In an act of unprecedented haste, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has granted clearance for a mega project to build an International Container Transhipment Port (ICTP) at Galathea Bay in Great Nicobar Island. The Detailed Project Report (DPR), prepared by Kamarajar Port Ltd. (KPL), is complete.

The proposed Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island has generated significant opposition from a broad coalition of scientists, environmentalists, and social experts...

However, at the time of writing, it has not yet been submitted to the Union Shipping Ministry for the necessary final approval. The project will only proceed to the tender stage, where private players can participate, once this ministerial approval is secured. The port is planned in phases, over decades, finally acquiring a maximum handling capacity of more than 16 million TEUs annually.

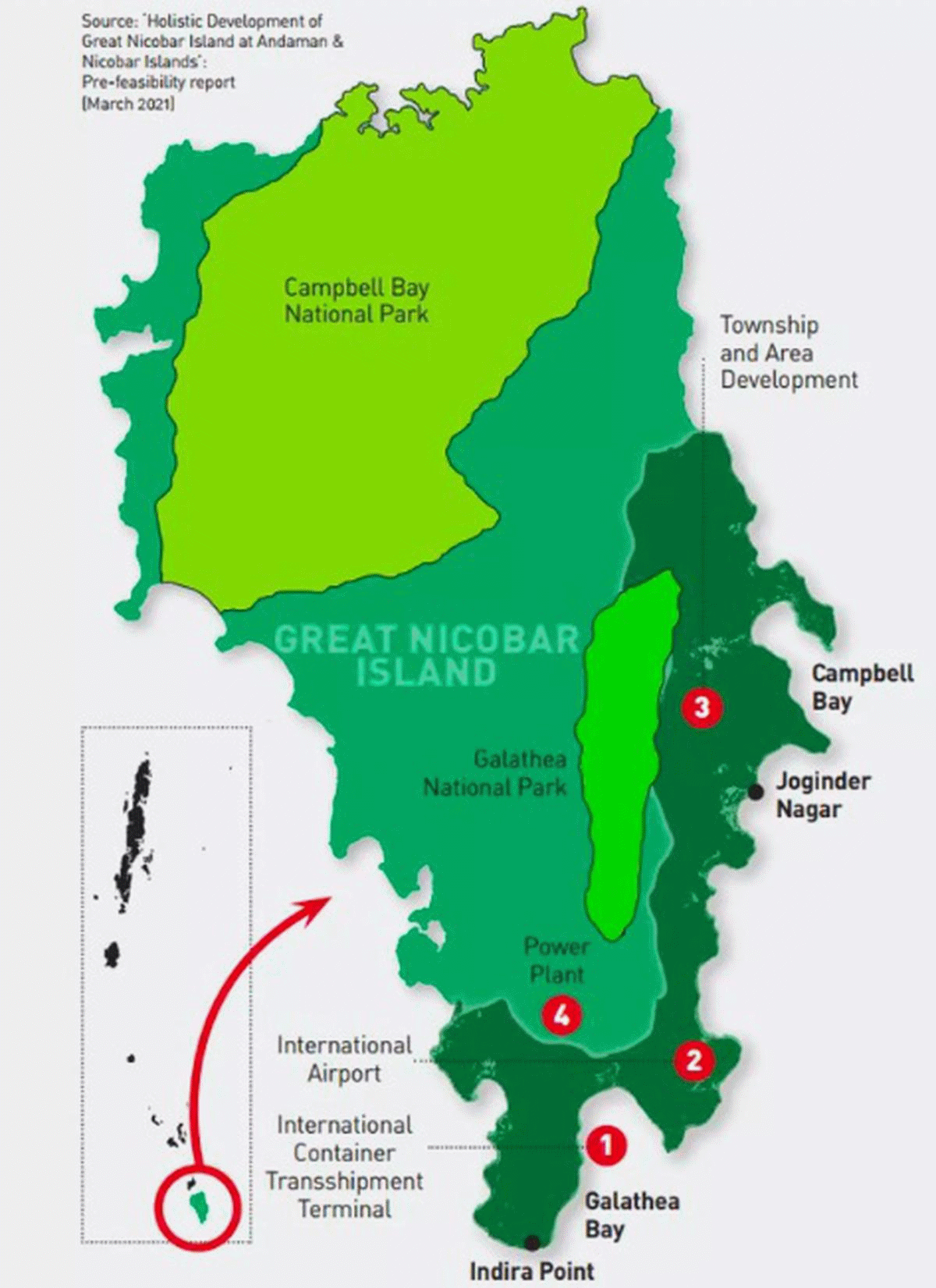

Euphemistically titled the “Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island”, the mega project spearheaded by NITI Aayog entails severe and irreversible environmental consequences. The plan involves constructing an international transhipment port at Galathea Bay, an international airport, a 450-MVA gas/solar power plant, and a 160-square kilometre township on this tectonically sensitive and ecologically unique island.

The promoters aim to develop an urban landscape that rivals Singapore’s and Hong Kong’s, utilising the island’s strategic location on the Malacca Strait. The proposed built environment, covering approximately 80% of the project area, is intended to include hospitals, shopping and entertainment centres, luxury tourism infrastructure, and residences for an estimated population of 350,000 people.

This scale of development represents a fundamental transformation to an urban landscape. The island’s current population of approximately 8,000 would increase by an unprecedented 4,000%. In essence, this is not merely a development project; it is a plan to convert a globally significant biosphere reserve—a haven of unique biodiversity—into a sprawling commercial and strategic hub, raising critical questions about the true meaning of “holistic” and “sustainable”.

The proposed Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island has generated significant opposition from a broad coalition of scientists, environmentalists, and social experts, who cite grave concerns over its potentially irreversible ecological, social, and geological impacts. This critical perspective has been extensively documented in leading media outlets such as The Hindu, Frontline, and The Wire, as well as in Pankaj Sekhsaria’s book, The Great Nicobar Betrayal (Frontline, 2024). These analyses argue that labelling the initiative as “holistic development” is a profound misnomer, contending that it will effectively convert a vital tropical forest into an urban concrete jungle.

The debate intensified most recently on 27 October 2025, when over 70 prominent experts issued an open letter directly responding to Union Minister Bhupender Yadav’s defence of the project. In their collective response, they urgently called on the Minister and the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change to prioritise a scientific assessment of the project’s grave and irreversible implications over political considerations.

Economic Rationale

The Indian government’s push for the Great Nicobar project is driven by a strategic ambition to recapture 75% of India’s transhipped cargo currently handled by foreign ports such as Colombo, Singapore, and Klang. The vision is to transform the island into a free-trade zone akin to Hong Kong or Singapore to attract multinational corporations.

Indonesia and India are jointly planning another transhipment port in Sabang, Indonesia, located just 190 km away, which could directly compete for the same maritime traffic and undermine Great Nicobar’s economic viability.

As Union Home Minister Amit Shah stated at the India Maritime Week 2025, the project is positioned as a major boost to India’s global trade, with a 30-year implementation timeline expected to draw nearly 400,000 people—a figure equivalent to the current population of the entire Andaman and Nicobar archipelago.

Great Nicobar is being drummed up as a deep draft and a strategically located port that could outpace its competitors. But this vision is fraught with logistical and economic contradictions that challenge its feasibility.

As pointed out by Retired Rear Admiral Kapil Gupta, many of India’s previous attempts to develop transhipment terminals (for instance, Vallarpadam in Kochi, Mundra in Gujarat, and Vizhinjam in Thiruvananthapuram) have not been a success in terms of their ability to attract sufficient traffic due to the draft limitations, limited hinterland connectivity, and competition from other international players. 1Seagull, Nov 2025–Jan 2026, pp. 30-33.

A critical, understated factor is that Great Nicobar is fundamentally unsuitable for a major transhipment hub. Unlike Singapore or Hong Kong, it is an isolated, thickly forested island located more than 1,000 km from the mainland with no supporting hinterland for cargo generation or consumption.

This internal contradiction is starkly evident in the project’s own documentation. A 2021 technical report by M/S AECOM India Limited paints an optimistic picture of a “greenfield city” with a diverse economy. Yet, a July 2016 technical note from the same consultant to the Ministry of Shipping concluded that a Free Trade Zone and transhipment hub “may not be a favourable option due to insufficient hinterland demand and supply”.

Furthermore, the project faces stiff external competition. Indonesia and India are jointly planning another transhipment port in Sabang, Indonesia, located just 190 km away, which could directly compete for the same maritime traffic and undermine Great Nicobar’s economic viability.

Ecological and Social Cost

The promoters of the Great Nicobar project systematically downplay the immense, irreversible cost of destroying natural assets and ecosystem services—a critical loss for a country already facing severe environmental degradation. India’s ambition to become a maritime leader comes at an incredible ecological price, threatening one of its most unique and protected landscapes.

Anthropologists and social experts unanimously argue that the project brazenly bypasses the Forest Rights Act and other legal safeguards, proceeding without the free, prior, and informed consent of the tribal communities...

The project area is part of a protected forest within the Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO-recognised site covering 85% of the island. This area provides a sanctuary for approximately 24% of all local species. The government’s plan to clear approximately one million trees from this tropical rainforest will devastate a critical ecosystem that regulates the regional monsoon cycle through evapotranspiration. The proposal for compensatory afforestation in Haryana and Madhya Pradesh is scientifically meaningless, as these areas cannot replicate the unique, evolved ecology of the Great Nicobar Islands.

The proposed port at Galathea Bay will directly devastate extensive coral reefs and marine habitats. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report suggests translocating these organisms, a method with unproven success. This proposal is especially alarming given that corals worldwide are at a tipping point due to ocean warming and bleaching; translocation would add further stress, likely resulting in widespread mortality.

The island’s forests host 650 species of angiosperms, ferns, gymnosperms, and bryophytes, many of which are endemic. Its unique fauna includes: 11 species of endemic mammals, 32 species of endemic birds and seven species of endemic reptiles. Critically, Galathea Bay is a vital nesting ground for the globally endangered Leatherback Turtle, whose habitat would be irrevocably lost.

The island is home to the indigenous Nicobari and Shompen communities, the latter classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) with a history spanning over 10,000 years. More than three-fourths of the 900-sq km island is designated as a tribal reserve under the Andaman and Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation (1956). Anthropologists and social experts unanimously argue that the project brazenly bypasses the Forest Rights Act and other legal safeguards, proceeding without the free, prior, and informed consent of the tribal communities, thereby threatening their very survival and cultural integrity.

This project represents not merely an ecological miscalculation but a profound ethical and legal failure.

Permanent Tectonic Strain

Unlike the stable geology of Singapore and Hong Kong, the Great Nicobar Island region is under permanent tectonic strain, rendering it highly vulnerable to seismic activity and constant land-level changes in an area that is also predicted to witness a climatically driven sea-level rise. This fundamental geological reality poses an existential threat to any large-scale, permanent infrastructure extending out onto the sea.

The proposed mega infrastructure, including the International Container Transhipment Port and the new township, would be located directly in one of the world’s most seismically active and climatically hazardous zones.

The island is located perilously close to Banda Aceh, Indonesia—the epicentre of the catastrophic 2004 magnitude 9.2–9.3 megathrust earthquake. In response to that event, the Great Nicobar region itself experienced a sudden coseismic subsidence of 3 to 4 metres. This is not an isolated event but part of an ongoing tectonic cycle.

The region undergoes a predictable yet hazardous cycle of strain build-up and release. GPS data show the land slowly uplifting over the years during the interseismic interval as tectonic strain accumulates. This built-up stress is released during major earthquakes (coseismal phase), causing the land to subside abruptly. 2Paul, J., and C. P. Rajendran. “Short-Term Pre-2004 Seismic Subsidence near South Andaman: Is This a Precursor Slow Slip Prior to a Megathrust Earthquake?” Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 248 (2015): 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2015.08.006

This cyclical movement of “slow uplift and sudden subsidence” along an active subduction zone inherently destabilises engineered structures along the coast over the long term, making the integrity of a port, airport, and city fundamentally untenable.

Scientific studies confirm that the megathrust fault abutting the Sumatra-Andaman plate boundary is segmented, with each segment capable of generating great earthquakes independently. The historical record reveals a pattern of major seismic events affecting the region, including: the 1861 Nias-Simeulue earthquake (M~8.5); the 1881 Nicobar Islands earthquake (M 7.9); the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake (M 9.2-9.3), and the 2007 Sumatra earthquake (M 8.4).

This history demonstrates not isolated incidents, but a recurring pattern of great earthquakes along various segments, confirming the high and continuous tectonic strain variability around Great Nicobar.

The proposed mega infrastructure, including the International Container Transhipment Port and the new township, would be located directly in one of the world’s most seismically active and climatically hazardous zones. The geological and climatic evidence clearly indicates that the region poses a significant and permanent threat to the safety of any building stock, cargo, and the project itself, challenging the very logic of its proposed location.

Rhetoric and Reality

While defending the Great Nicobar Island project before the National Green Tribunal (NGT) on 30 October 2025, the Union Government asserted it is “fully aware” of the project’s likely impact on biodiversity and has a mitigation plan. This legal submission, however, raises a more profound question: if the government is aware, why do the detailed and collective concerns of independent scientists, environmentalists, and social experts remain systematically unaddressed?

The experts’ letter to the minister describes it as “an exploitative commercial proposal with a dubious and unviable economic future, as well as destructive of rich and diverse ecosystems, [which] is unwarranted and irresponsible”.

The message the Union Environment Ministry is sending by issuing its order dated 30 October 2025—which waives, from the period of validity of an already granted environmental clearance, any time when a project is stalled due to litigation—is clear: the Ministry seeks to assist projects that are facing court cases. By removing the stalled period from the project’s environmental clearance validity, the government ensures that legal challenges do not shorten the approval’s effective duration, making it easier for controversial projects to proceed despite ongoing court battles.

This pattern of disregarding expert warnings is tragically familiar. The letter to the Union Minister of Environment, Forest and Climate Change rightly draws a parallel to the so-called developmental programmes in the Himalayan states, where projects like the strategic road-widening in the state of Uttarakhand—defended in court as essential for defence, much like the International Container Transhipment Port is now—were pushed through the courts, despite expert objections, leading to an unsustainable influx of pilgrim tourists, massive death tolls, and devastation from subsequent disasters.

The experts’ letter to the minister describes the Great Nicobar project with stark clarity, labelling it “an exploitative commercial proposal with a dubious and unviable economic future, as well as destructive of rich and diverse ecosystems, [which] is unwarranted and irresponsible”.

This reality stands in jarring contrast to the environmental commitments expressed by India’s leadership on the global stage. On 2 October 2018, while receiving the United Nations’ Champions of the Earth Award, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated, “Climate and calamity are directly related to culture; if climate is not the focus of culture, calamity cannot be prevented. When I say ‘sab ka saath’, I also include nature in it.”

Such statements rightly generate hope and outline a national commitment to a “green development model”. This makes the pursuit of the Great Nicobar project all the more paradoxical. Given our country’s professed dedication to sustainability, why do we end up executing such unrealistic projects that sound the death knell for an irreplaceable natural asset? The chasm between stated principle and concrete action has never been wider or more consequential.