

In the 1994 Dr Manmohan Singh vs. the Election Commission of India judgement, the Guwahati High Court defined the term ‘ordinary resident’ to mean ‘a usual and normal resident of that place, residence must be permanent in character and not temporary or casual, and it must be for a considerable time’. 7See both the 2016 and 2023 manual. While the EC manuals on electoral rolls of 2016 and 2023 reiterated this definition and put a premium on the concept of ‘permanent residence’, this was presented as an idea rather than a total administrative fact.

The current EC exercise seems light-years away from all these instances of democratic expansion.

In its 2016 manual, the Election Commission permitted several options to prove ordinary residence, including bank passbooks, ration cards, and even letters through the postal department, and admitted a reflexive and discretionary set of options to determine their age, including oaths by parents and ‘gurus’ for third gender, and declarations of age by the candidates themselves. 8Election Commission of India, Manual on Electoral Rolls, October 2016: Document 10, Edition 1.

Yet, the EC did not strictly consign Booth Level Officers to these documentary fiats. A wide-lens approach to this is clear when the 2023 EC manual considered verifying homeless persons, sex workers, migrant workers, but fascinatingly, overseas residents too. BLOs were expected to rely on sensible discretionary practices where documents could not be produced, including checking if a homeless person continued to sleep at night in the same place. The 2023 manual also did away with an earlier requirement of 180 days of residence to be eligible for the ‘ordinary resident’ status; now the ERO, as well as the BLO, were required to “determine a question as to where a person is an ordinary resident”.

Even in the extreme case of the overseas Indian resident, who clearly was non-resident in India, the Election Commission was bound by a 2010 amendment of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, which entitled non-residents to be counted as voters as long as they retained their Indian citizenship.

(Source: File No. 2124/46- B, Part II. Political and Services Dept, H Branch, Maharashtra State Archives, Mumbai.)

Finally, let us consider a 2022 proposal of the Election Commission which was aimed squarely at ‘improving voter participation of domestic migrants using remote voting’. 9B.C. Patra, Secretary to the Election Commission of India, New Delhi, to President/Chairperson/General Secretary of all National/State Political Parties, 28 December 2022. Letter no. 51/8/16/RVM/2021-EDPS This was aimed at migrants who did not enrol themselves in the electoral rolls of ‘their place of work’ because they had shifting residences, strong emotional connections with their home state, or also because they feared deletions from their home rolls could impair their possession of property. The EC considered using a ‘multi-constituency remote EVM’ which would capture votes cast from multiple constituencies in a single remote polling booth. This was a radical proposal not on account of the nature of the ostensibly tamper-proof, remote voting technology that was meant to be used, but because of the deep commitment to record the vote of the itinerant ordinary residents. 10This proposal was incentivised by the 2015 Supreme Court order in Dr Shamsheer VP vs Union of India which had asked the EC to look at options of remote voting for domestic migrants.

The current EC exercise seems light-years away from all these instances of democratic expansion. As Ashok Lavasa, a former election commissioner, has noted, the ECI has “chosen to adopt a procedure that has no precedence and little logic” with its insistence on “acceptable documents” (read scare quotes). He poignantly asks if the right to vote can be reduced to a driving license that needs to be renewed from time to time.

Belonging in New India

We are entering a dark new terrain where the voice of the voter becomes something to be legally proven with a never-before-seen stringency, not only in the formally stated process but also in spectral (unofficially and informally accepted) procedures.

For the SIR, the BLO is informally encouraged to draw up a "family tree" of voters where the latter are asked to trace their relatives in the 2003 electoral roll, in which case, they could be exempted from producing other documents. If this sounded like a welcome albeit arbitrary workaround, impossible expectations figure here too in terms of asking the applicant to furnish the polling booth numbers of where, say, a grandparent voted in the 2003 election. This conjures what the anthropologist Nafis Aziz Hasan termed "citizen labor" – where people are increasingly called upon to make complex diagrams of their own identity and produce elusive annotations to clarify them.

What if it isn’t about documents—acceptable or scarce or otherwise—but about something else altogether?

The politics of New India has entailed absorbing and optimising some of the most patriarchal, communal, and casteist residues of the older documentary regime.

Putting aside vote-chori claims by the Congress for the time being, what if the revisions to the electoral rolls actually signify something else that we are seeing across the state, just in a different guise: who can belong and who cannot in New India? The starkest example of this is the recent crackdown on Bengali-speaking migrants across India. Bengali migrants have been detained in Rajasthan, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh, and recently, several have left Delhi and Gurugram before they were accused of being ‘illegal’ Bangladeshis. Several cases of forced deportations to Bangladesh – what is often described as being “pushed across the border” - of individuals who hold the correct documents are also coming to light.

In short, being documented or holding the correct papers – including the much-vaunted ID, Aadhaar – doesn’t anymore qualify you for Indian citizenship or protect you from violence. We are seeing the creation of a new category of the citizen who is always suspect because of caste, class, gender, name, language, and occupation; even speech, dress, and deportment. This figure stands apart from the extraordinary citizen who has not only achieved the near-impossible feat of possessing all the documents—and, hence, the correct ID—but also exhibits the acceptable characteristics of belonging to ‘New India’. The extraordinary citizen must not only produce squeaky clean documents at every fresh challenge by the state—in this case, of voter identity—but also be immediately ticking the boxes of ‘suitability’ and ‘respectability’.

It is critical for this potential extraordinary citizen to speak in an unsuspicious privileged caste or communal language. Nari Kamakshi recently wrote about her experience of being denied a passport through the lens of being the daughter of a devadasi woman. Her story demonstrates the working of institutional gatekeeping norms of caste and patriarchal violence. A recent rush for Matua cards – or “Hindu” card/certificate – about 90 km from Kolkata shows the visceral nature of the fear that the SIR is coming to other parts of India, whereby people, in this case Dalit communities, are being incentivised to secure documentary proof of being Hindu.

A Terrifying Temporality

The politics of New India has entailed absorbing and optimising some of the most patriarchal, communal, and casteist residues of the older documentary regime. What now needs to be highlighted is the violence of state-sanctioned identification apparatuses with both the NRC and the SIR, and crucially, how this violence is coming into force through seemingly mundane bureaucratic shifts. With both the NRC and SIR, there is a move to render all exercises of identification into punitive ones, where even the erstwhile, always-fragile protections afforded by holding certain papers or IDs are dissipating.

The NRC in Assam was meant to serve as a legal record of the rightful citizens of the state. The implications of not being included were terrifying, as they entailed the excluded person being declared a foreigner and locked up in a detention centre. In Assam, the update of the NRC relied on 'legacy data' from the 1951 NRC and electoral rolls up to March 1971, which were fed into networked databases and made searchable through unique legacy codes. The Comptroller and Auditor General found several shocking, haphazard aspects in this digital infrastructure, from arbitrary vendor selection to multiple faulty software entities in the automation process. The process required applicants to jump through multiple bureaucratic hoops, including dealing with automated family trees that often did not reconcile inconsistencies. The updated NRC in Assam that came out in August 2019 excluded a staggering 1.9 million people, rendering them stateless pending appeal. When the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party realised that several Bengali Hindus were amongst those excluded in the Assam NRC, they refused to respect it, called it error-prone, and asked for a Supreme Court review and an improved update.

The historical and ethnographic record clearly shows that even the most suitable and perfectly documented amongst us can speedily be converted into a mere ordinary resident of India.

The SIR in Bihar is being described as an exercise that brings in the NRC by the back door. While the parallels—especially this question of who is a citizen and who isn’t—are evident here, we would like to point to the resonances and the disparities. Staying attentive to electoral processes of roll revision shows us a related but different approach to the question of who can vote, rather than who can live, in New India. However, as Assam’s NRC (evidenced by the “doubtful” or “D” voter status applying to voters in Assam who could not prove their citizenship) and the current SIR have shown us, a non-voter is also highly likely to be counted as a non-citizen. What is clear with both is that documents and IDs have assumed monstrous powers over marginalised lives, and that the state is clearly going further and further down the path of sorting out who can and cannot belong in New India.

What makes it further impossible to gauge how new processes of identification of the voter or the citizen will go is that there is a terrifying temporality to them. Documentary, spectral, and non-documentary modes of identification can shift swiftly in line with political expediency. For instance, in the case of Bihar’s voters, the upcoming elections can come to suddenly matter with a particular urgency.

Finally, a word of caution. If we think we are going to remain exempt from this impossible task of proving extraordinary citizenship of India, we need to think again. As the NRC exercise in Assam showed in its early iteration, a range of figures—including those who were able to submit all the requisite documents but had a single member in the family whose name didn’t match across documents—can be swallowed up by databases, algorithms and data operators and spat out as inadequate. The SIR, too, is proving to be an impossible task for many. The historical and ethnographic record clearly shows that even the most suitable and perfectly documented amongst us can speedily be converted into a mere ordinary resident of India.

Nayanika Mathur is the author of Paper Tiger: Law, Bureaucracy and the Developmental State in Himalayan India (Cambridge University Press, 2016). Tarangini Sriraman is the author of In Pursuit of Proof: A History of Identification Documents in India (Oxford University Press, 2018).