The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), a welfare scheme launched on 28 August 2014 as the biggest financial inclusion initiative in the world, created a Guinness Book of World Records record for the most bank accounts opened in a week—between 23 and 29 August 2014. Implemented on a mission mode with the existing financial infrastructure, a glance at its website reveals impressive numbers—around 560 million beneficiaries with a total balance of Rs. 2,640 million in their accounts at the end of 11 years. Indeed, worth applauding, but does it complete the story of financial inclusion?

Perhaps not. Comprehensive financial inclusion requires more than just owning a bank account. So why are these numbers being highlighted? What steps were actually taken to address the massive expected increase in demand for financial services? And to what extent is it justifiable to make welfare schemes so heavily dependent on banks? The implementation and management of this scheme raise several such questions.

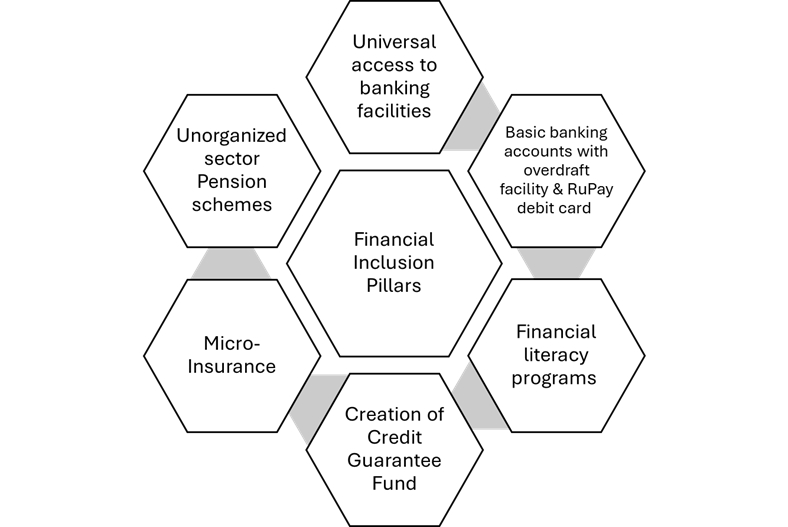

Importantly, our scepticism is rooted in the scheme’s own policy document, which defines financial inclusion in a broader sense—beyond the headline numbers included in the six pillars portrayed in Figure 1.

The first three pillars were intended to be the focus in the scheme’s initial year. Then, in 2015, the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY) and Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (PMSBY), two insurance schemes, along with the Atal Pension Yojana, were launched under the Jan Dhan Se Jan Suraksha programme to address the additional pillars of insurance and pension. However, there is little detail about the rollout of the credit guarantee fund, which is the fourth pillar.

Figure 1: Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana: Pillars of Financial Inclusion

When it comes to the number of account holders and total deposits, there has been limited attention given to financial literacy, credit creation through overdraft facilities backed by the credit guarantee fund, handling of insurance claims under the two schemes, and the reach of the pension programme. Although the website and press releases mention these pillars, the information is either not clearly visible or only partially covered.

This selective representation of information can be misleading. Is there an attempt to mask the harsher realities of a lack of financial inclusion behind these numbers? An investigation to read between the lines thus becomes inevitable. We have to examine each of the pillars to understand what has been gained so far.

1. Universal Access

With the mission targeting a rapid increase in new accounts, especially in rural areas, building an adequate infrastructure of financial service providers became essential. Instead of establishing new providers, however, the approach taken was to expand existing bank branches using sub service areas (SSAs) and “bank mitras” (business correspondents, BCs), justified as a cost-saving measure. But given the speed at which accounts were being opened, could this expansion alone provide reliable support to the newly added, often vulnerable, customers? Quite unlikely.

BCs have been asking for fair pay so they can continue to deliver essential banking services. Given their key role, this demand cannot be ignored.

Further, shifting the main responsibility to banks—which typically operate on a profit-driven model and are not funded by the government—overlooked their existing methods and already high workloads. As of August 2025, only 3% of Jan Dhan accounts were with private sector banks.

The business correspondent (BC) model, introduced by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 2010, has been crucial for expanding the reach of the scheme. However, there are ongoing issues with both the number of BCs and their compensation structure.

First, the latest available infrastructure data is only up to 2017. At that time, 0.11 million BCs were working, compared to a required 0.13 million. The reported jump from 0.11 million in 2017 to 1.36 million in 2025 seems hard to believe. Further, BCs’ compensation combines a fixed component and a commission-based component. As account numbers have reached saturation, commissions have dropped, leading to steadily declining incomes for BCs.

BCs have been asking for fair pay so they can continue to deliver essential banking services. Given their key role, this demand cannot be ignored. If action is not taken, the BC model risks becoming unsustainable. A drop in BC interest would have serious consequences for the broader goal of financial inclusion.

2. Basic Banking Accounts

Zero-balance accounts—which serve as a first step toward financial inclusion—have existed since 2005, originating from the RBI’s no-frills account initiative, well before the launch of the PMJDY. The PMJDY built on this by providing RuPay cards with built-in accidental insurance, and an overdraft (OD) facility. However, apart from the widespread opening of accounts, progress in these additional areas has been limited.

Clearly, the scheme has made little difference in freeing beneficiaries from exploitative moneylenders. As a matter of fact, the situation appears to have worsened since its rollout.

For example, nearly 200 million accounts are still waiting for their RuPay cards, with only 387 million cards issued. Insurance claims are another major concern—with only 11,024 claims filed against 309 million RuPay cards, based on the latest available data from 2021. As for the OD facility, the requirement of six months of satisfactory financial performance is misaligned with the welfare intent of zero-balance accounts. It is clear that maintaining a regular balance in these accounts is a genuine challenge.

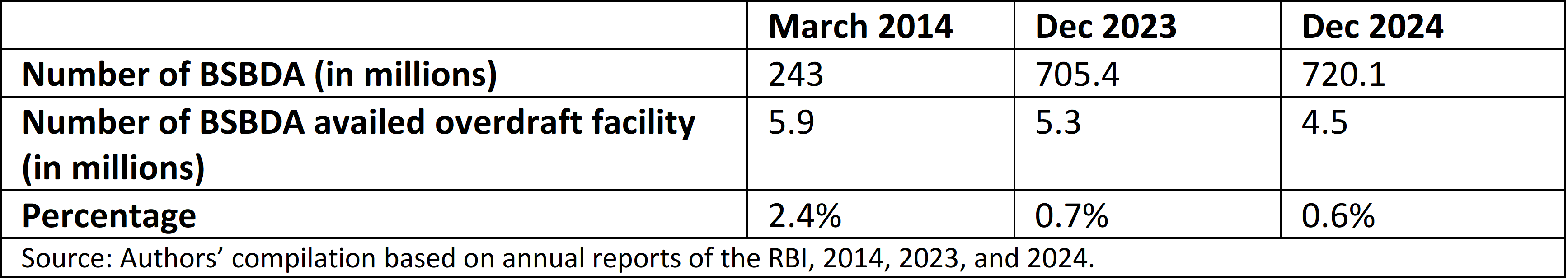

This perhaps explains the decline in the percentage of basic savings bank deposit accounts (BSBDA) availing themselves of the OD facility. Out of 700 million BSBDA accounts—mostly PMJDY accounts—only 5.3 million (0.7%) made use of the facility by December 2023. This figure dropped further to 4.5 million out of 720 million (0.6%) in provisional 2024 data.

Table 1: Availed Overdraft Facility in Basic Savings Bank Deposit Accounts, 2014, 2023, and 2024

Interestingly, before the PMJDY was launched, a much higher percentage (2.4%) of BSBDA holders availed themselves of OD. Clearly, the scheme has made little difference in freeing beneficiaries from exploitative moneylenders. As a matter of fact, the situation appears to have worsened since its rollout.

3. Financial Literacy

Policymakers clearly recognised the importance of financial literacy, both in general and for the scheme’s target population. The policy document itself provides a detailed justification for expanding the RBI’s financial literacy and counselling centres. However, when assessing the actual efforts made, the official website offers very limited information.

It is difficult to find any specific initiatives focused on improving financial literacy for account holders. The available details are mostly limited to the activities of various banks, and even these are not up to date. The website does mention some programmes and tutorials run by the RBI, and provides a link to the National Centre for Financial Education. But can these measures alone be sufficient to tackle the widespread need for financial literacy? Just as banking was brought to people’s doorsteps—causing a dramatic increase in account ownership—should we not see similar large-scale initiatives aimed at promoting financial literacy?

4. Credit Guarantee Fund

To help people escape the grip of moneylenders in both rural and urban settings, the policy document proposed a credit guarantee fund with a corpus of Rs. 1,000 crore. However, this fund was designed to be budget-neutral for the government of India. Instead of being managed within the scheme itself, responsibility for its implementation and operation was assigned to the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD).

It is hard to determine how effective these decisions were for credit creation. When we tried to assess progress or understand how this fund has been used, we could not find any relevant information—neither on the PMJDY website nor from NABARD. Is the fund’s existence only on paper? This helps explain why overdraft facilities are being used so minimally.

5. Micro-Insurance

The situation is even more troubling with the linked insurance schemes, which require a bank account but not necessarily an account under the PMJDY. First, the approach of selling—rather than freely providing—insurance products to vulnerable populations is at odds with the spirit of welfare. This scheme has not just one but two such insurance components. The Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana is a term life insurance plan, and the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana is an accidental insurance cover. Both require the payment of premiums but offer no maturity or surrender benefits.

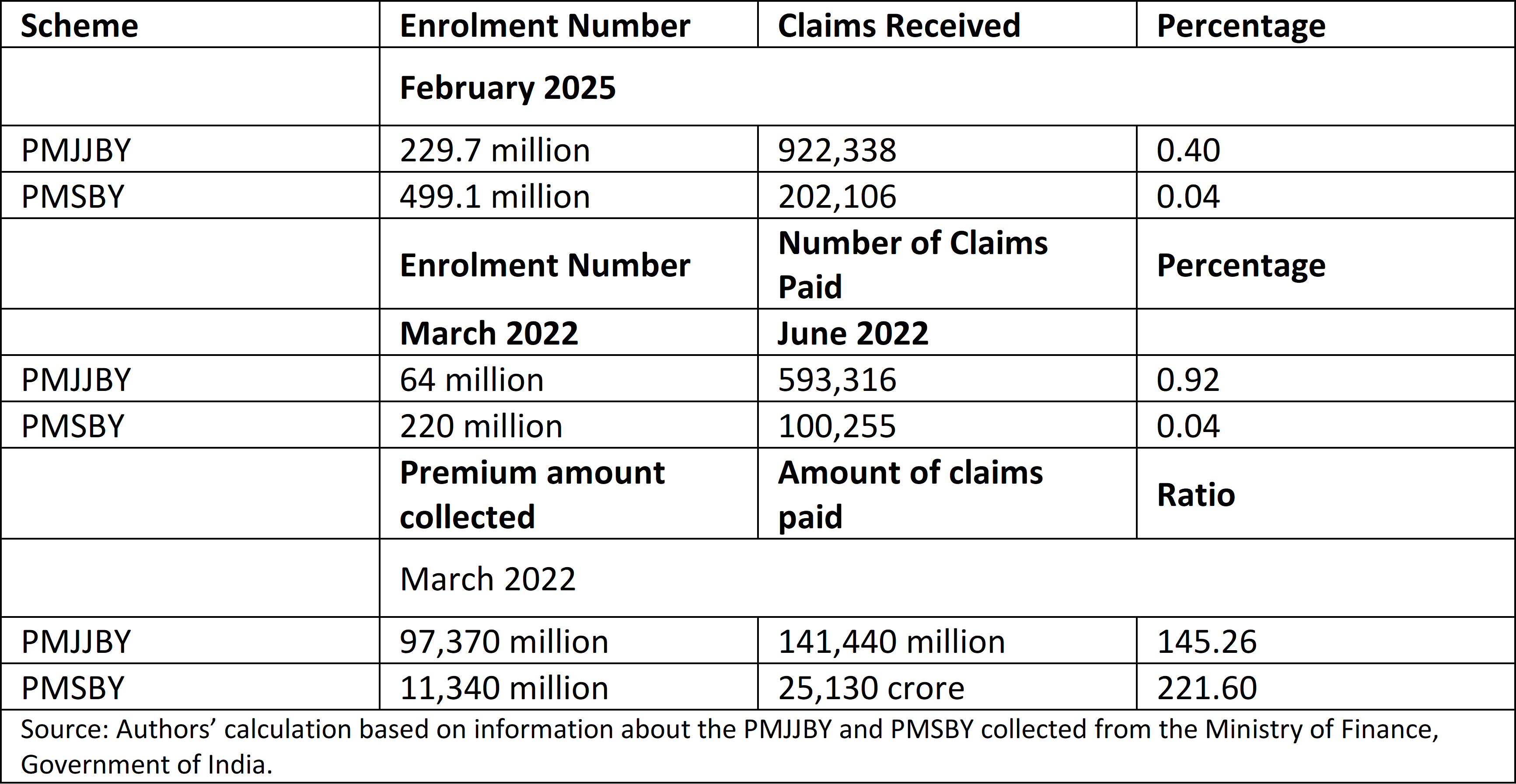

At first glance, these schemes appeared to gain massive acceptance. Enrolment figures were 230 million for the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana and 499 million for the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana as of February 2025. However, to understand the full picture, insurance claims must be analysed. The available data evaluates claims using two indicators:

Claim percentage = (Number of claims received or paid / enrolment numbers) × 100

Claim ratio = (Amount of claims paid / premium earned) × 100

As shown in Table 2, the claim percentage remains below 1% under both schemes, whether calculated in terms of number of claims paid (for 2022) or received (for 2025). While such tiny claim percentages should be of concern under the idea of jan suraksha (people’s protection), authorities have instead been worried about the claim ratios exceeding 100%, which means repeated losses for insurers. As a result, based on recommendations from the Insurance Regulatory Development Authority of India (IRDA), the premium rates were increased—effective 1 June 2022—to Rs. 20 from Rs. 12 for the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana and Rs. 436 from Rs. 330 for the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana.

Insurance should not be about just increasing enrolment numbers, especially when the vulnerable population may not be seeking or receiving the protection these schemes promise.

While premium rates were revised seven years after the schemes were introduced, it is worrying that this action became necessary despite such low claim percentages. Insurance should not be about just increasing enrolment numbers, especially when the vulnerable population may not be seeking or receiving the protection these schemes promise. When such schemes target the weaker sections of society, it is worth questioning whether it is reasonable to depend so heavily on premium collections for payouts in the first place, or how prepared insurance companies really are to pay claims if the claim rate rises even modestly above 1%.

Table 2: Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana and Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana: Percentage of Claims Received, 2022 and 2025

More fundamentally, the way insurance companies operate raises questions. How can these companies sustain participation in a welfare-oriented scheme without additional support or proper arrangements? When so many other aspects of financial inclusion remain underdeveloped, these insurance schemes seem less relevant—especially when RuPay cards already come with built-in accidental insurance. This situation affects both buyers who cannot really afford premiums and insurers who face losses with so few claims.

6. Unorganised Sector Pension Schemes

Despite acknowledging the importance of providing income security in old age, the policy document did not expand existing provisions. Instead, it simply referred to the already existing Swalamban scheme, which was launched in 2010. Under the PMJDY, this scheme was renamed as the Atal Pension Yojana in 2015. The Atal Pension Yojana is a contributory, government-backed pension plan aimed at encouraging savings for a secure old age. Unlike other pillars of the scheme, it has no prerequisites for joining, yet its reach remains very limited.

This limited form of financial inclusion falls short of what was envisioned in the policy document, which is why its reported success stories are few and far between.

While insurance schemes that do not offer assured returns have seen massive enrolment numbers, the Atal Pension Yojana, by contrast, had only 76.5 million subscribers as of April 2025—and this figure is not exclusive to PMJDY account holders. If we assume, for a moment, that the requirement of regular contributions hampers its uptake, what then explains the skyrocketing enrolment in insurance schemes that also require premium payments? Could lack of awareness be part of the answer? In any case, this significant discrepancy needs to be understood if welfare remains the central goal.

These facts raise serious questions about the welfare benefits actually delivered by the PMJDY. While the scheme has expanded bank account ownership, these accounts are being used mainly to purchase insurance policies—not to access institutional credit, secure old age income, or make insurance claims. This limited form of financial inclusion falls short of what was envisioned in the policy document, which is why its reported success stories are few and far between.

The real gaps emerge not from the concept but from the way the scheme is implemented, with banks and the insurance sector serving as the primary executors. These industries are not ideally positioned to run welfare schemes, especially without adequate support to maintain their viability—let alone profitability.

Moreover, the scheme has neglected supply-side measures that could improve financial inclusion behaviour, such as promoting financial literacy, ensuring RuPay cards reach all account holders, or deepening access to credit. Large numbers of zero-balance accounts have further loaded banks with increased operational costs. In the drive to stay competitive and cut costs, banks may have deferred efforts to provide financial literacy and information about the scheme’s full range of benefits—effectively limiting demand for broader financial services.

The insurance industry, another central player in the scheme, has dealt with its own survival by shifting the burden onto already vulnerable account holders through repeated increases in premium rates. Meanwhile, expecting overburdened banks to closely track and analyse claim settlement trends is simply unrealistic. As a result, insurance under this scheme operates as a numbers game—enrolment keeps rising, but genuine benefits rarely reach most policyholders due to a lack of information and outreach.

It is fair to say that the scheme’s implementation has focused heavily on increasing account numbers and insurance enrolments, while other crucial pillars have been largely overlooked.

For the general public, the scheme is often seen as a means to receive direct government transfers. While some people did benefit—particularly women account holders during the pandemic under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana—such payments were limited and temporary. The scheme has certainly empowered weaker sections, but by bringing them into the formal system without adequate financial literacy, it has also left them more exposed to financial fraud and related risks.

It is hard to believe policymakers did not anticipate these outcomes when entrusting implementation to banks and insurance companies without the necessary structural and budgetary support. In essence, the goal of boosting financial inclusion through greater access to credit, insurance, and pension remains largely symbolic. It is fair to say that the scheme’s implementation has focused heavily on increasing account numbers and insurance enrolments, while other crucial pillars have been largely overlooked—a pattern reflected in the selective reporting of its achievements.

Numerous concerns about the scheme have continued to be raised by key institutions such as the RBI and the IRDA, as well as by independent researchers.

Even the IRDA raised concerns as early as 2015 about how the insurance products attached to these accounts were being used, as documented in their journal, and these points were reiterated in 2024 from the perspective of “building the relevant micro-insurance product”. Scholars Sinha and Azad (2018) also questioned the nature of financial inclusion under the PMJDY, raising issues that are still highly relevant—and, indeed, even more pressing—in 2025.

Undoubtedly, the PMJDY has achieved something remarkable by including a large segment of the population, especially women, within the formal banking structure, thereby creating new opportunities. It has also helped establish the infrastructure necessary for direct benefit transfer of government welfare schemes. However, it still falls short of fostering independent financial participation.

Now, the PMJDY urgently requires major reforms to deliver financial inclusion in a real and meaningful sense—not just in terms of numbers, but in spirit as well. This can be achieved particularly by actively involving non-profit institutions such as post offices and by building robust financial literacy initiatives. The shift in focus from “every household” to “every adult” might have been premature. At this stage, it is vital to prioritise genuine inclusivity over record-breaking account numbers.

Kshipra Jain is with the Department of Economics, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, and is the author of 'Financial Literacy and Ageing in Developing Economies: An Indian Experience' (Routledge, 2023). Manish Sinsinwar is with the Department of Philosophy, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, and has been Associate Editor of the Journal of Foundational Research.