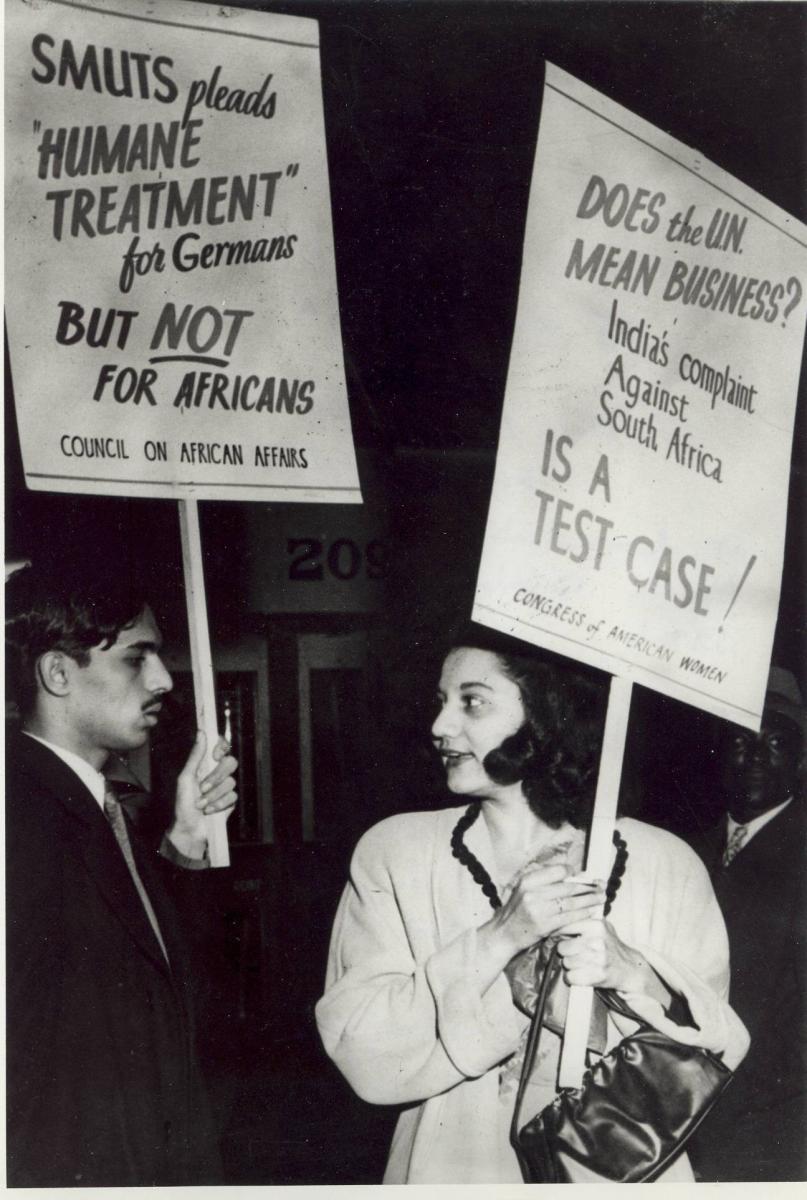

In late 1946, two iconic leaders of the African-American community, Paul Robeson and W. E. B. Du Bois, organised a protest in front of the South African consulate in New York. The white supremacist South African government had enacted legislation – the “Ghetto Act” – to restrict the property rights of Indians. This led to the first mass protest by Indians in South Africa since the departure of Gandhi from its shores. The New York picket line was assembled to protest against the repression of the Indian passive resistance campaign and a strike by mine workers. Amongst the protestors were a group of young Indians brought there by a student at New York University, E. S. Reddy.

While he was literally fresh off the boat, having arrived in America earlier that year, it is unsurprising that Reddy would join the protest. He had come of age in a period when India's long struggle for freedom was about to bear fruit. Moreover, there was a sense of affinity with South Africa's Indians owing to the Gandhi connection. But what was altogether exceptional was that from that first protest onwards, Reddy would dedicate his life to fight for the end of racial discrimination in South Africa. As the African National Congress recalled in its statement on his passing on 1 November 2020 in Cambridge, USA, Reddy had stayed steadfast to his belief: “I cannot feel free, as an Indian, until South Africa is free of apartheid.”

Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy was born on 1 July 1924 in the village of Pallaprolu, near Nellore in present-day Andhra Pradesh. With the family in debt, his father had to seek a formal job and they moved to Gudur. Growing up with four brothers and a sister, Reddy graduated with a BA from Madras Christian College in 1943. Like many others, he was eager to travel to the west for his education but did not wish to go to the country that had colonized India, the United Kingdom. Once the Second World War ended, he took the first available ship and arrived in America in March 1946.

He had intended to go to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to study chemical engineering, but owing to the dislocation of the times arrived rather late for the term. Thereupon he changed his plans and enrolled for a Masters in International Relations at New York University. Upon graduating in 1948, Reddy moved to Columbia University to pursue a PhD in Public Administration. But by this time he was utterly broke and could not continue his studies any further. In 1949 he obtained a position at the recently established United Nations Organization. A year later he was married to the Turkish scholar Nilufer Mizanoglu with whom he was to have two daughters (some details are available here).

All through the era of the South African struggle, India had played a critical role. This was owed to the legacy of both Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.

1946 was a significant year. A catastrophic global war had just ended and many countries were counting their losses and picking up the pieces. As Victor Sebestyen shows in his global history 1946: The Making of the Modern World, the decisions taken in that year have profoundly shaped our contemporary world. Sebestyen's narrative is sweeping but there is a yawning gap as regards the events in the African continent. Many Asian countries – notably India and China – were to soon become free or be decisively transformed. But Africa continued to be in the grip of the twin curses of the 20th century – colonialism and racism. However, change was afoot and the mass protests of 1946-48 in South Africa were to inaugurate a long period of struggle that ended with the release of Nelson Mandela in 1991 and the formation of that nation's first democratically elected government in 1994. Reddy played a fundamental role in the global campaign of solidarity that helped put an end to apartheid.

All through the era of the South African struggle, India had played a critical role. This was owed to the legacy of both Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. In 1946 the Ghetto Act and the subsequent crackdown against protestors in South Africa had aroused strong passions in this country. Amidst the turmoil of the period, the strength of popular sentiment forced the Viceroy, Archibald Wavell, to place a trade embargo against South Africa. Subsequently the interim government of Nehru took a more active position, with action moving to the United Nations. With both Gandhi and Nehru deeply concerned about the ominous segregationist developments in South Africa, India played a key role in the United Nations (UN) to make South Africa's actions a matter of global scrutiny (See Bhagavan 2013).

The UN was never truly representative and by 1950 America's Cold War mentality and McCarthyism had permeated the organisation. Reddy found “the atmosphere to be oppressive”, but his job allowed him to read up on South Africa on “company time”. He recognised that his NYU education in international relations was tainted by racist beliefs and a hatred of nationalism in the colonies. Reddy felt he was saved from taking offence by his sense of humour, but knew that he had to jettison such baggage and “think with my blood”, i.e. in terms of Indian nationalism that included solidarity with other oppressed peoples.

Even before E. S. Reddy left India, he had read some pamphlets on the problems in South Africa which triggered his interest and a sense of commitment.

Like many of his generation, Reddy respected Gandhi but it was Nehru's socialist and internationalist outlook that he found more appealing. Even before he left India, he had read some pamphlets on the problems in South Africa which triggered his interest and a sense of commitment. Now he felt a personal responsibility towards aiding African countries in their struggle against colonialism and racism.

In the meanwhile, the brutal oppression of the South African regime was resisted by the Defiance Campaign of 1952. This was the first large-scale protest carried out jointly by the South African Indian Congress and the African National Congress wherein activists defied the apartheid laws that placed many restrictions, including the ability to move freely without permits. As Reddy was to later write, the Defiance campaign “shattered the stupid racist myth that the African and black people were somehow incapable of an organised and disciplined nonviolent resistance.” At the UN, he ran afoul of his boss for agreeing with the Indian government's argument that the apartheid laws were not a domestic matter as South Africa insisted, but a gross violation of the UN Charter. He was shunted out to a different desk but when a commission on racism in South Africa was established, Reddy was brought in owing to his already well-developed understanding of that country and its problems.

Reddy toiled away at his job preparing reports and organising meetings, with little impact. With the main western powers backing South Africa, Reddy reckoned that the challenge to apartheid could not gain traction until Africa was decolonised and its free nations could participate in the UN on their own terms. A 1962 resolution called for the ending of diplomatic ties with South Africa and, thanks to Reddy's effective lobbying, the appointment of a full time body which came to be known as the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid (see Konieczna 2019). He became the Principal Secretary of this committee and served in this and related positions till his retirement in 1984 with the rank of Assistant Secretary-General.

It is generally believed that the widespread international pressure helped prevent the death sentence being imposed [in 1963] on Mandela and his comrades.

Soon after its formation, the Committee Against Apartheid faced its first major crisis. In 1963, the South African regime began the trial of Nelson Mandela and his colleagues for acts of sabotage and attempting to overthrow the government. The Rivonia trial became a global cause celebre as it was feared that the defendants would be awarded the death sentence. In an unprecedented move, the UN General Assembly almost unanimously adopted a resolution calling for the end of the trial and the release of all those imprisoned for their opposition to apartheid. The resolution was supported by 106 countries against one opposing vote – that of South Africa. That resolution was drafted by Reddy who worked alongside African diplomats and successfully convinced a handful of reluctant western nations to support the motion.

It is generally believed that the widespread international pressure helped prevent the death sentence being imposed on Mandela and his comrades. Rivonia came to be known as “the trial that changed South Africa” and Nelson Mandela became an international hero for his fearless statement in court that a democratic and free South Africa was “an ideal for which I am prepared to die”.

At the UN the major western powers boycotted the Committee Against Apartheid and it was expected that their intransigence would make the committee a worthless endeavour. But Reddy was not to be deterred and he hunkered down for the long haul in a tricky and hostile work environment. Years later he noted that in the event, “the Committee proved to be very influential and effective.” What he left out was the fact that this effectiveness of the committee was owed overwhelmingly to his own exertions. Reddy was soft-spoken and polite, but he could not be accused of false modesty. He recalled that he did not know of any other UN official who worked on “an issue with equal determination and conviction”. Over two decades he worked seven days a week, put in 70-80 hours of work and took no holidays or vacations.

On occasion Reddy had doubts about the value of his labours. But he was reassured by his vast network of friends in the various African liberation struggles who recognised the significance of his work at the UN.

Since South Africa continued to command the support of permanent members of the Security Council such as the USA and the United Kingdom, Reddy worked on moving the action to other fora, both within and outside the UN. He was innovative in getting NGOs and individuals involved in the struggle, including ANC leaders, to depose in front of the Committee which kept the focus on the cause. Throughout his tenure, Reddy also produced an endless stream of reports for use by campaigners. When he visited the offices of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement, Reddy noted that a table had only three legs. The role of the missing leg was served by a stack of old UN reports he had written!

For a long period, these efforts had little impact. On occasion Reddy had doubts about the value of his labours. But he was reassured by his vast network of friends in the various African liberation struggles who recognised the significance of his work at the UN. While he worked primarily on South Africa, it must be remembered that the liberation of all of Africa was what he desired. Later in life he commented that “With the redemption of Africa, a shameful era of human history — of imperialism and colonial domination will soon come to an end, and humanity would have confronted what the Pan African Movement defined in 1900 as the problem of the twentieth century, the problem of the 'colour line'.”

With not much progress on the question of apartheid at the UN, Reddy recognised the need to build pressure from the outside. Decades later when a scholar interviewed anti-apartheid activists, they all independently pointed out Reddy's influential role in this regard. He was that rarity, an “activist public official” (see Thorn 2006). He conducted a number of conferences across the world to raise awareness and build a network of solidarity across borders on the question of apartheid. He also worked with smaller European nations that did not share in the political positions and colonial attitudes of the major powers. As a result he developed a close relationship with the Swedish Prime Minister, Olof Palme, who emerged as an influential western opponent of apartheid. Some believe that Palme's assassination in 1986 was at the behest of the South African regime.

He also became a friend and supporter of the President of the ANC, the legendary Oliver Tambo, who had gone into exile to build global support against apartheid. In 1965, Reddy shrewdly advised Tambo that the latter should not talk of the South African question as a colonial problem but pose it as a racial one. Reddy argued that since South Africa was not a colony, talking about apartheid in terms of colonialism would harden the attitude of European powers such as Netherlands who would interpret it as implying that the ANC intended to expel the white population out of South Africa. Incidentally, Tambo was able to travel freely while in exile and carry out his extraordinary work in mobilising world opinion thanks to an Indian passport given to him by Nehru's government.

Following Reddy's suggestion to the then foreign minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in 1979 the Indian government bestowed upon Mandela the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding.

The South African government was spending some $15 million annually for propaganda that demonised the ANC and its leadership. It was necessary to counter this well-oiled publicity machinery by building a groundswell of popular support. While many Western governments were duplicitous on apartheid, in an age of mass democracy they were not immune to public opinion in their own countries. The global sports boycott of South Africa was one such successful endeavour, in which Reddy played a part.

Meanwhile, after a conversation with the ANC activist in exile Mac Maharaj, he proposed to a network of activist and civic groups that Nelson Mandela's 60th birthday (18 July 1978) be celebrated as a public event. The campaign resulted in more than ten thousand letters of greetings and solidarity being sent to Mandela and his wife Winnie, both in different prisons, and major public events such as the Free Mandela concerts in Britain. 'Mandela Fever' helped transform the widespread scepticism about the man to one of admiration and even adulation. Following Reddy's suggestion to the then foreign minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in 1979 the Indian government bestowed upon Mandela the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding. This was the first such significant honour for Mandela and opened the doors for similar awards that highlighted his imprisonment and helped change public perception.

During his career at the UN, Reddy brought an appetite for hard work, a prodigious memory and an unerring command of facts to bear on the problem of apartheid.

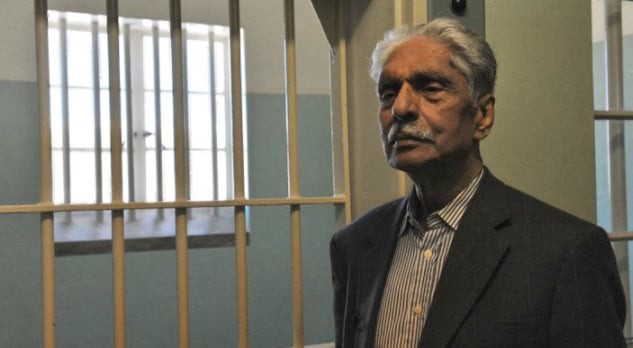

Diplomacy and lobbying are the unglamourous aspects of aiding a revolutionary struggle. The enormous burden and costs of the struggle against apartheid were borne by South Africans themselves. But the decades of global solidarity were crucial in making that evil regime untenable. In this transformation, Reddy played a pivotal, indeed indispensable role. In 2013 the South African government honoured him with an award named after his friend of long years, the Order of the Companions of Oliver Tambo. Reddy could look back in satisfaction that since reading his first pamphlet on South Africa in 1943, he had been an unfailing champion of freedom in South Africa and the African continent itself.

During his career at the UN, Reddy brought an appetite for hard work, a prodigious memory and an unerring command of facts to bear on the problem of apartheid. Upon retirement in 1984, his irrepressible energies and commitment found other channels of expression. While this included documenting the South African struggle that he knew so well and was part of, Reddy also returned to the man who had been a quiet presence in his life all along—Mahatma Gandhi. As part of our freedom struggle, Reddy's father had spent three months in prison in 1941 and his mother had donated her jewels to Gandhi's campaign against untouchability. The eight-year-old Reddy first saw the Mahatma on the 20th of December 1933 at a public meeting in Gudur and went around the meeting with an upturned Gandhi cap to collect a few pies for the cause.

While he lived and worked for more than seven decades in the US, Reddy remained a proud holder of an Indian passport.

With his extraordinary capacity for industry and a nose for ferreting out rare documents, for many decades Reddy was a vital figure in the study of Gandhi's life. He single-handedly produced a very large body of essays and collections that reflected on different aspects of the Mahatma's life and also highlighted novel sources of understanding. For many students of Gandhi's life, this writer included, he was a vital guide that one could always rely upon. He was unusual in his scrupulous attention to detail, an ability to work with a large number of collaborators and the generosity with which he gave away the fruits of his research findings for others to use.

In his New Year's greetings for 2016, into his tenth decade, Reddy told his friends: “I look forward to a busy year ahead, as I am still able to do research, edit and write.”

While he lived and worked for more than seven decades in the US, Reddy remained a proud holder of an Indian passport. His life was shaped by the values of an India that had non-violently fought for its freedom, but also saw its fate as inextricably bound up with that of other oppressed peoples around the world. During the freedom struggle, India had the services of a number of Britons who gave themselves to a cause they believed to be correct, the end of Empire. C. F. Andrews, Reginald Reynolds, Agatha Harrison, Muriel Lester, Madeleine Slade (Mira Behn) and Fenner Brockway are a few such names. In going beyond the confines of one's own nationalism to embrace the righteous causes of the world as one's own, E. S. Reddy is a rare Indian name in this vein.

The world that Reddy has departed from is very different from the one he had entered in 1924. European colonialism is a thing of the rather distant past, but peoples and nations across the planet grapple with the problems of inequality and injustice amplified in our contemporary times. India seems to be on the edge of a precipice where it is about to fully shed the legacy of its freedom struggle. In South Africa, the ANC is a pale shadow of its revolutionary past and mired in all manner of crises of legitimacy. Yet one must never forget that the struggles in these two countries were central to the transformation of the world in the 20th century.

At a time when most societies are turning intolerant, insular and ignorant about the lives of others, the life of Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy offers a lesson in its passion and commitment to democracy, to justice and solidarity across borders and creeds.

The author thanks Ramachandra Guha for his comments on this article.