A new Malayalam movie, Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra, is creating a sensation across India. Critics and industry experts have hailed it as Indian cinema’s first true “superwoman movie”. The film has not only captured the attention of audiences but also sparked discussion about how the comparatively small Malayalam film industry has achieved such technical excellence and commercial success—all without relying on male stars in leading roles.

The Malayalam film industry remains nimble, adaptable, and flexible in its production processes and organisation—especially during times of crisis.

This brings us back to the same kind of questions that have been asked in post-Covid-19 times—what is it that makes Malayalam cinema special? Why is it getting so much global and national attention? What is it that makes Malayalam cinema different from other Indian cinemas?

Unlike what many new admirers of Malayalam cinema seem to think, this is not something that happened out of the blue. But it took a pandemic for the world to sit back and notice it. Covid-19 made film production and exhibition came to a standstill across the country. But Malayalam cinema found an opportunity to stand out during this time, with many films achieving major success on OTT platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and Disney+, attracting viewers across India and around the world.

Malayalam cinema’s success reached such heights that even international media—usually focused exclusively on Bollywood—began to take notice. The Guardian called Malayalam cinema “the most dynamic of all India’s multiple regional producers”, and the New Yorker described Joji (2021) as “the first major film of the Covid-19 pandemic”.

Looking beyond the Covid-19 moment, it is clear that several factors—industrial, socio-economic, and aesthetic—played a role in this rise, especially at a time when big production houses and large crews were inactive.

Historically, the Malayalam film industry has been prolific in terms of the number of films produced every year—from an annual average of about 125 films in the 1980s, declining to just over 90 films per year in the following 20 years, before rising sharply to around 150-200 films a year during the first two decades of the new millennium. Although Malayalam films make up about 9% of the movies produced in India, they contribute less than 5% of the country’s total box-office revenue.

This “high production, low revenue” paradox highlights the industry’s limited economies of scale. However, it also means the Malayalam film industry remains nimble, adaptable, and flexible in its production processes and organisation—especially during times of crisis. Most Malayalam films released through OTT during the pandemic were made with a small budgets and crew, in single locations, and with minimum facilities.

Openness is visible not only in Kerala’s famous left-leaning, internationalist political traditions but also in its vibrant culture of translation, public libraries, and film societies.

Most importantly, stars like Fahad Faazil and Tovino Thomas were willing to join these projects. This helped the Malayalam film industry remain agile during the pandemic, unlike other film industries in India, which faced major production challenges due to their large infrastructures, rigid establishment set-ups, and mega stars who are institutions in themselves.

The Malayalam industry’s flexible and lower scales of production gave it a unique advantage, making it easier to adapt to changing conditions. This flexibility went beyond production size—it also extended to the choice of themes. Malayalam cinema mostly explores cosmopolitan ideas and has a diverse range of stories, which makes it appeal to audiences outside its own language and region.

In essence, Malayalam cinema’s versatility stems from three key factors—its nimble production process, its diverse themes that reflect a pluralistic society, and its cosmopolitan, global outlook.

Plural Society, Secular History

Malayalam cinema’s uniqueness is rooted in several historic and demographic factors. These influences have shaped its universal vision and pluralistic style of storytelling.

Key factors include religious diversity, a multicultural society, and widespread literacy. The region’s long cosmopolitan history—marked by maritime trade, waves of colonial influence, and ongoing migration—has led to a sizeable Malayali diaspora around the world.

These voluntary and sometimes compulsory connections with the outside world shape all aspects of Malayali culture. This openness is visible not only in Kerala’s famous left-leaning, internationalist political traditions but also in its vibrant culture of translation, public libraries, and film societies.

Such traditions have laid the foundation for popular international cultural events, including the International Film Festival of Kerala, Kochi Muziris Biennale, and various international theatre and literature festivals. These events are supported by steady, significant state investment in art and cultural academies.

Such engagements have enabled the local cultural imagination to keep pace with global trends in arts and ideas. As in literature, arts, and politics, Malayalam cinema too, right from its beginnings, was defined by a secular, pluralistic ethos, and concern for social equality. When all Indian cinemas were going through a bhakti/sant film wave in the post-Independence decades, Malayalam cinema stood apart, grappling with social justice and class inequality. Not many “patriotic” films were made in those years, though there were some popular nationalist songs.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Malayalam cinema became both a thriving industry and a major cultural force. Its direction was deeply influenced by literature and social-realist themes. Nearly all the iconic films from this era were adaptations of literary works or featured scripts by renowned writers. Trailblazers such as P. Bhaskaran, Ramu Kariat, K.S. Sethumadhavan, and Vincent established the distinctive styles—visual, musical, acting, and narrative—that defined Malayalam cinema for years to come.

The 1990s was a decade of liberalisation, rising communal politics, and the arrival of television, each leaving its mark on society and the entertainment industry.

In the 1970s, a 'new wave' of young directors—including Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G. Aravindan, K.R. Mohanan, and John Abraham—transformed Malayalam cinema. They introduced fresh cinematic and visual styles, as well as new acting and technical talents, who were soon embraced by mainstream filmmakers. The 1980s marked the industry’s golden age. Investment from expatriates in the Arabian Gulf led to a surge in film production, expanding both the range of genres and the ambition of storytelling. Notably, the first 3D film in India was made in Malayalam, not in the larger Hindi, Telugu, or Tamil industries.

What sets Kerala’s film industry apart is that, even during periods of commercial growth, it maintained a remarkable diversity of content. At one end of the spectrum were “art” films, which rejected typical commercial elements such as songs, dances, stunts, and melodrama. At the other were large-scale, multi-star blockbusters directed by filmmakers such as I.V. Sasi, Joshy, and Sasikumar. Between these extremes was the highly popular “middle cinema” made by directors like Padmarajan, Bharathan, and K.G. George. Most importantly, each of these different streams attracted dedicated audiences, who had not yet been split into separate categories such as youth, family, or mass viewers.

Era of Change

The 1990s marked a turning point for Malayalam cinema. This was a decade of liberalisation, rising communal politics, and the arrival of television, each leaving its mark on society and the entertainment industry. While art cinema maintained a niche following, commercial films suffered, especially with the growing popularity of international TV programming and tele-serials.

Faced with these changes, the Malayalam film industry retreated into two main genres—full-length comedies (often inspired by the popular mimicry shows of the time) and soft-core erotica. This shift was, in many ways, a response to globalisation and the industry’s limited resources. Unable to match the technical sophistication and spectacle of big productions from outside, Malayalam filmmakers focused on humour and erotica, genres that always found an audience locally.

While these directors drew inspiration from global visual culture and narrative trends, their themes remained deeply rooted in Malayali life and values.

With the advent of television, the family audiences who had once filled cinemas began to stay home. Cinema soon became dominated by male-oriented themes, often featuring macho and communal heroes, while television turned to female viewers, with a proliferation of mythological and saas-bahu serials.

In Malayalam cinema, this era saw the rise of the majoritarian, macho hero and the cult of the superstar. The industry, which had previously invested in strong stories and visionary directors, now placed its bets almost entirely on stars—most notably Mammootty and Mohanlal. Television channels played a key role in amplifying this celebrity culture.

In the two decades following the Babri Masjid demolition and the Mandal riots, Malayalam cinema lost much of its secular spirit and cosmopolitan outlook.

However, this phase did not last. With the arrival of the digital era and a new generation of filmmakers, Malayalam cinema has found a fresh direction. These filmmakers have shifted the focus to stories grounded in everyday life, featuring ordinary people and their daily struggles at the centre of their narratives.

New-Generation Cinema

The commercial foundations of Malayalam cinema was first shaken by television, which shifted revenue streams from box office collections to TV ratings. Film narratives increasingly followed television industry preferences, with star power becoming the sole guarantee of success—relegating stories and directorial vision to secondary importance.

The digital revolution, however, brought far more radical change. It transformed every aspect of filmmaking, from scripting to exhibition, while dismantling the centralised celluloid structure and television’s dominance. The new millennium saw an influx of 'small' films, particularly by young filmmakers comfortable with emerging technologies and formats.

While these directors drew inspiration from global visual culture and narrative trends, their themes remained deeply rooted in Malayali life and values. They focused on the ordinary—everyday conflicts, dilemmas, and struggles of common people. Most significantly, these films freed Malayalam cinema from macho, superstar-driven narratives, and the narrow focus on upper and middle-class social spaces.

This movement has introduced a new generation of technicians and actors, including Fahad Fazil, Dulquer Salman, Joju George, Parvathy Thiruvothu, Tovino Thomas, Vinayakan, Nimisha Sajayan, Chemban Vinod, Soubin Shahir and Basil Joseph. It has also revitalised veteran actors like Indrans and Jagadish, who had previously been confined to supporting roles.

Compressed Time

An interesting shift introduced by the new-generation movies was the compression of time within their narratives. The macho superstar films of previous decades operated within an expansive sense of time—they often looked nostalgically to the past, sought to settle old scores, pursued revenge or romance in the present, and dreamed of a happy future.

In contrast, the new-generation narratives compress time. Events simply 'happen'. Unpredictable incidents, accidents, chance meetings, and random encounters propel stories forward. Time shrinks to the immediate present, with narratives often unfolding at a breakneck, 'pressure cooker' pace.

This trend began with films like Traffic (2011, Rajesh Pillai) and Chappa Kurisu (2011, Sameer Thahir). It continued with several successful titles, such as Ishq (2019, Anuraj Manohar), and S Durga (2017), Ozhivudivasathe Kali (2015), and Chola (2019) by Sanal Kumar Sashidharan. Other notable examples include Ee. Ma. Yau (2018), and Jallikattu (2019), directed by Lijo Jose Pellissery. Aabhasam (2018) by Jubith Namradath and Randu Per (2018) by Prem Sankar.

With the absence of inner ethical conflict and narrative resolution, life in these 'liquid' stories is a continuous state of excitement and thrill, but ultimately leaves a sense of moral emptiness.

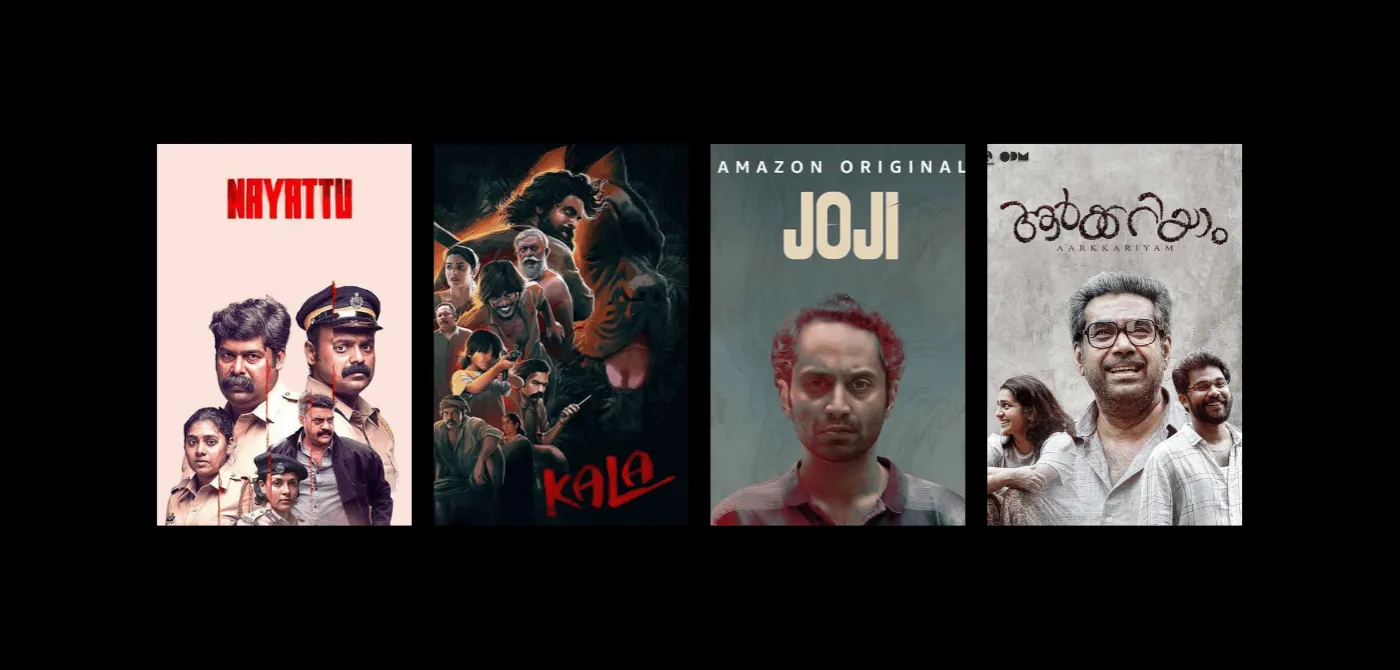

Dileesh Pothan’s Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum (2017) and Joji (2021) received much acclaim. Additionally, Kala (2021) by Rohith V.S., Arkkariyam (2021) by Sanu John Varghese, and Nayattu (2021) by Martin Prakkat contributed to this movement. More recently, films such as Pravinkoodu Shappu (2025, Sreeraj Srinivasan), Gaganachari (2024, Arun Chandu), and Ronthu (2025, Shahi Kabir) have carried this trend forward.

When time is compressed in these narratives, history and memory become irrelevant. Everything unfolds in the immediate present, with only instant reactions and reflexes mattering—legacy, past experiences, and future aspirations fade away. Both the story and its characters are trapped in the urgency of now. In this timeless, amoral space, heroes do not act purposefully; they merely react to external stimuli like threat, lust, greed, or revenge—leaving little room for ethical considerations.

Ethical imagination requires a sense of time, where past wrongs haunt the present and shape the future. Without temporal depth, these stories offer no chance for self-reflection, guilt, or repentance. Ideals that depend on the passage of time—like justice, history, trust, love, and compassion—disappear. In this tense and enclosed atmosphere, violence becomes the dominant form of response and expression.

With the absence of inner ethical conflict and narrative resolution, life in these 'liquid' stories is a continuous state of excitement and thrill, but ultimately leaves a sense of moral emptiness. Murders are committed and forgotten, parricide is plotted and executed, and enemies are destroyed, all without remorse. It is no surprise, then, that most contemporary films are set in police stations and revolve around crime and revenge.

Elaboration of Space

Another result of compressed time in new-generation films was a greater focus on space—most of these acclaimed movies are deeply rooted in their locations. The list is extensive—Kumbalangi Nights, Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum, Ee. Ma. Yau, Jallikattu, Angamali Diaries, Idukki Gold, Maheshinte Prathikaram, Bhramayugam, and many more. This shift marked a welcome departure from the narrow, caste-bound, and upper or middle-class settings that dominated earlier narratives.

Instead of presenting locations as merely lyrical or nostalgic, these films depict spaces filled with sexual tension, struggles for survival, caste divides, and potential for violence. The stories are centred on ordinary men and women living in varied landscapes and communities, no longer revolving solely around powerful alpha males.

Filmmakers of the post-liberalisation era embraced digital technology and the social media environment, free from the ideological constraints of their predecessors.

Filmmakers of the post-liberalisation era embraced digital technology and the social media environment, free from the ideological baggage of their predecessors. Their films confront the realities of our post-truth, media-saturated, and anxiety-driven times, where old conflicts—related to class, caste, and gender—take on new forms and complexities.

Notable among these are Take Off (2017, Mahesh Narayanan), Chavittu (2022, Sajas and Shinos Rahman), and Prappeda (2022, Krishnendu Kalesh), which premiered at Rotterdam and won several international awards. Other important titles include Vrithakrithyilulla Charthuram (2019), as well as Avasavyuham (2022) and Purusha Pretham (2023) by Krishand.

Parallel Cinema

Despite the widespread acclaim for Malayalam movies, parallel and art films that are regularly produced these days often go unnoticed. Over the past decade, many independent filmmakers working outside the commercial theatre, television, and OTT industries have been creating significant work in Kerala. Directors such as Dr Biju, Sanalkumar Sasidharan, Vipin Vijay, Don Palathara, K.R. Manoj, Shalini Usha Nair, Santosh and Satish Babu Senan, K.P. Sreekrishnan, Vinu Kolichal, Sudevan, Midhun Murali, Krishand, Fazal Razak, Tara Ramanujam, and Siva Ranjini are just a few examples.

Their films tackle issues of time, space, caste, and gender in ways that are politically important, aesthetically challenging, and thematically rich. However, because these films do not follow the typical new-gen pace or style—or sometimes do not tell conventional stories at all—they are largely sidelined.

They receive little attention from mainstream platforms and are often intentionally excluded from OTT services, resulting in only marginal or token visibility. Even critics have been slow to acknowledge the value or presence of these independent films.

Rupture in Misogyny

A landmark moment in Malayalam cinema was the formation of the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC) in 2017 after a shocking attack on an actress. For the first time, women in the industry organised to challenge its patriarchal norms, prompting the government to launch an official inquiry into widespread harassment and gender-based discrimination in the Malayalam film industry.

Malayalam cinema’s roots reveal a long history of misogyny, starting with its first heroine, P.K. Rosy, a Dalit woman. After starring in Vigathakumaran (1928), the first Malayalam silent film, Rosy was driven out of the city by moral vigilantes simply for acting alongside a male lead. Looking back across a century of Malayalam cinema, this incident stands as a stark reminder of persistent gender inequality both on screen and behind the scenes.

Despite significant media and public outcry [on the Hema Committee], no one has been held accountable and no meaningful action has been taken, aside from some changes in organisational leadership.

The creation of the WCC marked the first concerted effort by women to confront these entrenched structures. Since then, there has been greater caution in portraying explicit misogyny or gender bias in films, especially among younger filmmakers.

The Hema Committee that looked into discrimination in the Malayalam film industry released its report in 2019. The report featured firsthand accounts from women across all areas of filmmaking, revealing shocking cases of exploitation and abuse. Subsequently, several women publicly named their abusers—including a sitting member of the assembly (MLA) and senior office bearers of film organisations.

Despite significant media and public outcry, no one has been held accountable and no meaningful action has been taken, aside from some changes in organisational leadership. As with the initial case that prompted these events, most complaints remain mired in legal delays and procedural hurdles.

Although the WCC has not led to improvements in service conditions, fair pay, or workplace policies, it has unsettled the traditionally masculine core of Malayalam film narratives. In response to women’s growing assertion, many films now avoid featuring women altogether. Successful titles such as Aavesham, Manjummal Boys, Premalu, and Romancham focus exclusively on male characters and celebrate male camaraderie.

The Challenged Hero

While the WCC challenged male dominance in the industry, the traditional male hero was already under threat in the new-generation narratives. Earlier, superstar heroes took charge, controlled their women, and ruled over families and destinies. By contrast, new-gen protagonists find themselves in chaotic, uncontrollable worlds. They land in violent or unpredictable situations by chance and can only recoil, respond, or react.

For instance, these characters flee a broken system (Nayattu), fight desperately to survive against a dangerous rival (Kala), conspire in the murder of a parent (Joji), or become complicit in someone else’s crime (Arkkariyam), The era of the tragic or romantic “veera-nayaka” hero has ended. Actions are no longer premeditated but are desperate, impulsive responses to immediate crises and shrinking spaces. These new heroes are fragile and vulnerable, yet also prone to violence.

Of course, the earthiness of Malayalam cinema—the focus on everyday situations and its naturalistic acting style—also plays a major role in drawing a pan-Indian audience.

Notably, their weakness is often heightened by the intimidating presence of a domineering father figure. In films like Arkkariyam, Joji, Kala, and Appan, these fathers loom over the protagonists—ghosts from the superstar era—reminding us of a time when macho heroes controlled the narrative. This deep crisis of masculinity becomes even more significant as women’s voices gain prominence in Malayalam cinema.

This atmosphere of masculine uncertainty and indecisiveness also reflects a broader politico-economic context marked by ongoing crises and unexpected upheavals—economic, political, social, and even biological. For example, the announcement of demonetisation disrupted livelihoods and upended family budgets. The imposition of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) cast doubts over individual citizenship. The constant threat of devastating floods and landslides, as well as the pandemic that exposed the fragility of human life, have all contributed to a pervasive sense of unease.

These random but recurring events create deep uncertainty that matches the compressed, high-pressure feel of new-generation movies. This shared experience may explain why non-Malayali viewers also connect so easily with these films.

Of course, the earthiness of Malayalam cinema—the focus on everyday situations and its naturalistic acting style—also plays a major role in drawing a pan-Indian audience. This appeal has even turned an otherwise unassuming actor like Fahad Fazil into a national sensation. The conflicted, ambivalent characters he portrays—individuals struggling with uncertainty and temptation in an unpredictable world—seem to resonate with audiences anywhere.

Afterword

Malayalam cinema is undoubtedly experiencing a creative burst, with its engaging stories attracting both national and international attention, as well as critical acclaim. Given this success, it is worth asking—have Malayalam films truly fulfilled the cosmopolitan hopes and secular ideals of Malayali society?

While the versatility and dynamism of new-generation cinema are impressive, there is also concern about its disregard for history and its preoccupation with violence. Many films seem fixated on revenge, unfolding within compressed timelines and claustrophobic settings. The question remains whether the new generation of Malayalam filmmakers can summon the political and artistic energy needed to break algorithmic pressures and challenge the darker forces that seem to be shaping our era.

C.S. Venkiteswaran is a film critic, curator, and translator based in Kerala.