More than half of the rural households of Jharkhand depend on manual casual labour as their main source of livelihood. In times of distress, an even larger number of households take up casual labour. In the dearth of adequate and assured local employment, a large proportion of the working-age population migrates to the towns and cities in the state and to other states.

The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) also knowns as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) is a lifeline for many workers in Jharkhand because they are able to get some employment under the programme. NREGA was the only significant source of rural work during a large part of the pandemic.

The importance of NREGA in addressing rural distress and poverty has been extensively studied and documented (e.g., Desai et al. 2015, Bhaskar et al. 2016, Narayanan 2020). Since NREGA began in 2006, several important community and individual assets have been created under the programme in Jharkhand, such as rural roads, irrigation wells, ponds and mango orchards.

Successive state governments in Jharkhand have … failed to utilise the immense potential of NREGA in providing assured wage employment and creating productive assets.

However, the commitment of the union government to NREGA has been on the decline for more than a decade. The downslide started under the United Progressive Alliance-2 (UPA-2) government and has worsened under the Narendra Modi-led government. Barring the pandemic years, NREGA has been grossly underfunded under the Modi government. Successive state governments in Jharkhand have also failed to utilise the immense potential of NREGA in providing wage employment and creating productive assets. Lack of timely and adequate employment, delays in wage payments and corruption have plagued the programme in the state since its inception.

The union government’s apathy in the last decade and continuing patchy implementation by the state have made Jharkhand’s workers sceptical about the benefits of NREGA. It is not uncommon to see workers across the state stay away from NREGA as, “Na kaam milta hai aur na samay par paisa” (Neither do we get work nor timely wages).

Underfunding

Contrary to the spirit of the NREGA Act, continuous underfunding by the union government has diluted the demand driven nature of the programme, i.e. workers cannot get assured employment on demand. Nationally, since 2015-16, almost every year has begun with significant arrears in wage payments. In the last five years, about a fifth of the annual budget has been used just to clear the arrears across the country.

In Jharkhand, the underfunding reflects in the poor scale of work in Jharkhand. Since 2014-15, only about 30 per cent of the total registered rural households have got work in a year, and that too only for an average of just 40-45 days[1].

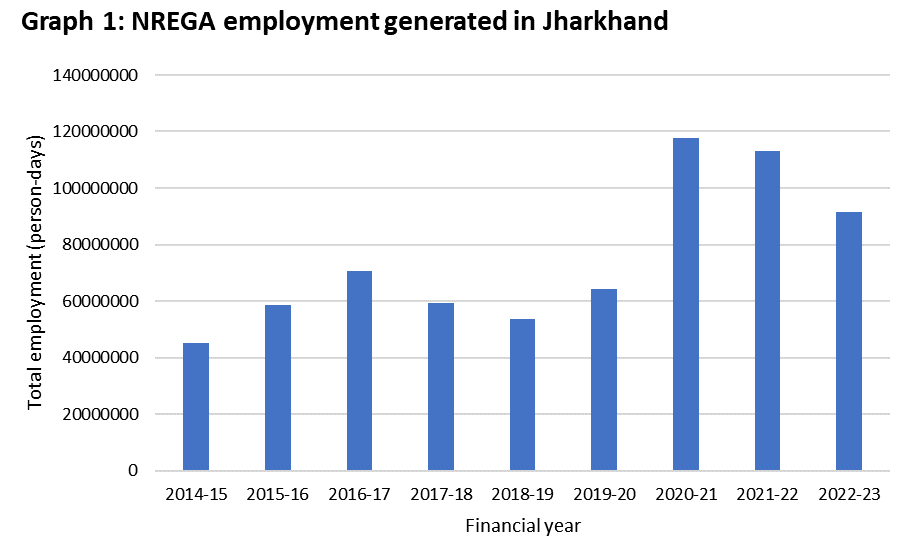

The rural distress caused by the ill-conceived lockdown and then the pressure by groups advocating for the rights of NREGA workers forced the union government during the pandemic to increase the NREGA budget for 2020-21 by 40%. This almost doubled the scale of work in Jharkhand compared to the previous five years (see Graph 1). The total number of households that got at least some work also doubled as compared to the previous year.

According to field evidence and local news reports, wages payments had stopped in the state in July-August this year and there has also been a delay in the release of funds by the centre…

However, the union government’s focus on NREGA during the pandemic was short-lived. The national allocation was curtailed after 2020-21. As a result, the total employment in Jharkhand dipped in 2021-23.

In the current financial year, the national NREGA budget of Rs 60,000 crores is a third less than last year’s allocation. It is the lowest allocation ever for the programme, when measured as a proportion of the country’s Gross Domestic Product. It is no surprise that almost 95% of the total budget for the current financial year was spent by September. As a result, wages of Jharkhand’s workers have stopped being paid in the middle of 2023-24, as the ministry’s NREGA data shows . The wage pendency is 100 per cent. According to field evidence and local news reports, wages payments had stopped in the state in July-August this year and there has also been a delay in the release of funds by the centre. (See here, here and here for reports in local media about non-payment of wages in Jharkhand.

According to news reports, the Rural Development Ministry has requested an additional allocation of Rs. 23,000 crore for the NREGA programme across the country for this financial year. However, it takes months for the additional funds to be allocated and until the additional funds are sanctioned, wage payments stop and frontline functionaries are discouraged from providing employment under the programme.

The NREGA funds and wage payment process were centralised in 2016. Now, once the fund transfer orders (FTOs) are electronically approved by the local administration, the wages, based on the FTOs, are to be credited by the union government. to the workers’ account from the central NREGA account. Between 2019-20 and 2022-23 (data of earlier years is not available), barely half of total wage transactions for Jharkhand were approved on time by the union government. The delay increases in the last quarter of each financial year when the shortage of funds becomes most acute. Ground reports suggest that a large proportion of wage transactions remain pending for several weeks. The exact proportion and extent of delay are difficult to assess as the union government, going against the spirit and mandate of the act, does not make this information public.

The centralisation has also made it difficult for the states to redress payment grievances. Jharkhand, unlike in the pre-centralisation years, is now unable to utilise its own revolving fund to tide over delays in release of funds by the union government.

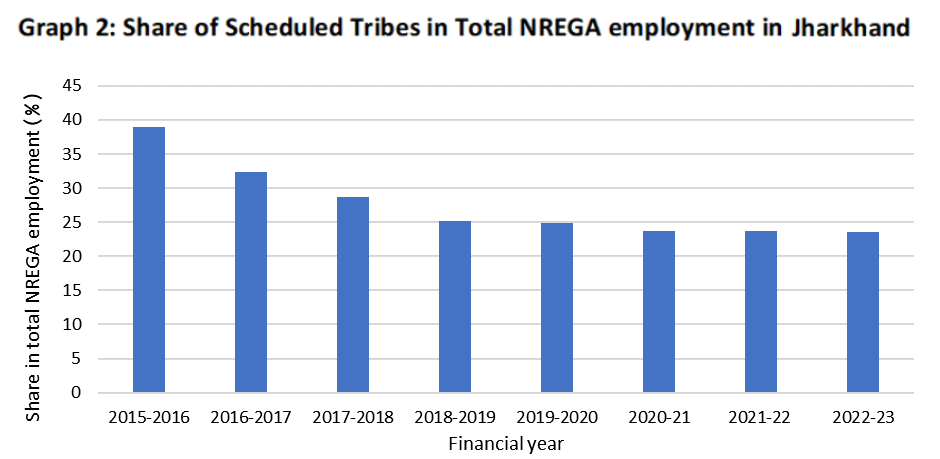

The uncertainties in getting adequate work and timely wages has led to a reduction in the proportion of the total NREGA employment accessed by the Scheduled Tribes, who constitute 27 per cent of the state’s total population.

For over a decade now, NREGA workers across the country, including in Jharkhand, have been suffering from the stagnation of the wage rate that is determined by the union government. Jharkhand’s current NREGA daily wage rate of Rs 228 is a third less than the state’s minimum wage. This is a significant disincentive for workers to seek NREGA work. Since 2021, the Jharkhand government has been adding Rs 27 to the wage rate from its own funds, but the wage rate is still considerably less than the state’s minimum wage.

The uncertainties in getting adequate work and timely wages has led to a reduction in the proportion of the total NREGA employment accessed by the Scheduled Tribes (STs), who constitute 27 per cent of the state’s total population. This proportion has come down from 39 per cent in 2015-16 to 23.5 per cent in 2022-23 (Graph 2). Ground evidence suggests that a number of other factors may also be responsible for the shrinking share of ST employment.

The sharp increase in the share of NREGA works on private lands (as compared to community lands) since 2016-17 may also be responsible for this fall in employment. The proportion of schemes on private lands, as compared to those on community lands, almost doubled from 38 per cent in 2015-16 to 72 per cent next year (because of the union and state governments’ focus on increasing individual schemes). Since then, almost 80 per cent of all ongoing schemes every year comprise individual works. There is anecdotal evidence of greater access by non-Adivasi households to individual schemes than by Adivasi households. The change in Jharkhand in the demographic composition of the total registered job cards (cards in manual and electronic forms issued to households registered in the programme) also indicates this. The proportion of job cards by members of ST households in the total registered households fell from 38 per cent in 2015-16 to 28 per cent in 2022-23. Ground evidence also indicates an increase in corruption by registering fake attendance of non-Adivasi households.

Use of unsuitable technologies

The wage payment system has become excessively digitised and complicated over the years. It has undermined workers’ ability to get timely work and wages in Jharkhand. The most recent examples are the National Mobile Monitoring System (NMMS) and the Aadhaar payment bridge system (APBS).

The union government made NMMS-based attendance mandatory from January 2023. Geotagged and time-stamped photographs of workers and online attendance are to be taken twice a day at the worksite through a phone-based app. The stated objective of NMMS is to check for fake attendance. This is based on an absurd premise that local officials will verify photographs of hundreds of workers taken at worksites with the attendance on muster rolls and the photographs on their job cards or through physical inspection of worksites.

While the NMMS fails in its stated objective of checking fake attendance, it has become another hurdle faced by Jharkhand’s workers in getting timely work and wages. Lack of access to smart phones by the worksite supervisors, especially of women supervisors, is a hindrance. Even after finishing their work, workers have to be present at the worksite until their photograph is taken. Poor internet connectivity and other technical glitches directly affect the capture of attendance. There are several reports of workers losing their wages after the local administration marked them as absent because of technical issues with the NMMS app.

Another roadblock for Jharkhand’s workers is the Aadhaar-based Payment System (ABPS). Under the APBS, a worker’s wages are to be credited to the bank account that was last linked with their Aadhaar (in non-APBS payments, the wages are sent directly to the bank account of the worker). For the APBS to work, the Aadhaar of the worker must be correctly seeded with their job card and their functional bank account and the Aadhaar, and account details are to be electronically mapped by the respective bank at the National Payment Corporation of India (through which the payment transaction is done). The rural development ministry claims that the APBS leads to faster payments and reduction in corruption.

There are several reports of workers losing their wages after the local administration marked them as absent because of technical issues with the NMMS app.

There is widespread evidence that the delays and uncertainty in receiving timely wages increased in Jharkhand after the introduction of the APBS. Transfer of wages of workers to incorrect bank accounts mapped with their Aadhaar without their knowledge is common. Another persistent issue is of wage payment getting rejected due to technical reasons, i.e. money is not credited to the worker’s account even though it was transferred by the union government. Workers have to run pillar to post to understand where their payment is stuck. Frontline functionaries are often themselves clueless about it and are unable to rectify the issue.

Contrary to the claims of the ministry, a recent study by Libtech India of 3.13 crore wage transactions in 2021-22 across 10 states, including Jharkhand, shows that there is no significant difference in the time taken to processes payments between the APBS and non-APBS systems. Despite the evidence of no gain in the APBS, the union government made it mandatory for wage payments from February 2023. Since then, protests by workers and peoples’ organisations have forced the ministry to repeatedly extend the deadline for making the APBS mandatory.

However, in practice, the APBS is mandatory in Jharkhand. The frontline functionaries are under pressure from the administration to convert all registered households to APBS. As a result, many workers who are not APBS-enabled are not being given work, to meet the target of making all workers APBS enabled. In addition to this, the ministry has tweaked the NREGA implementation software to make sure that the wages of a set of workers on a muster roll cannot be processed anymore if there is even one worker among them who is not APBS-enabled. In West Singhbhum district, several workers were marked absent though they had completed the project work, only because some of them were not APBS-enabled.

The pressure from the ministry for bringing workers on to the APBS wage system has also led to large-scale deletion of job cards across the country, including Jharkhand, because they have not been enabled for APBS (see Buddha and Tamang 2023). According to the reply to a question in the Lok Sabha (Starred Question 61 of 25 July 2023), the names of 24 lakh workers were stuck off the list in Jharkhand in the two years 2021-22 and 2022-23. Ground evidence suggests that many of these workers exist and are not fake. Women, especially, are facing the brunt of the APBS as their names are not always changed after marriage in both their Aadhaar and job cards, resulting in different names on both the documents. As a result, they cannot be easily made APBS-enabled and are being denied work or being stuck off the list. In the last decade, whenever there was pressure from the rural development ministry for linking Aadhaar of NREGA workers with their job cards and bank accounts, job cards of many of Jharkhand’s workers, not linked with Aadhaar, were deleted to meet the target.

Worker groups in Jharkhand have repeatedly protested against the imposition of NMMS and APBS and deletion of job cards. Gram Panchayat Mukhiyas have also written to the Union Minister for Rural Development demanding repeal of these technologies. The state bureaucracy, instead of acknowledging these issues and advocating for their redressal, continues to toe the central government’s line.

Corruption

As mentioned earlier, corruption in the implementation of NREGA is a major issue in Jharkhand. An audit of ongoing schemes by the state’s social audit unit in October 2021 found only 25 per cent of the total workers registered in the muster roll present at the worksite. A nexus of contractors, frontline functionaries and, at times, the local elected representatives is usually involved in siphoning off funds. It is becoming increasingly common for this nexus to get muster rolls issued in the names of people who do not work and then give them a weekly cut to withdraw the wages from their bank accounts. While some schemes just exist on paper, in many schemes a part of the required work is usually done by a few workers who are paid in cash and the rest of the money is siphoned off. In clear violation of the act, the use of excavation machines (while showing employment in the name of workers) is also not uncommon.

NREGA includes mechanisms for ensuring accountability and checking corruption such as the use of independent social audits, a grievance redressal system and independent ombudspersons. But implementation remains poor in Jharkhand. The violations and irregularities found in the audits are usually not effectively redressed, with financial recoveries and punitive action against erring functionaries. In fact, the current state government stopped the audits in 2020 right after taking office, citing irregularities in their conduct. There were reports that the corruption nexus and even some MLAs close to the ruling parties put pressure on the government to take this decision. It was begun again only a year later, after being flagged repeatedly by worker organisations and even the union government for violating the NREGA act.

Conclusions

NREGA is dying a forced death in Jharkhand as workers are growing disenchanted with the programme. The word guarantee in the act has lost its meaning for the workers. Their disinterest has made it easier for the corruption nexus to siphon off funds. The state government needs to establish an effective grievance redressal mechanism, address implementation lacunae such as large-scale vacancies of frontline functionaries, and check violations of workers’ entitlements like non-payment of unemployment allowance and the non-existence of worksite amenities, and so on. There is an urgent need for the union government to provide adequate funds, increase the wage rate and remove the ill-suited technologies from the programme and ensure timely payment of wages. Collectives of workers from Jharkhand and other states have repeatedly raised these issues before the union government. However, the government’s apathy towards NREGA workers in the past decade leaves little room for any hope.

Siraj Dutta is an activist based in Jharkhand.