Some eight and a half years ago the World Bank Commission on Global Poverty, presided by the late Sir Tony Atkinson, made 21 recommendations for improving upon the World Bank’s method of measuring global poverty. The Commission had recommended not to change the poverty line until 2030, but the World Bank has updated the poverty line twice since; with the recent update for 2025 showing a worrisome addition of 200 million people living in conditions of extreme poverty. This gap is second only to the 2005 update of the international poverty line which resulted in a jump by 400 million people. This is not an unexpected turnout, but a problem bound to occur based on the conceptual core of the World Bank’s approach. The World Bank’s partial acceptance of the recommendations of the Commission on Global Poverty indicates that the measurement of global poverty appears to be a domain where institutional inertia and pristine methodological recommendations tend to clash.

Why does it matter?

Showing how close the world is to becoming free of poverty is an important feat. By implication, the importance of poverty measurement increases hand in hand. The so-called dollar-a-day approach, used by global institutions to track global poverty since 1990, has been shown to suffer from a high degree of uncertainty, and that it fails to track comparable living standards across countries, and across time (Reddy and Pogge, 2010; Moatsos, 2016; Allen, 2017).

High uncertainty means that we cannot be reasonably certain about the extent to which the situation on a global scale is improving or becoming worse across consecutive years. It also implies a large degree of uncertainty in the geographical spread of poverty across the globe. The lack of comparability of living standards that the international poverty line actually tracks across time and countries, does not allow much confidence when we are interested in the relative degree of progress across countries and across time.

A thought experiment can be telling of what is basically wrong with the method used by the World Bank to track global poverty.

Measurement is a very appealing idea. It certainly feels that we know something better if we can measure it. But the degree to which something is measurable and to what extent, can be deceiving. Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals encapsulated the assumption that poverty can be measured from a global standpoint. Despite how debatable that premise may be, the dollar-a-day methodology falls short in its task in several serious ways. Despite its jumpy and inconsistent nature, it supports the illusion that we do know the exact extent of global poverty across countries.

On this the World Bank Commission on Global Poverty was not silent, but issued a recommendation advising the World Bank to establish cooperation in order to capture the uncertainty in the global poverty estimates in a “total-error” approach framework. However, beyond acknowledging the utmost importance of this recommendation, the World Bank, decided not to follow up on this in the foreseeable future (World Bank, 2016).

What is wrong?

A thought experiment can be telling of what is basically wrong with the method used by the World Bank to track global poverty. Many national statistical authorities across the world are working meticulously in order to improve their methods to capture poverty within their jurisdiction. One such development is to tailor the poverty lines they are using across household types in terms of composition, and across geographical regions in terms of price levels. This goes in the direction of tailoring the reference poverty line, which is calculated from first principles, according to the socio-economic realities of the household under examination. This is a process within the spirit of the Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach, which is arguably the most accepted reference theory on poverty conceptualization and measurement that we have.

The dollar-a-day method, on the contrary, does the exact opposite, by building a one-size fits all poverty line (literally, i.e. every person on the planet), which in the last two updates has moved towards separate poverty lines across large groups of countries). The method assumes that one monetary value is able to reflect purchasing power differences across all individual households all over the world.

[M]easurement of global poverty appears to be a domain where institutional inertia and pristine methodological recommendations tend to clash.

There are two reasons for why this is a heroic assumption. On the one hand, the International Comparison Program producing the (so-called purchasing power parity or PPP) exchange rates that try to correct for purchasing power differences across countries, does not have this kind of mandate. Its efforts focus upon relating economies in terms of GDP, and the representative (i.e. average) household in terms of consumption. On the other hand, it has never been demonstrated that a particular dollar value (in PPP terms or otherwise) allows for achieving comparable living standards across countries. The opposite has been shown instead, at least in terms of subsistence poverty (Moatsos, 2016).

However, an additional reason takes priority in explaining the problem. The vast variability in the monetary value of the underlying national poverty lines used in producing the dollar-a-day poverty lines is key in making the method unstable and imprecise. 1For instance, the relative standard deviation across the national poverty lines underlying the current $3/day international poverty line is higher than 50%.

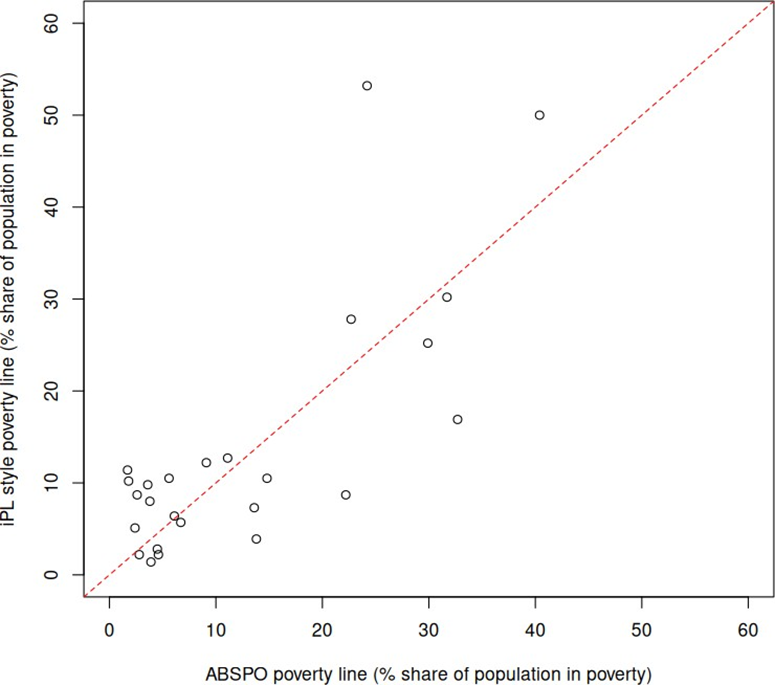

Recent research by the European Commission’s Joint Research Center (Menyhert et al., 2025; Menyhert, 2025) has shown that comparable poverty lines across EU member states that achieve comparable living standards vary considerably (in PPP terms). It can be easily shown (Figure 1) that the results would differ starkly per country should we use a single European poverty line instead, following the dollar-a-day method’s core idea. Figure 1 shows how large the differences are in terms of the actual country specific poverty line estimated by the EU’s Measuring and monitoring absolute poverty (ABSPO) project, against an iPL style poverty line across the entire group (such line has a value of $21.82/day in 2021 PPP dollars).

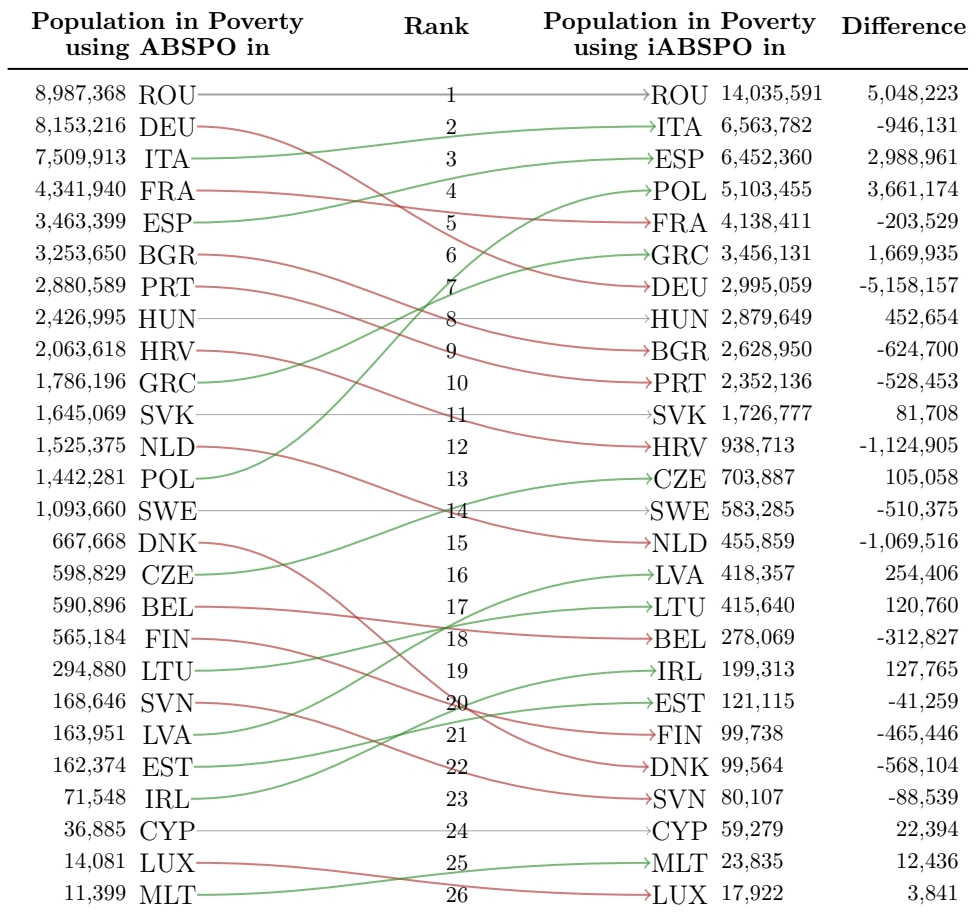

Figure 2 shows the differences in more detail. It illustrates both the impact of the dollar-a-day method on the ranking of the countries in terms of its population living in poverty, and the difference between the two estimates. Some countries see the population living in poverty change by a substantial percentage (e.g. -82.3% for Finland, -53% for Belgium, +56.4% for Romania) or a large absolute number (e.g Romania, Italy, Spain). On average, the absolute difference between the two estimates is slightly larger than 1 million people. In terms of poverty rates, the average difference is just a bit shy of 7 percentile points (while the average estimate is just 15%).

Instrumentally, the underlying poverty lines I borrow from Menyhert (2025) for the figures have been produced with a strictly comparable methodology across all countries considered. This is far from true for the underlying poverty lines used to define the international poverty line of the dollar-a-day method. National Statistical Offices around the world decide differently on various methodological aspects (nutrient targets, reference population, spatial price index, differentiation per household structure, etc.) which makes the national poverty lines inherently incomparable. 2Otherwise, one would quite reasonably assume that the United Nations would be using those directly to gather intelligence for the level of global poverty instead of using any other method, including that of the World Bank.

Not being “paternalistic and disrespectful” 3Quote from the “Cover Note to the Report of the Commission on Global Poverty” The World Bank (2016). Unfortunately now the page on the World Bank website containing this letter gives a ”Page Not Found 404 Error”, though the page is referred to f here as well: World Bank’s Poverty Commission Releases Report on How to Better Measure and Monitor Global Poverty, and the same from the Commission on Global Poverty report page. However, it is still accessible via the Wayback Machine.

The World Bank in defending its choice of not abiding by the recommendation of the World Bank Commission on Global Poverty to incorporate a cost-of-basic-needs framework as a supplementary indicator resorted to arguing that it is not their place to tell countries around the world how they should be measuring poverty (World Bank, 2016). The statistical apparatus behind the dollar-a-day approach simply tries to create a summarizing mirror of the world living in poverty, using only the given national poverty lines as defined by each country. However, this mirror is skewing poverty in a number of ways (some of them discussed above) such that it is hard to defend as not telling, possibly in a not very respectful way, a very different story than the one told by each national poverty line within their own countries. The World Bank instead of opting for (a long overdue) well-specified definition of poverty based on an existing framework, devised its own to suit the aforementioned end goal, of not being paternalistic and telling countries how to define poverty.

Given the methodological inconsistencies in international and intertemporal comparability, no country should base its poverty policies or the appreciation of the efficacy of those policies using the international poverty line.

It is an understandable end goal from a political perspective, but it evidently comes at a very high cost. It is hard to defend it given the large differences between the poverty statistics produced by the national poverty lines and those produced by the international poverty line (Moatsos and Lazopoulos, 2024). It flips the objective from keeping constant what really matters -- the number of people living in conditions of poverty -- as it is an anthropometric indicator, to keeping a poverty line somewhat fixed.

For India, the latest number available at the World Bank “World Development Indicators” repository is from 2011 at 21.9%. For that year, and using the international poverty line from the 2011 PPP vintage the World Bank estimates a poverty rate of 22.83%, using the 2017 PPP vintage the World Bank estimates 16.22%, and using the 2021 PPP vintage the World Bank estimates that 27.12% of the population in India is living in conditions of poverty, all for 2011. As it has been noted in the literature, nothing in the conditions of poverty in India motivates those changes. The on-the-ground experience of the poor did not rise or fall in 2011 depending on the PPP vintage used by the World Bank to monitor poverty.

Interestingly, India seems to be a counter-acting force upon the shooting-up of global poverty statistics due to the new 2021 PPP compliant international poverty line apparatus. Foster et al. (2025) report that for 2021 the overall impact on global poverty of India due to the new methodology was a net reduction by 77 million people. This was the result of two effects that took place for India, one is the increased consumption as recorded in the latest survey data, reducing poverty by 125 million people which has spiralled into a large debate on the underlying methodological choice (see Himanshu (2025)), and the other is the introduction of new PPPs for 2021 that increased poverty by 48 million (against the 2017 PPPs). Should the old version of the Indian household surveys for capturing consumption have been used, the impact of the new global poverty apparatus would have been closer to the unprecedented jump in global poverty statistics of the 2005 PPP vintage (400 million people were then added in global poverty accounting; see Chen and Ravallion (2010)). Presumably the two are unrelated.

What can be done?

Back in 2016, the World Commission on Global Poverty recommended a cost of basic needs framework to operate as a supporting indicator for global poverty measurement in official capacity. The internationally ratified framework of the UN’s Copenhagen Declaration could operate for setting the overarching principles guiding such an application. It is compatible with the framework that it is being used anyway by National Statistical Offices across low- and lower-middle income countries, and many others, to measure their national poverty levels. Methodologically, it is the nearest and most familiar way to draw comparable statistics across the world, and similar to what the recent JRC project did for the European Commission. It has also been favoured by the 2016 World Commission as an accompanying or supplementary indicator for tracking global poverty.

Should international institutions choose not to be “paternalistic and disrespectful” to countries around the world within this framework, they can always provide a pallet of options for countries to choose from , or a more general framework that would abide by all the recommendations set forth by the World Commission on Global Poverty (Atkinson, 2016). 4For a detailed commentary see Moatsos (2018).

The World Bank is doing tremendous work assembling and curating the necessary data for making global poverty measurement possible. The criticism above specifically targets the method of translating those fascinating data into an estimate of global poverty. Still, given the methodological inconsistencies in international and intertemporal comparability, no country should base its poverty policies or the appreciation of the efficacy of those policies using the international poverty line.

Michailis Moatsos is an assistant professor at Maastricht University, and a postdoctoral fellow at King's College London working on global poverty (UKRI/EPSRC Grant Ref: EP/X021149/1 evaluated/awarded as a Marie Curie postdoctoral fellowship)