Outsiders and Exclusion

The recent hostility in Assam toward Bengali-speaking migrant workers—especially Bengali Muslims—reflects an intensification of longstanding trends in the state. Hate speech targeting Bengali Muslims and the portrayal of their political participation as “Miyas” (originally meaning “gentlemen,” but now often used pejoratively for Bengali-origin Muslim migrants) have become routine narratives for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has ruled the state since 2016.

In Assam, the label “ghuspetia” (intruder) has long been part of the Hindutva lexicon, which attributes the intrusion to India’s porous border with Bangladesh. In the aftermath of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) debates between 2018 and 2020, the targeting of Muslims—particularly Bengali Muslims—has come to dominate political discourse.

Blaming ghuspetias for Assam’s underdevelopment stems from a chauvinistic perspective, often claiming that Bengali Muslims wield undue economic power (Goswami 2011). This argument, directed at Hindu voters, is a fixture at political rallies in both Assam and West Bengal, shaping election campaigns and echoed by senior leaders, including the Union Home Minister.

The 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War marked a turning point in Assam’s politics, fuelling ethno-linguistic conflict. The influx of refugees from what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) became a central issue in the Assam Movement (1979–1985). Between 1972 and 1979, the voter rolls in Assam increased from 6.3 million to 8.7 million—a rise attributed by some to “intrusion”, a claim that persists in political debate.

Organisations such as the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) and Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) cited this increase as evidence of widespread entry by “foreigners”. As Murshid (2016), following Weiner (1983), observes, such “quasi-genocidal” narratives fuelled ethnic resentment, crystallised in slogans such as “all Muslims are Bangladeshi intruders”.

After the Assam Accord (1986), a variety of statistics were cited to support the idea of “Muslim encroachment”—ranging from higher population growth in border districts, an increase in the Muslim decadal growth rate from about 25% (1961–71) to 30% (1981–91), and a growth in Bengali speakers from 17% (1961) to 27% (2001). Yet Murshid (2016) contends that, over the long term, such figures do not justify allegations of “resource capture” by Muslims.

Ethnic conflict remains central to Assam’s politics (Baruah 2009), but recent years have seen an escalation in rhetoric and, at times, militancy—particularly in border districts like Dhubri, Karimganj, Cachar, and South Salmara. With the resurgence of Hindutva nationalism and the BJP’s rise, the narrative of “infiltrators” looting resources, which peaked during the NRC-CAA debates, continues to frame contemporary politics.

Economic Status and Identity

This article examines “economic citizenship”—how religious and linguistic groups fare on key economic indicators. If the concern is “resource looting”, then economic citizenship is a more relevant measure of actual group influence than marginal changes in population. We use the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) developed by Alkire and Foster (2011), combining education, health, and standard of living indicators.

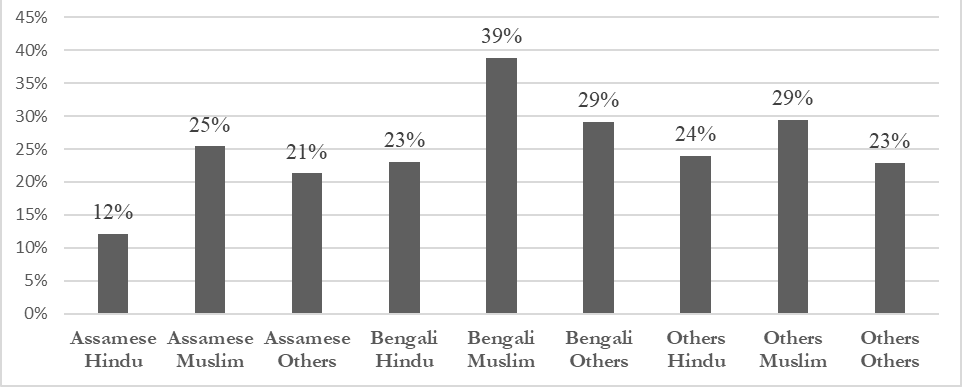

The headcount ratio for multidimensional poverty in Assam is notably high for some groups (Figure 1). Muslims—whether Bengali, Assamese, or other-language speakers—are disproportionately affected. Strikingly, 39% of Bengali-speaking Muslims are multidimensionally poor, the highest among all groups, compared to about 12% of Assamese Hindus. This directly challenging the “resource loot” narrative.

Figure 1: Poverty Head Count Ratio of Different Ethno-Linguistic Groups in Assam (in %, 2019-21)

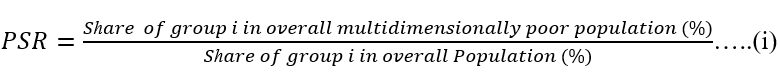

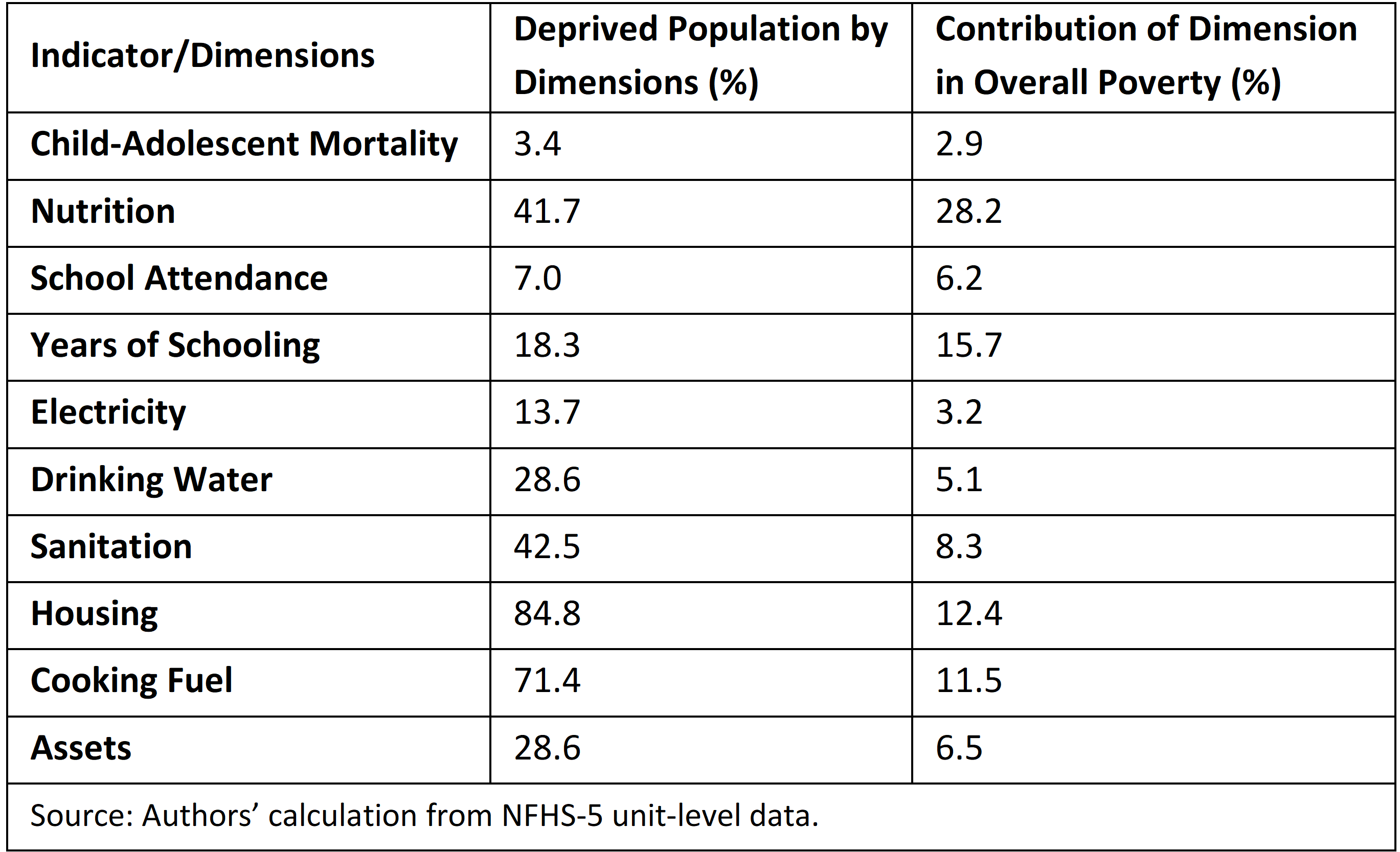

But simple comparisons of poverty rates do not suffice. It is also necessary to consider each group’s proportion in the total population. To do this, we calculate a Poverty Share Ratio (PSR) for every ethno-linguistic group in Assam (2019–2021). This ratio captures a group’s share of the poor relative to its population share. A PSR over 1 indicates a disproportionate burden of poverty.

First, only three groups do not experience disproportionately high multidimensional poverty—Assamese-speaking Hindus, Assamese-speaking non-Hindus, and Bengali-speaking members of other religions. Of these, the latter two constitute a very small share of the overall population (Table 1).

Table 1: Poverty Share Ratio of Ethno-linguistic Groups in Assam (in % and ratio, 2019-21)

Second—and perhaps most importantly—Muslims across all language groups, and especially Bengali-speaking Muslims, experience significantly higher rates of poverty compared to other religious communities (Table 1). Although Bengali-speaking Muslims make up only about one-eighth (14%) of the population, they account for nearly one-fourth of all people living in poverty.

This stark disparity merits deeper investigation. Specifically, which components of the multidimensional poverty index are driving this high poverty rate? And is there a notable regional pattern to Muslim poverty, for both Bengali- and Assamese-speaking groups?

Poverty’s Roots

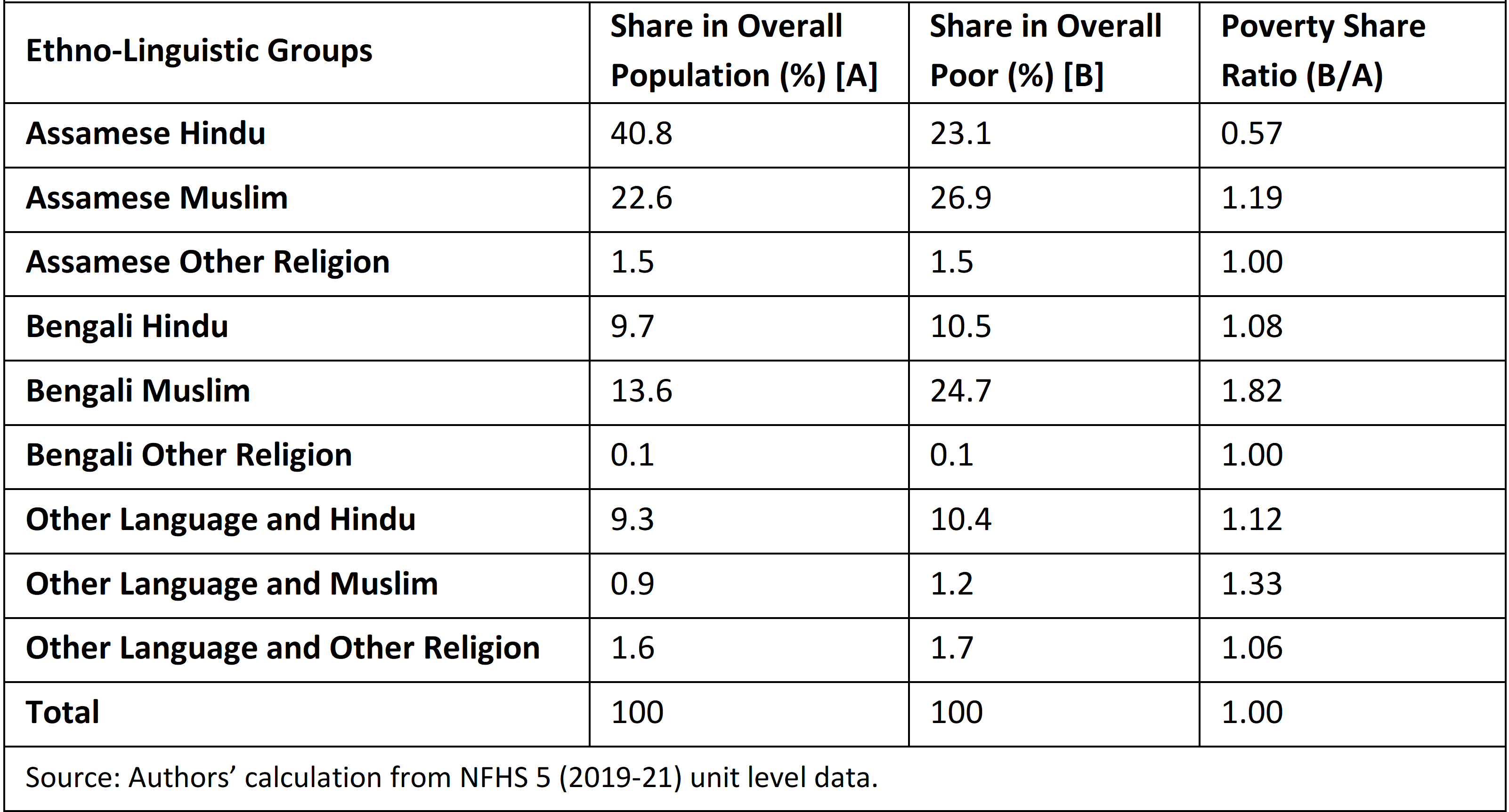

Nearly 85% of Bengali Muslims live in poor housing, and 71.4% lack access to clean cooking fuel. Two common accusations directed at Bengali-speaking Muslims—believed to be refugees from Bangladesh—are that their high migration and fertility rates have led to significant settlement in Assam, and that they have laid illegitimate claim to land. Yet the data shows that, even if these accusations held, Bengali Muslims have not materially benefited in terms of housing or sanitation—42% still lack basic sanitation (see Table 2).

Table 2: Contribution of Each Indicator in the Multidimensional Poverty of Bengali Muslims in Assam (2019-21)

Of all components in the multidimensional poverty index, poor nutrition makes the largest contribution to deprivation among Bengali Muslims, followed by limited years of schooling. This pattern suggests institutional discrimination (Bansode and Swaminathan 2021), with government entitlements such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) and public distribution system (PDS) remaining out of reach, particularly in villages dominated by marginalised groups.

Hate as Strategy

The rise of hardline Hindutva politics—especially in regions still marked by Partition—has tilted local discourse toward the systematic “othering” of certain communities (Anderson and Jaffrelot 2020). In Assam, these practices are intensified by deep-seated ethnic tension and government neglect.

Politicians often resort to hate speech for electoral gain, inflating the perceived threat of “intruders.” This rhetoric echoes slogans like “Hindu Khatre Mein Hain” (“Hindus are in danger”) used by the Hindu right to consolidate power.

Yet the facts on the ground in Assam show that Bengali Muslims face severely restricted social mobility and have very little opportunity for economic advancement. Far from posing a threat to dominant groups, Bengali Muslims remain trapped by persistent barriers that limit hope for improvement.

The authors thank Sheetal Bharat, Abhishek Shaw, and Kaushik Bora for their valuable comments. The views expressed here do not reflect the opinions of the institutions to which the authors are affiliated.

Subhendu Khan (subhendu@isec.ac.in) is a doctoral scholar at the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. Soham Bhattacharya (soham.bhattacharya@krea.edu.in) is a postdoctoral scholar at the Moturi Satyanarayana Centre for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences; KREA University.