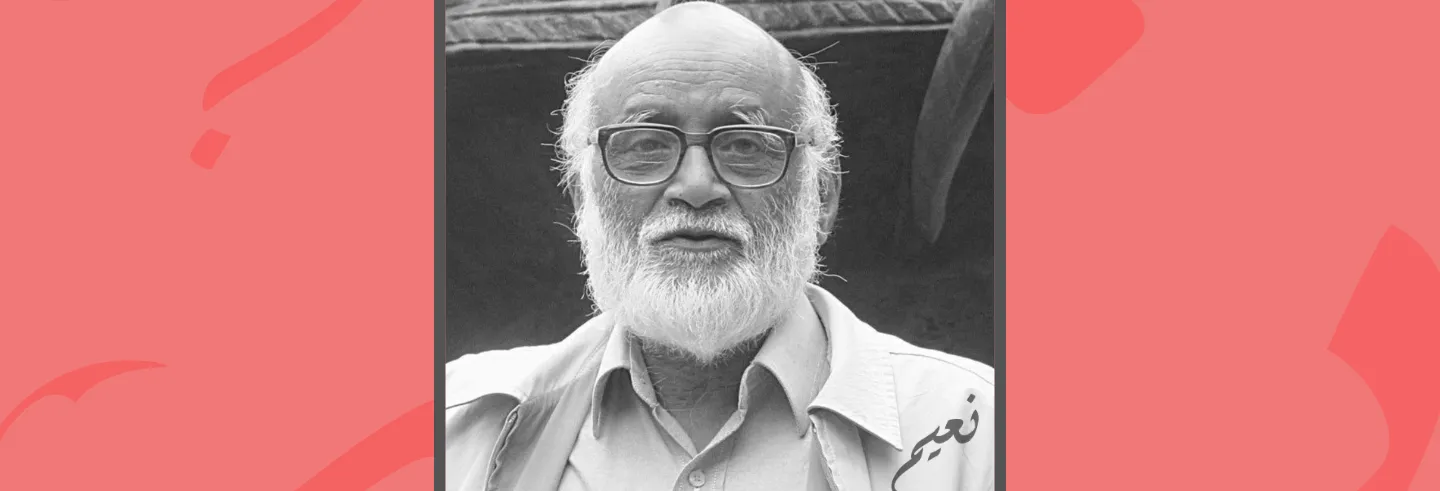

Goodbye Professor Naim

By Vidya Rao

Re-reading, now, his essay on ‘The Art of the Urdu Marsiya’, I realise once more what a wonderful teacher CM Naim must have been. I, sadly, never had the privilege of being his student. But, then to have known him briefly, even if only as an editor—that was privilege enough.

But this essay, as all his writings— I see again how systematically and with such clarity Naim Sahab takes his reader through a maze of unfamiliar terms and concepts! How clearly he explains each idea and the underlying cultural universe held within each word. We, the readers are guided gently, yet rigorously through the complexity, even unfamiliarity, of the world of the marsiya, to an understanding and appreciation of this little-known cultural form in its context.

Professor CM Naim’s passing earlier this month, on the 9 July 2025, brings to an end a world of a certain kind of meticulous scholarship, which could yet connect academic discourse with everyday events and concerns. His was a scholarship that was inclusive—you didn’t have to be an academic or scholar to read and understand and appreciate his ideas. In this he was the archetypal Teacher, including each student, each reader in his work. And more, his work brought to us a world of generosity, graciousness and a refined adab, along with a commitment to secularism that could co-exist with a deep commitment to faith.

Born in 1936 in Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh, educated at Lucknow, Pune and then Berkeley, Professor Naim’s illustrious career spanned many worlds. He taught in universities across the United States and India, eventually, in 1961, finding his home in Chicago’s Department of South Asian Languages and Civilisations. He was Chair of the Department from 1985 to 1991, then Professor Emeritus till the time of his passing. During this time he was also Visiting Professor at Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia (2003) and National Fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, Shimla (2009), and before all this, during 1971-72, was Associate Professor at Aligarh Muslim University.

His was a scholarship that was inclusive—you didn’t have to be an academic or scholar to read and understand and appreciate his ideas. In this he was the archetypal Teacher, including each student, each reader in his work.

His interests and his writings ranged from Urdu literature and language, to Hindi, Persian, Arabic writings, to the arts, to politics, history and so much more. He was perhaps one of the first scholars to look at language in its social and cultural contexts. His writings included scholarly books and papers, and shorter essays; every one of his writings was accessible to the non-academic reader, while never diluting the substance and import of what he had to say.

Professor Naim’s works are essential readings for anyone interested in the world of Urdu, especially in North India. But the import of his writings went far beyond he world of language studies. I am thinking now of his 2013 essay on Hasrat Mohani. Titled ‘The Maulana who loved Krishna’ and published in the Economic and Political Weekly, this brief, but extremely important essay traces for us the work of this extraordinary man who was at once a revolutionary Communist and devout Muslim, exquisite ghazal-sara, who also loved and composed bhakti-laden poetry to Krishna. Hasrat Mohani undertook the Hajj pilgrimage no less than 11 times, yet was invariably also at Mathura to celebrate Janmashtami. Professor Naim’s full length book on Hasrat Mohani, whom he describes as a maverick, is much awaited. The essay and the book evoke for us, and bring us to faith in a world where we can be both-and, never either/or. He gives us a world where identities need not be rigid water-tight boxes, but, a sincerely and deeply understood vastness that can easily, lyrically, encompass what the world now thinks of as eternally opposed contradictions.

Yet another book that is significant for anyone interested in Urdu poetry and culture and cultural history is his translation of Zikr-e-Mir, the Farsi autobiography of the 18th century poet Mir Taqi Mir. But these are only two of the many essays and books he has left for us.

Professor Naim’s contribution to the field of Urdu language and literature studies is immeasurable. He was Founding Editor of the journals Annual of Urdu Studies and also of Mahfil (now called Journal of South Asian Literature). He wrote the definitive textbook in English on Urdu pedagogy and authored books such as the Urdu Reader: An Introduction to Urdu, the two-volume Conversational Hindi-Urdu and Readings in Urdu Prose and Poetry. Other books include Iqbal, Jinnah and Pakistan: The Vision and the Reality; Two Days in Palestine; The Hijab and I: Ambiguities of Heritage; A Killing in Ferozewala; and The Muslim League in Barabanki. He translated from both Urdu and Hindi into English—Vibhuiti Narain Rai’s Curfew in the City and Harishankar Parsai’s Inspector Matadeen on the Moon, as well as Qurratulain Hyder’s short stories and a novella under the title A Season of Betrayals. And of course, there is his translation from the Persian of Zikr-e-Mir. Then there were his innumerable essays published in journals, some of which were collected and published in a book called Urdu Texts and Contexts.

There are some people who by their prodigious learning, their wisdom, their generosity in sharing that wisdom and the beauty of their world, embody what it is to be a guru, a guide and mentor.

It is my eternal regret that I never met Professor Naim. But I did have the privilege of working with him as Orient BlackSwan’s commissioning editor for two of his books. The first, A Most Noble Life, is a translation by Professor Naim of Hayat-e-Ashraf, a biography of Ashrafunissa Begum by her younger friend and colleague Muhammadi Begum. Professor Naim’s detailed Introduction to this seemingly simple, certainly brief, biography brings to the reader’s attention issues around education among Muslim women in early 20th century north India, the world of female friendships and mentorship and indeed the complex negotiations women managed between social mores and their commitment to women’s literacy and education. The second book was his brilliant Urdu Crime Fiction, perhaps the first full study of this subject. It unravels how Urdu writers responded to the new genre of crime fiction to create a highly popular genre, jasusi adab, of books, often also serialised in magazines. And I doubt there is a single scholar working in the fields of Urdu, Hindi and Persian studies and related fields who has not received guidance from Professor Naim.

For me, as his editor, there was the honour—and joy-- of working with a writer of his stature, vast knowledge, and graciousness. Equally, of working with texts that were meticulously researched and written but were yet so accessible for the non-academic reader. And there was the honour and joy of just being in his presence—even if only on email. Professor Naim was always gracious, always warm, responding to each and every query with patience and care. To be a small part of his world meant that we—my younger colleague, Moyna Mazumdar and I—received from him from time to time his own writings on issues affecting the world, the writings and speeches of others, and even music clips. Book editors are often invisible, indeed must be invisible presences in the work of creating a book from a manuscript. Yet Professor Naim never failed to acknowledge our absent presence, to listen to every concern, to give every query his attention.

But there is more! His graciousness ensured that we became a small part of his world. Every New Year we would receive greetings from him, a lovely e-card, one that opened up to a charming picture and a piece of music. And on a completely non-publishing-related note, he would often send me clips of music that he had heard and enjoyed and thought I might like too. My official letters to him would often end on a personal note—of music I had heard, or about the beauty of Delhi’s basant-ritu with its flowering kachnar, its koel ki pukaar, of the delight of spotting and bringing home the first langda mangoes of the season, of the joy of the first monsoon rains (flooded roads notwithstanding!)…..

There are some people who by their prodigious learning, their wisdom, their generosity in sharing that wisdom and the beauty of their world, embody what it is to be a guru, a guide and mentor. In the best sense of the word, a guru is that wise guide who has studied much and seen more, who shares his/her wisdom generously, and who is both patient and exacting. In the few years that I was fortunate to know Professor Naim, albeit only via email, I found myself thinking of him as a respected scholar, an eminent author, but also as a teacher, a guru from whom I was privileged to learn so much.

Gurus are teachers and guides. But they also create for us a family, a community of people we may meet or not, but with whom, because we are now guru-bandhu, we are connected by the deep bond of the quest for true knowledge and indeed of love and respect for the teacher. This community of guru-bandhus is another gift that Professor Naim bestowed on me. He introduced me to his student, a young and brilliant scholar, Shefali Jha, who is now a dear friend, and whose own book is forthcoming from Orient Blackswan.

Professor Naim left us on Guru Purnima. The world has lost a great scholar and a fine human being. For me, his passing feels as if I have lost a deeply respected and indeed much loved guru. But, thinking of his work, his writings, his staunch commitment to secular ideals, to peace and justice, I am also grateful that, if only briefly, if only over email, I was honoured to know this wonderful human being.

Vidya Rao is a singer and writer and also works as an editor with the publishers Orient Blackswan.

In Naim Sahab’s Class

By Shefali Jha

A moving tribute to C.M. Naim, celebrating his warmth, wit, and passion for Urdu poetry. Remembered for his kindness, intellectual rigour, and belief in learning through community and conversation, Naim sahab inspired generations as a devoted teacher, literary maverick, and steadfast champion of Urdu literature.

I almost did not take Naim sahab’s advanced Urdu reading course in the Winter of 2010 at the University of Chicago. Being certain my Urdu was nowhere near good enough to sit in his class, where he would read the extraordinary elegiac poetry of Mir Anis with us, it was on the persuasion of more sensible friends that I found myself in the office where four or five of us would eventually spend hours of the week immersing ourselves in the jalal and jamal of Imam Hussain, in the history of the Urdu marsiya, and the Awadh traditions of listening, recitation, and mourning the genre brings alive.

I could say we were in awe of Naim sahab’s reputation as a scholar and non-sufferer of fools, but that would only be half true. We were plain scared, graduate students on the verge of candidacy, having weathered many a Chicago seminar and taught a few undergraduate classes ourselves. After all, we had been at conferences where his voice would call out from the back of the room after a couple of inexcusably long papers, “Madam Chairperson, could you tell the audience how much time each presenter is allotted?” Or telling off a visiting scholar for their pronunciation, “First, please note that it’s Mus-lim, not Muz-lam.”

…Naim sahab introduced young students to his older students, colleagues, and fellow travellers, told us off for not asking enough questions, debated everything from politics to the latest books to the traditions of the university.

So it was that before every class—for the first month anyway—we re-read every line we would have to read aloud in class for the Judgement of the World, meeting in the Regenstein Library’s basement to consult the weighty volumes of the Farhang-e-Asafiyya to puzzle our way through an array of weapons, implements, pieces of clothing, planets, stars, animals, and sonorous terms for heroism and villainy out of which Anis (later we would read Mirza Dabir, that other great master of the marsiya) made some of the most moving poetry ever written.

Looking back, it became clearer that Naim sahab almost instantly put us at our ease, with his kindness and humour, and perhaps most of all by his own immersion in the poetry, which he recited aloud with such a range of performative mastery that we were both diminished—how could anyone ever hope to read that way?—and elevated by the listening. It was one of those classes where one could feel the limits of Chicago’s prized Socratic method on the skin—we wished Naim sahab would do all the reading, because that was the education we had come for, even though our halting, stuttering Urdu reading followed by his commentary was ... productive.

In the event, we graduated to being invited to his beautiful apartment for tea and the occasional meal. The warm gravity of that place is hard to overstate. There Naim sahab introduced young students to his older students, colleagues, and fellow travellers, told us off for not asking enough questions, debated everything from politics to the latest books to the traditions of the university, particularly of the department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations. We would invariably try to outstay our welcome, to turn an invitation for lunch or tea into an early supper—to no avail.

Naim sahab was an impeccable host and what they call mahfil-parast, but he also loved his time with his own books, music, and work. He wrote every day, and read several newspapers in Urdu and English from across the world; he read forwards and forwarded them, he excerpted the ironic, tragic, the farcical, and the beautiful from his reading and shared them with a virtual reading public over email.

He made time for Hindi movies, for his flower-beds and his wild garlic plants, to walk around Chicago’s Hyde Park, enjoy the spring flowers and new public art, pop into Powell’s bookstore, and to connect the appropriate person with a book that needed reviewing or a publisher he happened to know. He made time to look at draft translations and papers and offer detailed comments, and he made time to scold.

All of this was possible because he had a routine that he guarded jealously, which no grad-student-come-lately was going to disrupt. Towards the end of my time at Chicago, I think we dawdled after tea because we secretly cherished the rite of being thrown out with Naim sahab’s imperious “Accha chaliye, ab aap log tashrif le jaiye.”

One of the biggest compliments I had from him after a workshop paper was, “Bhai, this was very disappointing. I understood everything; I think you’ll need to rewrite it.”

If he was around to read these words, he would undoubtedly cross out several adjectives and adverbs, possibly to the accompaniment of deep and audible sighs. Naim sahab had an aristocratic contempt for excess, strange as that may sound. The slightest exaggeration, mixed metaphors shading into cliché—sometimes even simple metaphors—and his impulse would be to bring it back to earth.

“Naim sahab, aap to Eid ka chand ho gaye,” I said to him once, trying out a favourite Urdu turn of phrase when I saw him at a talk after a long time. “Hmm … Qurbani wali Eid ka ya Meethi Eid ka, ye bhi bata dijiye, Begum sahab,” with a smile and a glint in his eye. He was also a stickler for detail—names, dates, words, events, his own thought process. To recording all of these he brought the same love of proportion and exactitude.

It was his allergy to excess that was at the heart of his suspicion of “theory”. I remember trying to extract a theory of translation—or several—by discussing aspects of his work on the Zikr-e-Mir with him. He wasn’t having any of it—you read the text, you try different things, you keep at it until it sounds right. What is the point of all this theory you anthropology people do, he would say. You only want people to think you’re doing something profound. One of the biggest compliments I had from him after a workshop paper was, “Bhai, this was very disappointing. I understood everything; I think you’ll need to rewrite it.”

All of us who knew him and had the privilege of sitting in his class—literally or figuratively—recognised in Naim sahab the last of the mavericks he loved so much. He had a special eye for the figure, the gesture or the work that stood out, that took on the world without being weighed down by the act; something or someone that disrupted the drive towards foreclosure—Ghalib, Hasrat Mohani, Sir Syed, Tirath Ram Ferozepuri, Ashrafunnisa Begum, Muhammadi Begum.

It is the quality he captured in that imaginative tour de force of cultural history “Individualism within Conformity: A Brief History of Waz’dari in Delhi and Lucknow” (2011). Waz’dari, he wrote, was driven by the “desire … to get away from the uniformities imposed by some overarching, impersonal adab while remaining true to some personal adab of one’s own choosing” (38). There will always be much more to say, but perhaps it is time to heed Naim sahab’s voice in my head and stop, because he said it best.

Shefali Jha is an anthropologist who teaches humanities and social sciences at the Dhirubhai Ambani University (formerly DA-IICT), Gandhinagar, Gujarat.