Introduction

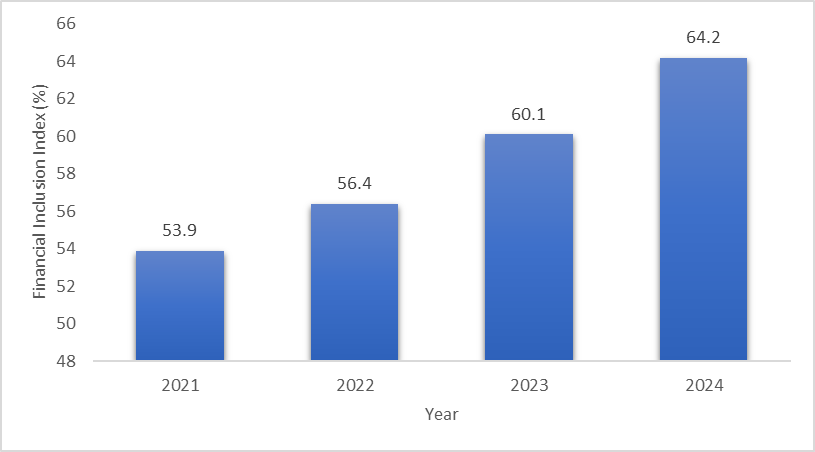

Conventional wisdom suggests that financial inclusion enhances economic growth and reduces poverty and income inequality (Demirgüç-Kunt and Klapper 2012). The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) introduced the Financial Inclusion Index (FI-Index) in August 2021—a combined measure based on access, usage, and quality—to track progress in financial inclusion.

The FI-Index value has steadily improved in recent years (Fig.1). These gains are mainly driven by improvements in the usage and quality of financial services, showing India’s substantial progress in broadening financial inclusion. However, much of the discussion around financial inclusion tends to focus on the adult population as a whole, with less emphasis on the gender gap. Of course, there are a few exceptions (Doss et al. 2020; Duvendack et al. 2023; Patwardhan 2018).

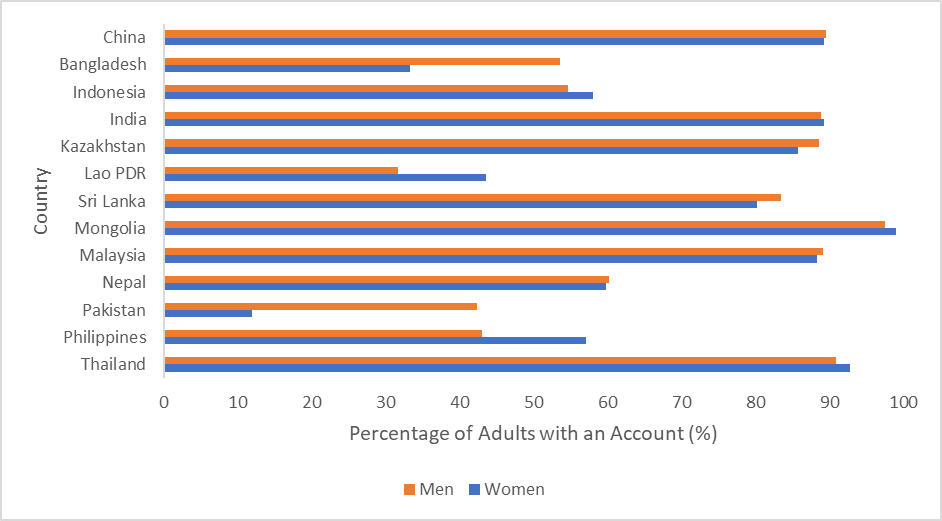

As per the Global Findex Database (2024) of the World Bank, women are less likely than men to have an account in financial institutions, especially in Asia and the Pacific regions (Fig.2). This gap is wider (about 20%) in countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan.

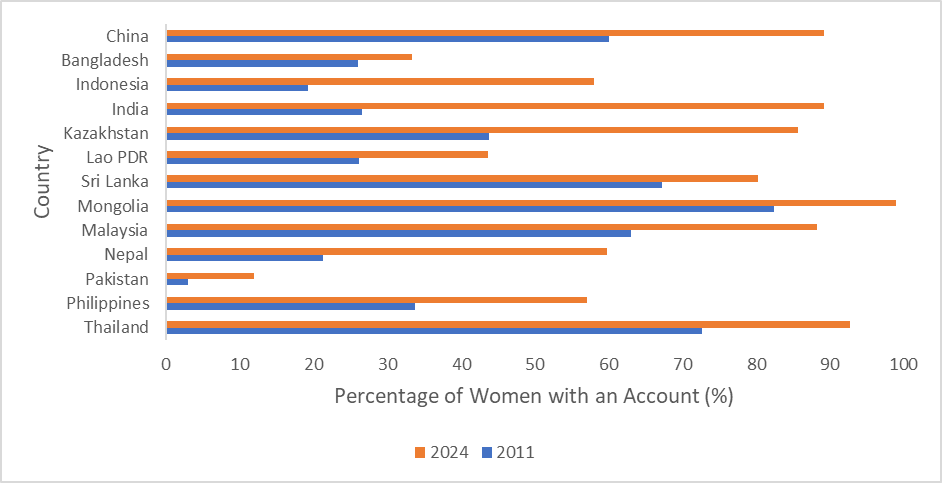

In India, the gap has largely closed. There has been significant progress in women holding accounts in the country since 2011, as shown in Fig. 3. Still, the frequency of account use remains a concern because many accounts are inactive. This raises the question of whether these formal accounts help build women’s ownership of financial assets.

Fig. 1: Trend in the Financial Inclusion Index

Former Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Niti Aayog, Amitabh Kant, said during the launch of a report titled “The Power of Jan Dhan: Making Finance Work for Women in India” that the “JAM trinity—Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, and mobile schemes—have financially empowered women to lead better lives and pursue their dreams of becoming entrepreneurs” (Economic Times, 18 August 2021). Does this conclusion follow from the data? Let us look at the key factors that are expected to close the gender gap.

Fig.2: Share of Men and Women Having an Account in Select Countries in Asia and the Pacific in 2024

Fig. 3: Percentage of Women Having an Account in Select Countries of Asia and the Pacific in 2011 and 2024

Closing the Gender Gap

Research shows that legal restrictions are crucial in explaining women’s exclusion from financial institutions. Women are significantly more likely to access bank accounts, save, and borrow in countries with stronger legal equality (Perrin and Hyland 2023), even after accounting for various individual and country factors. Conversely, where legal barriers inhibit women’s ability to work, manage a household, choose residence, or inherit property, they are less likely than men to engage in financial activities (Demirguc-Kunt et al 2013).

For example, as of 2022, married women in Equatorial Guinea required their husband’s consent to open a bank account. Other forms of discrimination, such as weak property rights or unequal inheritance laws, further restrict women’s financial agency. Women’s land ownership status affects their financial inclusion (Balasubramanian et al 2019). Thus, legal equality is supposed to reduce discrimination, improve women’s access to financial services, and shape both demand and supply-side behaviour in the sector.

Does the association between legal equality and financial inclusion, which has been observed elsewhere, hold in India, a country with formal legal rights for women?

High rates of teenage marriage and violence against women correlate with lower financial inclusion. Thus, while legal rights are necessary, social norms and enforcement determine whether legal equality translates into actual financial inclusion.

Women’s legal equality in India is formally protected in areas such as property inheritance, remuneration, and workplace safety, and there are no explicit legal barriers to access financial services. In spite of this, a gender gap persists in financial inclusion.

This suggests a divergence between formal legal provisions and actual experience, likely influenced by social barriers. Negative social perceptions based on entrenched norms can undermine women’s access as well as legal protection. When laws conflict with social customs, rule breaking is more frequent (Acemoglu and Jackson 2017), and legal reforms alone may be ineffective or even counterproductive (Bénabou and Tirole 2011).

For instance, high rates of teenage marriage and violence against women correlate with lower financial inclusion (Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2013). Thus, while legal rights are necessary, social norms and enforcement determine whether legal equality translates into actual financial inclusion.

We further argue that having an account is necessary to build savings, but not sufficient. Several factors influence saving with an account, including the ability to save, individual and household characteristics, and the efficiency of the banking system.

The literature suggests that women’s ownership of assets, rather than other household members’, significantly impacts their ability to save (Doss et al. 2020). Assets increase women’s agency and bargaining power, helping them save more. Asset ownership by women not only boosts their decision-making power and personal welfare but also benefits household well-being in many ways (Swaminathan et al. 2011).

The main criterion to be recognised for a woman to be a saver in the formal sector is that she must have a minimum amount of savings in her account. This distinguishes savers from those who hold accounts solely for the remittance of wages (Demirguc-Kunt and Klapper 2012).

Property ownership enhances women’s economic status, motivating them to save beyond the influence of household wealth. Asset ownership by women also reflects their bargaining power within the household, which can affect their savings behaviour. Scholars argue that a woman’s relative wealth within the household, rather than her absolute assets or wealth, is significantly linked to her savings (Doss et al. 2020).

Empirical research shows that women’s property ownership and wealth status, which strengthen their bargaining power, in turn, influence their formal savings, even when household wealth is controlled for. This is one of the crucial factors that have been overlooked by policymakers in India.

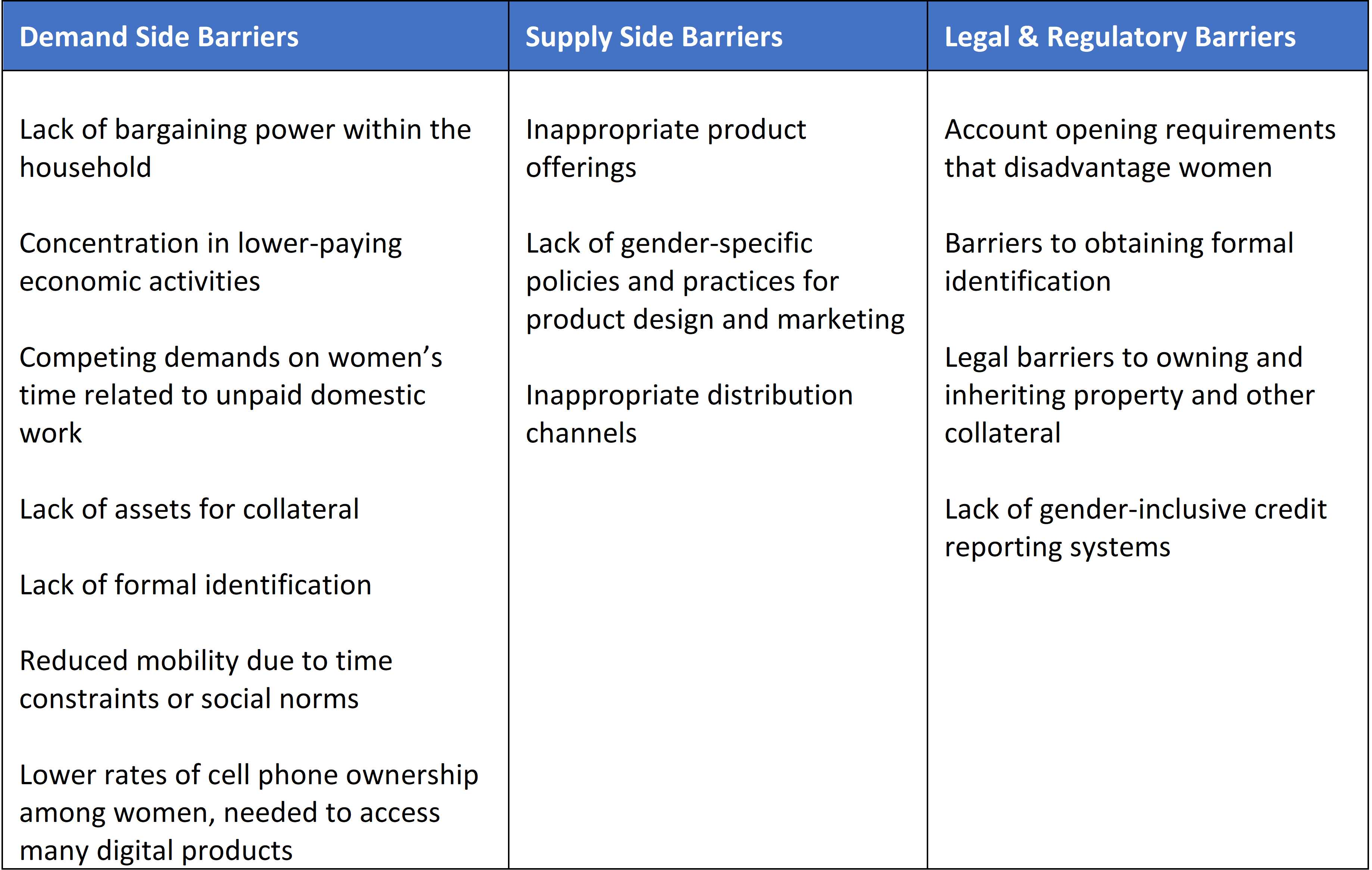

Thus, the numerous barriers women encounter in being financially excluded can be categorised as demand-side barriers, supply-side barriers, and legal and regulatory barriers (Table 1). It has been argued that financial technology or fintech has the capacity to address the barriers women face to being financially excluded.

Table 1: Gender-based Barriers to Financial Inclusion

Bridging the Gender Gap

Fintech refers to the use of technology to offer improved financial services. Digital payments are not new, but recent rapid technological advancements and the rise in global financial flows have increased the focus on financial technology. The link between digital finance and financial inclusion is based on the idea that many underserved and excluded populations own a mobile phone, and that providing financial services via mobile phones and other devices enhances access for these groups.

The Global Findex Database shows that the use of digital payments increased in most countries in Asia and the Pacific from 2014 to 2017. To bridge the gender gap, fintech is supposed to work in several ways.

Has the growth of fintech companies in India made financial services more accessible, affordable, and easy to use? A careful look at the data makes us sceptical.

First, fintech-enabled services will boost accessibility, privacy, and security for women who are unbanked or underbanked. Second, fintech can better evaluate the creditworthiness of individuals who were marginalised in the traditional financial system because they had no credit history or only a limited one. Third, female-headed households and businesses will gain improved access to finance. Finally, women’s time management will improve with fintech, giving them more time for other productive activities.

Has the growth of fintech companies in India made financial services more accessible, affordable, and easy to use? A careful look at the data makes us sceptical.

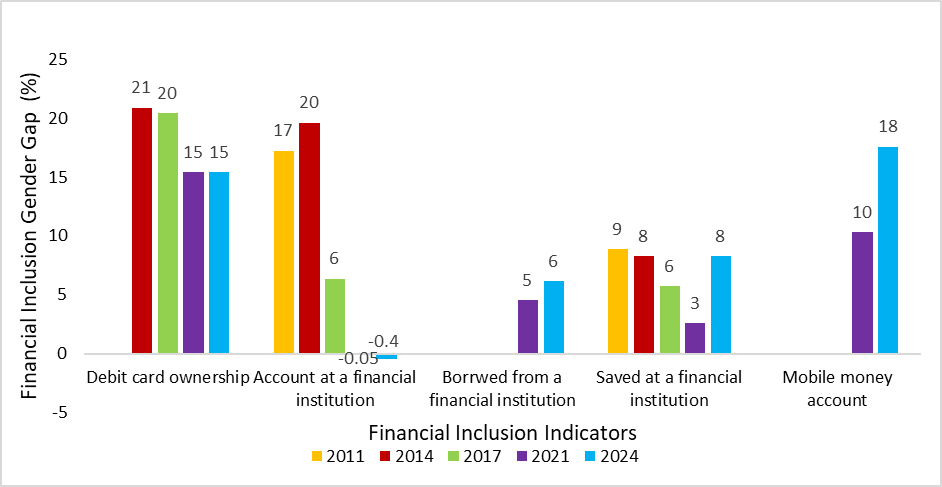

As shown in Fig. 4, even though the percentage of digital payment users has increased, the gap between men and women in digital payments remains large in India. The perceived risks of using fintech are mainly responsible for people’s preference for cash. These risks include cyber-security threats and data breaches that can reveal sensitive personal information and expose consumers to financial fraud.

Additionally, fintech providers may select customers based on their educational levels, potentially excluding those with low financial literacy. As a result, women are likely to be most adversely affected because they generally have lower financial education.

Fig. 4: Trends in Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion in India (2011–2024)

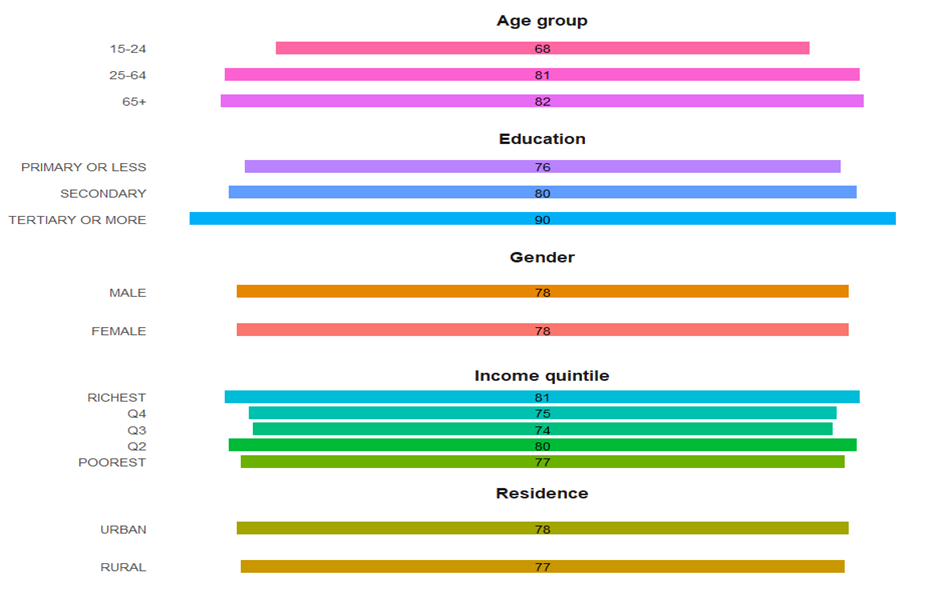

We have broken down the estimates of account penetration by individual characteristics in 2024 in India and presented them in Fig. 5. There is no gender gap in holding formal accounts. However, account penetration varies significantly by age and education.

While 76% of adults with primary education or less has a formal account, the share increases to 90% among those with a tertiary education. Similarly, 68% of young adults have a formal account, compared to 82% of older adults. However, there is no rural-urban gap.

Fig. 5: Percentage of Adults with an Account at a Formal Financial Institution in India in 2024: Account Penetration by Individual Characteristics

Power of Jan Dhan

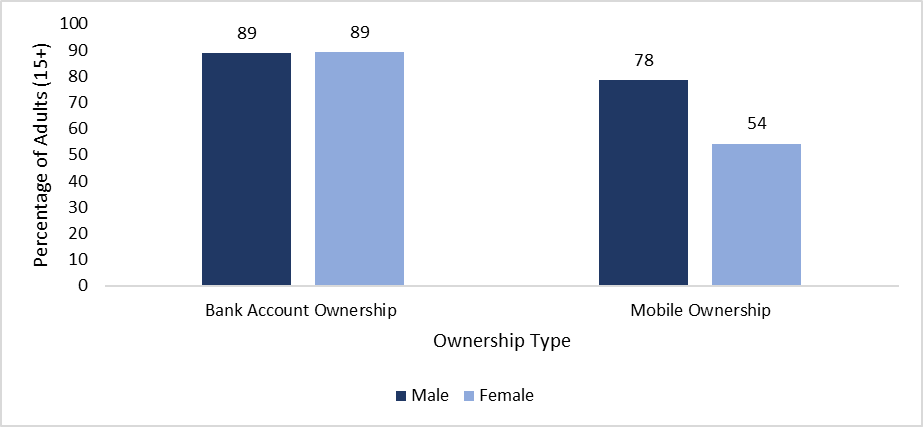

The percentage of women having bank accounts rose sharply from 35% in 2011 to 80% in 2017, and to about 89% in 2024. This increase was largely driven by the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), as shown in the Global Findex 2021 report (see Figure 6). Over the same period, the percentage of men with bank accounts grew from 63% to 89%. As a result, the PMJDY can be credited with significantly reducing the gender gap in bank account ownership.

According to a report by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), a large part of the 200-million women market segment currently operates outside the digital ecosystem.

Studies have reported that nearly all new accounts opened after 2014 were linked to the PMJDY, with 55% of these accounts held by women (Duvendack et al. 2023). However, it is important to recognise that despite the many benefits of the PMJDY programme, 43% of all PMJDY bank accounts remain inactive, and many have negligible balances (Patwardhan 2018).

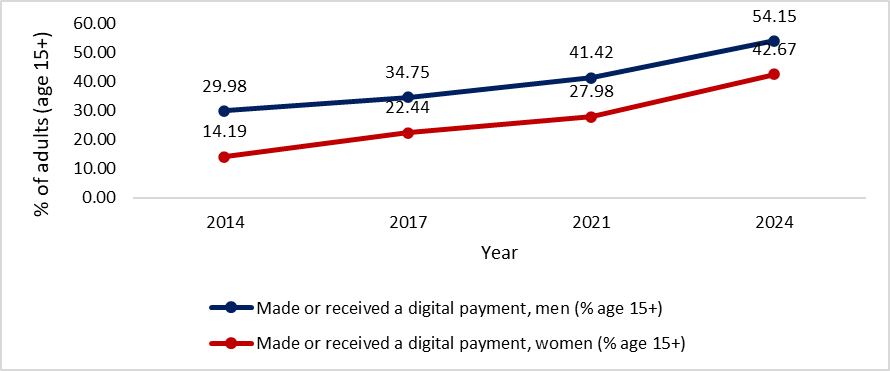

According to a report by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), a large part of the 200-million women market segment currently operates outside the digital ecosystem. The Global Findex data from 2014 to 2024 shows strong growth in digital payment adoption among both men and women aged 15 and above. The share of women using digital payments nearly tripled, while men’s usage increased from 29.98% to 54.15% over the same period (Fig.7). The gender gap in the use of digital payments had come down from 15.79% in 2014 to 11.48% in 2024.

Additionally, the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) among men was higher, averaging 10.33% per year compared to 4.69% per year for women. This indicates that while overall usage increased, men adopted digital payments at a rate more than twice that of women.

Fig.6: Gender Differences in Bank Accounts and Mobile Ownership in India in 2024 (Percentage of Adults 15+)

Fig.7: Gender Gap in Digital Payment Adoption (2014–2024)

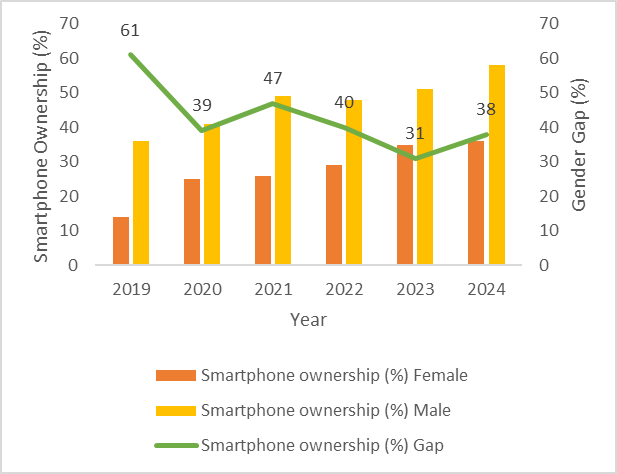

We observe that the slow adoption of digital financial services by Indian women is mainly due to gender gaps in digital access and usage. Compared to men, 24% fewer women own personal mobile phones (Fig. 6), and internet usage is 50% lower. The use of digital financial services by women remains low, as only 32% of Indian women had access to smartphones as of 2024 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Gender Gap in Smartphone Ownership (Percentage)

Conclusions

Despite significant investments in digital finance infrastructure, gender disparities in financial inclusion remain in India. Fintech has improved access to financial services. However, access to financial technology primarily depends on access to digital tools. A significant gender gap exists in access to mobile technology and digital tools, mainly due to social norms and structural barriers. Even when women have access to digital devices, they are less likely to use them for financial services.

This could include appointing female banking correspondents and providing supportive infrastructure, such as communication in local languages and the use of voice and video tools.

Without addressing these fundamental challenges, fintech may risk widening, rather than closing, the gender gap. Research indicates that financial literacy significantly influences women’s bank account ownership. Still, its effect on the use and intensity of other financial products like credit and savings is limited compared to men. This demonstrates that the impact of financial literacy training varies not only in strength but also by the type of financial product and gender.

We argue that simply opening bank accounts for women is not enough. It is essential to strengthen women’s control over their earnings by ensuring that transfers are made into accounts held in their names. Women should also receive training to help them manage their bank accounts and access basic financial services on their own.

In addition to these steps, barriers to women’s participation in the workforce must be addressed, along with efforts to close gender-based earnings gaps, which go beyond just wage differences (Chakraborty and Chakraborty 2010).

To encourage greater involvement of women in financial markets, a gender-sensitive approach is needed. This could include appointing female banking correspondents and providing supportive infrastructure, such as communication in local languages and the use of voice and video tools. Such measures can help overcome women’s reluctance to use technology and make it easier for them to access banking services.

Indrani Chakraborty is HDFC Bank Chair in Banking and Finance, Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi; Archana Meena is Research Analyst, HDFC Bank Chair Unit in Banking and Finance, Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi.