This year marks the centenaries of two organisations that are polar opposites in ideological terms: the Communist Party of India and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. We may also note the centenary of an organisation that represented a world-view distinctly different from either of them.

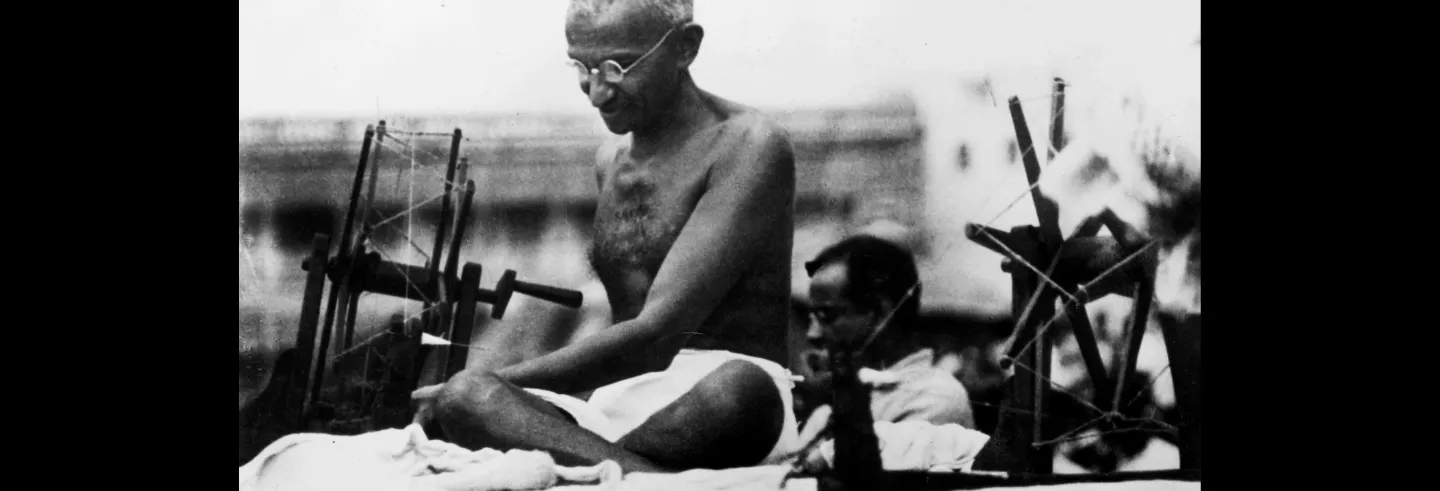

In September 1925, Mahatma Gandhi founded the All-India Spinners Association, or Akhil Bharat Charkha Sangh, to carry out his agenda for khadi. Gandhi argued that the time had come for “a permanent organisation, unaffected and uncontrolled by politics, political changes or political bodies” (1925c)—that is, one that was independent of the Congress.

For Gandhi, swaraj or freedom extended beyond the end of colonial rule to encompass the social and economic emancipation of the ordinary Indian.

To understand Gandhi’s motives in taking his khadi endeavours outside the Congress mainstream, we need to briefly recapitulate the story of khadi in the preceding years. As is well recognised, within a few years of returning to India in 1915, Gandhi had come to dominate nationalist politics. In part, this rapid ascent was owed to his exceptional ability to mobilise the masses.

But Gandhi was not merely interested in drawing on public support for the campaign against the Raj. He was equally—if not more—concerned with building a durable, non-violent social order. This necessitated addressing the multiple problems that plagued Indian society because there could be no peace without justice and equity.

Throughout his life, Gandhi devoted much attention to the task of ‘constructive work’. During the 1920s, his constructive efforts focused mainly on three fronts—a campaign against untouchability, promotion of Hindu-Muslim amity and the development and propagation of khadi or handspun, handwoven cloth.

As early as 1908, Gandhi had felt that “without the spinning wheel there was no Swaraj” (1928). For Gandhi, swaraj or freedom extended beyond the end of colonial rule to encompass the social and economic emancipation of the ordinary Indian.

Owing to the novelty and success of his early political campaigns, khadi witnessed an explosive growth in public consciousness. By 1921, the charkha—the spinning wheel—was incorporated into a prototype Congress flag. At the same time, the ‘cult of the charkha’ had its critics, most notably Rabindranath Tagore. Many others opposed khadi on economic and modernist grounds.

The Non-Cooperation Movement of the early 1920s included the boycott of colonial educational institutions, courts and councils or legislatures. Following the mob killings at Chauri Chaura, Gandhi halted this movement. He was arrested, tried, and sentenced to prison in 1922. With Gandhi behind bars, the Congress was split between ‘no-changers’, who adhered to non-cooperation with the government, and ‘pro-changers’, who sought to enter legislatures under the aegis of the Swaraj Party. In 1924, Gandhi was released early from prison following an emergency appendectomy.

After abruptly ending the political campaign in 1922, Gandhi had to face a Congress riven with dissension, corrupt practices and jostling for power. Many leaders were uninterested in the constructive programme of the Congress and did not share Gandhi’s position on non-violence either. They pressed for a re-engagement with the institutions of the Raj.

Many people wore khadi to express their will to freedom, but most Indians did not embrace its underlying principle of economic decentralisation.

Gandhi and the ‘no-changers’ wanted to emphasise constructive work rather than joining legislatures with limited authority. Despite prolonged negotiations, the two groups remained at odds. In order to wrest the initiative, Gandhi introduced a contentious policy—Congress members were required to spin for half an hour daily and submit good quality handspun yarn regularly.

Because of Gandhi’s pre-eminent position, the ‘spinning franchise’ became official Congress policy. However, most leaders and rank-and-file members largely ignored it in practice. Gandhi soon realised that his radical test of commitment to constructive work was a dead letter. He quickly reversed course, conceding perhaps more than the situation required.

The spinning franchise was repealed and a division of labour was agreed upon. The Swarajists would contest elections to enter the legislatures while the rest of the Congress would focus on constructive work. Gandhi also accepted a term as president of the Congress in late 1924. He spent most of 1925 travelling across the country and campaigning on the three items of constructive work mentioned earlier.

By forcing the issue on spinning as a means of identification with the masses, Gandhi was foregrounding the question of the purpose of politics. Yet, the spinning franchise debacle made one thing clear—although the Congress would never dare to repudiate Gandhi, it had no genuine commitment to his constructive programme. 1As Gandhi himself noted, “The Congress did accept the charkha. But did it do so willingly? No, it tolerates the charkha simply for my sake". See 'Speech at A.I.S.A. Meeting – III', 3 September 1944. The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (1979), Vol. 78, p. 75, Delhi:The Publications Division.

In turn, Gandhi remained committed to his programme of social reconstruction but could not disown the Congress, the only vehicle for mass mobilisation towards political freedom. This pas de deux, or delicate dance, continued throughout his life.

The founding of the spinners’ association in 1925 had mixed outcomes. The Congress avoided a major crisis and was preserved to fight another day. Gandhi could protect his khadi agenda from the political vicissitudes of the Congress, but it came at a significant cost. Delinked from the edifice of the party, khadi evolved in a number of ways that we do not detail here.

Many people wore khadi to express their will to freedom, but most Indians did not embrace its underlying principle of economic decentralisation. Ironically, after Independence, khadi and village industries became an appendage of the vast apparatus of the Indian state that remains fundamentally hostile to Gandhi’s ideals of economic self-reliance.

For Gandhi, khadi stemmed from a recognition that agriculture alone could not provide adequate sustenance for the millions of rural Indians who needed to earn a livelihood through work. Thus, the primary challenge was to provide “dignified labour for the millions” that lacked education, assets or skills (1925a). Gandhi argued that the “charkha provides such labour. Till a better substitute is found, it must, therefore, hold the field". In other words, khadi was not an end in itself nor an antediluvian fetish as many would have it. Rather, it was a pragmatic response shaped by the necessity and constraints of the times.

In answering numerous criticisms, Gandhi repeatedly argued that spinning only afforded a supplementary income and was not meant to meet all the financial needs of workers. 2In the 1930s, Gandhi recognised the limitations of khadi and expanded the scope to village industries as well. Nevertheless, for the poor, any additional income was of great value.

The spinners’ association was also alert to the vexatious complexity of economic life. For instance, in the 1930s, Gandhi pressed a reluctant spinners’ association to raise their standard wages. Predictably, the consequent increase of the price of khadi led to a drop in sales and helped the ingress of fake khadi made by textile mills, thereby endangering the whole enterprise.

This state of affairs resonates with the Gandhian warning that “centralisation of industries is inimical to the development of democracy in politics”.

Gandhi also readily accepted that khadi or any other low-investment manufacture could not compete against industrial production backed by capital and state patronage. Nevertheless, he categorically rejected large-scale industrialisation as a solution because it inevitably would lead to an economic dominance that would strip the vast majority of their autonomy. Given the eye-watering levels of economic inequality in contemporary India, one is reminded of Gandhi’s poser—“What is industrialism but the control of the majority by a small minority?” (1925b).

In a related sense, the unprecedented concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few business houses has been harmful to India’s economy and, in recent days, to its foreign policy as well. This state of affairs resonates with the Gandhian warning that “centralisation of industries is inimical to the development of democracy in politics” (Kumarappa 1946).

It is for similar reasons that Gandhi remained sceptical of the emancipatory potential of sophisticated machinery. He succinctly outlined his position to an interlocutor,

I would prize every invention of science made for the benefit of all. There is a difference between invention and invention. I should not care for the asphyxiating gases capable of killing masses of men at a time. The heavy machinery for work of public utility which cannot be undertaken by human labour has its inevitable place, but all that would be owned by the State and used entirely for the benefit of the people. I can have no consideration for machinery which is meant either to enrich the few at the expense of the many, or without cause to displace the useful labour of many (Desai 1935).

Apart from its historic relevance, the All India Spinners Association and the inflection point of 1925 is of significance in our time. A number of considerations that animated Gandhi’s economic agenda prevail in contemporary India, albeit in a modified form.

For Gandhi a non-violent society was not merely marked by the absence of political or social violence. Rather it also delivered justice and equity in one’s individual and social life. As we have seen, Gandhi’s attempts at establishing an organic connection between mass politics and social reconstruction were met with indifference and hostility. However, the slow, painstaking, and unglamorous work of social and economic transformation remains a vital element in any mature democracy.

The contemporary Indian economy is markedly different from that which prevailed in 1925. However, a majority of Indians continue to seek work that affords dignity and adequate remuneration. The fundamental questions raised through the khadi movement remain unanswered. To address the many challenges it faces today, India needs to draw on the hard-earned lessons of khadi and the spinners’ association.